Sergio García Palacín

Lieutenant Guardia Civil

Head of the Torrelavega Traffic Unit

Cantabria Traffic Department

THE BREACH OF VEHICLE

IMMOBILISATIONS ON INTERURBAN ROADS IN CANTABRIA

THE BREACH OF VEHICLE IMMOBILISATIONS

ON INTERURBAN ROADS IN CANTABRIA

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE BREACH OF IMMOBILISATIONS. 2.1.Sanctions and penalties. 2.2. Statistical analysis of infringements committed on interurban roads in Cantabria (2018/2022). 3. IMMOBILISATION BY THE TRAFFIC UNIT. 3.1. Means used to immobilise vehicles. 4. INTERVIEWS AND SURVEY. Interviews with road safety authorities. Interviews with the heads of the police forces responsible for road safety. Survey of members of the Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil in Cantabria. CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Resumen: Nuestro ordenamiento jurídico en materia de la seguridad vial y de la ordenación del transporte terrestre regula la medida provisional de la inmovilización de un vehículo aplicada por los agentes de la autoridad encargados de la vigilancia del tráfico y del transporte. El quebrantamiento de estas inmovilizaciones supone que en muchas ocasiones se genere un grave riesgo para la seguridad vial al permitir que se continúen cometiendo las infracciones que motivaron la aplicación de la medida, especialmente las relacionadas con el consumo de alcohol o drogas, por su relevancia en la producción de la siniestralidad vial con víctimas mortales. Con el propósito de evitar o minimizar estos quebrantamientos que se producen en las vías interurbanas de Cantabria, es necesario realizar un estudio que incida en la idoneidad de las actuales sanciones y penas asociadas, y en la práctica de las inmovilizaciones de vehículos que realizan los componentes de la Agrupación de Tráfico de la Guardia Civil, desde la perspectiva de la eficacia de sus medios para asegurar la medida provisional y de su regulación interna sobre el procedimiento operativo para aplicarla.

Abstract: Our legal system on road safety and land transport regulation regulates the provisional measure of the immobilization of a vehicle applied by the authority agents in charge of traffic and transport surveillance. The violation of these immobilizations means that in many cases a serious risk is generated for road safety by allowing the violations that motivated the application of the measure to continue being committed, especially those related to the consumption of alcohol or drugs, due to their relevance in the production of road accidents with fatalities. In order to avoid or minimize these violations that occur on the interurban roads of Cantabria, it is necessary to carry out a study that affects the suitability of the current sanctions and associated penalties, and the practice of vehicle immobilizations carried out by the components. of the Traffic Group of the Civil Guard, from the perspective of the effectiveness of its means to ensure the provisional measure and its internal regulation on the operating procedure to apply it.

Palabras clave: Quebrantamiento, inmovilización, seguridad vial, transporte terrestre, siniestralidad vial.

Keywords: Breakdown, immobilization, road safety, land transportation, road accidents.

ABBREVIATIONS

ATGC - Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil.

BOC - Official Gazette of the Civil Guard.

BOE - Official State Gazette.

COTA - Traffic Operations Centre.

CP - Criminal Code

DGT - Directorate General for Traffic.

H - Hypothesis.

LOTT - Law on the Organisation of Land Transport.

LSV - Road Safety Law.

PS - Derivative Question.

RDL - Royal Legislative Decree.

ROTT - Regulation of the Law on the Organisation of Land Transport.

SIGO - Operational Management System (Guardia Civil computer application).

1. INTRODUCTION

As part of the daily services provided by the members of the Traffic Unit of the Civil Guard (ATGC), it is common for a vehicle to be immobilised as a provisional or precautionary measure with a view to preventing specific administrative or criminal offences from being committed, to guarantee road safety and fair competition in the land transport sector or even to protect financial penalties applied to offending citizens who do not reside in Spain.

In Cantabria, agents belonging to the Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil perform these immobilisations of vehicles on interurban roads and breaches of such measures often continue to seriously endanger road safety, leading in some cases to road accidents or reckless driving.

The media coverage of these breaches should also not be overlooked, especially when vehicles are immobilised for alcohol and drug offences and the perpetrators repeatedly commit the same offences, having skipped successive immobilisations.

These circumstances posed the question of whether the current sanctions and penalties reserved for breaches have a sufficient deterrent effect on potential offenders and, in turn, whether the role of enforcement officers in charge of monitoring traffic and road safety should be limited to applying the provisional measure of immobilisation in cases covered by the current legislation, or whether they should go further and try to ensure it in the best possible way to prevent breaches from occurring and the offences that gave rise to the immobilisation from continuing, especially when these offences pose a serious risk to road safety. As a result of these reflections, the idea came about of performing this undertaking as a tool aimed at preventing the breach of vehicle immobilisations on interurban roads in Cantabria, focussing the study on optimising the practice of immobilisations carried out by the ATGC and on the suitability of the sanctions and penalties applied to perpetrators, with a view to establishing the appropriate proposals for improvement, if necessary.

Having defined the problem, this STUDY will focus on the breaches of vehicle immobilisations on interurban roads in Cantabria over the past five years.

The performance of this research work is based on the following question:

§ Can the breach of vehicle immobilisations on interurban roads in Cantabria be avoided or minimised by improving the practice of immobilisations carried out by the ATGC and by increasing the sanctions and penalties applied to perpetrators?

To help resolve this initial question, the following derivative questions arose and were resolved:

- Are there any procedures in the internal regulations of the ATGC for proceeding with vehicle immobilisations?

- Can the effectiveness of the means or mechanisms used by ATGC to immobilise vehicles be improved?

- Should the sanctions and penalties imposed on those responsible for breaches be increased?

In turn, these questions lead to the formulation of the following hypotheses to be addressed in the present study:

- “If there were an operational procedure at the ATGC for performing immobilisations, the number of breaches would be reduced”;

- “If the ATGC were to use more effective means or mechanisms to perform immobilisations, it would be possible to prevent breaches from occurring”;

- “Tougher sanctions and penalties for breaching immobilisations could reduce the risk of them materialising”.

As part of this trial, the study method used consists of the hypothetical-deductive method, in which, based on the analysis and interpretation of the phenomenon studied, we will try to validate or reject, where appropriate, the hypotheses initially put forward, following previously defined lines of research. A qualitative paradigm has also been used, based on the analysis of numerous documents related to the provisional measure of vehicle immobilisation, as well as interviews and surveys performed with people in positions and functions related to road safety.

2. THE BREACH OF IMMOBILISATIONS.

After immobilising a vehicle, the traffic officer expressly orders the driver to refrain from driving it until the causes that led to the immobilisation cease to exist, and in the event of disregarding this order, the immobilisation will be breached. These cases of breaches are not punished in the same way, depending on whether road safety or road transport legislation, or even criminal law, applies to them.

Breaches of immobilisations allow the infringements that led to the immobilisation to continue, with the serious damage that this entails. To assess whether road accidents on interurban roads in Cantabria pose a problem for road safety and for the transport sector, a statistical analysis of the data recorded by the Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil of Cantabria will be undertaken.

2.1. Sanctions and penalties.

Breaching the immobilisation of a vehicle is considered as disobedience to the express order of an officer of the authority. This particular view can be attributed to the fact that when the officer immobilises a vehicle, they expressly warn the driver that they are not allowed to drive until the causes that led to the immobilisation cease to exist, which must also be verified by an officer prior to the lifting of the immobilisation. Failure to comply with this prohibition, without the express authorisation of an officer, would constitute a breach and, consequently, disobedience.

Initially, these breaches were prosecuted under criminal law, with the perpetrators being charged with an alleged misdemeanour for minor disobedience to a police officer, as defined in Article 634 of the Criminal Code (CP) and punishable by a fine of ten to sixty days. This led to numerous court appearances by traffic officers, which was detrimental to the service, as well as overloading the courts.

However, in 2015, two important legislative reforms took place that would overhaul the way in which the breach of immobilisations in the field of road safety were punished: on the one hand, through Organic Law 1/2015, of 30 March, which resulted in a profound reform of the Criminal Code resulting in many offences being decriminalised and others becoming minor offences; and on the other hand, the new Law on Public Safety (Organic Law 4/2015, of 30 March) came into force, which repealed and replaced the previous Law dating to 1992. Among the offences that ceased to be punishable under criminal law and that became administrative offences was minor disobedience to police officers, which was classified as a serious offence under the new Law on Citizen Safety (Article 36.6), punishable by a fine of 601 to 30,000 euros.

Effective this reform, breaches of immobilisations are now sanctioned as an administrative offences, initially processed by the Government Delegations or Subdelegations as offences of disobedience to officers in the exercise of their duties pursuant to the Law on Citizen Safety 4/2015. However, following the entry into force of Royal Legislative Decree (RDL) 6/2015, of 31 October, approving the consolidated text of the Law on Traffic, Circulation of Motor Vehicles and Road Safety, Article 76(j) on 31 January 2016, “not respecting the instructions and orders of the officers responsible for monitoring traffic” is now considered serious offence, whereas in the previous law, the LSV (the now repealed RDL 339/1990) only the action of not respecting the instructions of officers was an offence (Article 65.4(j), with no mentioning the orders of officers. With this new wording, disobedience to traffic officers was included in road safety legislation, making it possible to report the breach of the immobilisation of a vehicle as a serious infringement of Article 76(j), of the LSV, in relation to Article 143(1), of the General Traffic Regulations (RGC), punishable by a fine of 200 euros and the deduction of 4 points from the offender’s driving licence. In 2022, following the entry into force of Law 18/2021, of 20 December, which amended Article 76(j) of RDL 6/2015 of the LSV, changed its current wording as follows: “failure to respect the instructions or orders of the authority responsible for the regulation, organisation, management, monitoring and discipline of traffic, or of its agents", which also includes disobedience in response to the orders of the competent traffic authority.

Following the introduction of this new offence of disobedience to the orders of traffic officers in the LSV, would it be possible to report the breach of an immobilisation related to road safety under the aforementioned Organic Law 4/2015 on the Protection of Public Safety? To answer this question, we must turn to the Public Safety Law itself, in particular, Article 31 thereof, which establishes the corresponding rules and procedures, stating in point 1 that “actions that may be classified according to two or more precepts of this or another Law shall be punished in line with the following rules” and in section a) that “The special provision shall be applied preferably to the general provision”, implying that if the specific offence is included in the traffic legislation, the specific provision must be applied first, with preference to other subsidiary legislation, as in this case would be the Public Safety Law. This legal criteria is also included in point 1 of the first additional provision of Law 39/2015, of 1 October, on the Common Administrative Procedure of the Public Administrations, which regulates specificities by subject matter, establishing that “the administrative procedures regulated in special laws by subject matter that do not require any of the formalities provided for in this Law or regulate additional or different formalities shall be governed, with respect to these, by the provisions of said special laws”. To this end, the administrative reports corresponding to breaches of vehicle immobilisation performed in the administrative field of road safety must be considered as breaches of Article 76(j) of the LSV and will be referred to the corresponding Provincial Traffic Unit for the imposition of sanctions in matters of road safety.

In addition, since 2003, there has been a specific type of administrative offence for breaches of vehicle immobilisations related to the land transport regulations. Thus, Law 29/2003, which addresses the improvement of competition and safety conditions in the road transport market, partially amending Law 16/1987 on the Organisation of Land Transport (LOTT), defines for the first time, in Article 140.7, the specific offence of breaches, including “the breach of orders to immobilise or confiscate vehicles or premises” as a very serious offence. To date, this offence still exists in Article 140.12 of the LOTT and in Article 197.13 of the Regulation of the Law on the Organisation of Land Transport (ROTT), worded as a “breach of the order to immobilise a vehicle", which is considered very serious and is punishable by a fine of 4001 to 6000 euros.

As explained above, the breach of immobilisations is addressed from two different perspectives: road safety and transport. This depends on whether the road safety or road transport legislation applies to the case in hand. The main difference lies in the classification of the offence, which is defined as very serious in transport legislation and only serious in road safety legislation. In the understanding of the author of this article, its consideration as a serious offence in the field of road safety does not seem very appropriate, as to immobilise a vehicle, offences must be committed that pose a serious danger to road safety, considered in most cases as very serious offences, and breaching the immobilisation means that the same offences can continue to be committed that would seriously compromise road safety, and yet they are punished as serious offences, punished in most cases with smaller fines than the initial offence that led to the immobilisation, meaning it is more beneficial for the offender to breach the immobilisation than comply with the immobilisation.

Finally, the question arises as to whether the decriminalisation of the misdemeanour of minor disobedience completely rules out criminal proceedings to punish the perpetrators of breaching immobilisations, or whether, on the contrary, in some cases they could be punished for committing the crime of serious disobedience to police officers, as defined in Article 556.1, of the current Criminal Code, punishable by a prison sentence of three months to one year or a fine of six to eighteen months. We will look to answer this question as we proceed in this article.

2.2. Statistical analysis of offences committed on interurban roads in Cantabria (from 2018 to 2022).

To perform a statistical analysis of the breaches of vehicle immobilisations carried out by the ATGC on interurban roads in Cantabria, data for the past 5 years (2018-2022) was requested from the Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil in Cantabria.

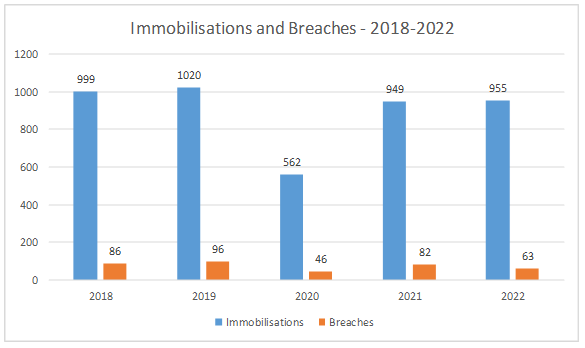

The graph below shows the data contained in the immobilisation records[1] held by the Traffic Operations Centre (COTA) of the Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil in Cantabria, containing all vehicle immobilisations related to the road safety and land transport legislation and their corresponding breaches.

|

Graph 1: Total number of immobilisations/breaches on interurban roads in Cantabria (2018-2022)

Source: Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil in Cantabria

This graph shows the total number of vehicle immobilisations performed on interurban roads in Cantabria, compared to the total number of breaches of these immobilisations, over the past 5 years (from 2018 to 2022), broken down by year, as follows:

· In 2018, there were a total of 999 immobilisations, 86 of which were breached, representing 8.6% of the total.

· In 2019, a total of 1020 vehicles were immobilised, 96 of which were breached, representing 9.4% of the total. During 2020, mobility restrictions were imposed to control the spread of the pandemic, reducing the number of immobilisations to a total of 562, of which 46 were breached, representing a percentage of 8.1%.

· During 2021, the post-pandemic period, the numbers of immobilisations increased to pre-pandemic levels, totalling 949, with 82 breaches, or 9.6% of the total.

· Finally, during year 2022, a total of 955 vehicles were immobilised, resulting in 63 breaches, representing 6.5% of the total.

During the five years covered by this study, the annual percentage of drug offences ranged between 8 and 9%, except for 2022, when it fell to 6.5%, perhaps because fewer drug tests were carried out due to a reduction in the supply of drug testing kits.

Although the rate of breaches is not alarming, they remain too high and should be reduced because of the danger they pose to road safety.

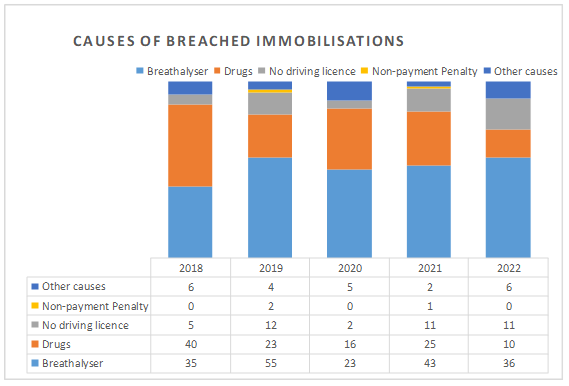

|

Graph 2: Total No. of main causes of breached immobilisations (2018-2022)

Source: Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil in Cantabria

This reflects the main causes of immobilisations breached during the years subject to study, 2018 to 2022, with the majority resulting from alcohol and drug offences and lack of a driving licence, with the number of non-payment of fines being almost negligible. As regards breaches of immobilisations resulting from infringements of transport regulations, these are included under “other causes”, together with other infringements including missing MOTs and serious defects in the vehicle. The number of such infringements is low.

The results obtained show that the most frequent breaches can be traced to the immobilisation of vehicles whose drivers were detained for alcohol and drug offences, which in turn are the main reasons why traffic officers immobilise vehicles. These breaches are particularly dangerous for road safety because of the possibility that the perpetrator may continue to drive while over the limit or having consumed drugs, this being a particularly relevant factor in the production of road accidents.

In 2021, 49.4% of drivers killed in road crashes were driving under the influence of alcohol, drugs or psychotropic drugs, and 75% of drivers who returned a positive breathalyser test had a very high blood alcohol level, of 1.2 grams/litre or more. (Pilar Llop, Ministra de Justicia, 2022)This data shows the seriousness of the problem.

3. IMMOBILISATION BY THE TRAFFIC UNIT.

In terms of internal regulations, the ATGC has its “Unit Rules”, which consist of a compendium of rules and procedures that regulate any aspect related to the service of the Civil Guards working at the Traffic Unit, in the different categories of motorists and accident investigations, and their missions of surveillance, regulation, assistance and control of traffic and transport, investigation as court-appointed traffic police, protection at sporting events, as well as in relation to dealing with citizens.

Immobilisation is regulated in these regulations, set out in a dispersed manner in Title 6 relating to the “Procedure for controlling alcohol and drug consumption in relation to road safety” (specifying the specific way of immobilising vehicles in cases of alcohol and drug consumption, and the way of proceeding in case of breaches) and in Title 6 relating to the “Procedure for the control and monitoring of traffic, the circulation of motor vehicles and road transport” (establishing a brief procedure for immobilising vehicles covered by the cases included in the previously repealed Road Safety Law, a series of measures to be adopted in such cases, the way of lifting an immobilisation and breach thereof, and describing vehicle immobilisations in relation to transport by road, establishing action guidelines to perform immobilisations). However, it does not include the different cases applicable to the immobilisation of vehicles related to road safety and land transportation, nor does it resolve a number of the operational problems that arise when immobilisations are carried out, including but not limited to those caused when lifting immobilisations performed by a different patrol and the use of immobilisers that have different keys or the way to proceed in the event of breaches in which the immobiliser is damaged or disappears.

It is therefore considered necessary to create an operating procedure for immobilising vehicles in a standardised way, covering all possible cases, whether under the road safety or road transport regulations, and that is updated and establishes common guidelines for action to ensure the effectiveness of the immobilisation and help to prevent breaches from occurring.

3.1. Means used to immobilise vehicles.

To secure immobilisations and to prevent breaches, the use of immobilisers which prevent the vehicle from being driven is essential. At present, the following types of immobilisers are available to the ATGC:

- “Spigot” type motorbike immobiliser, to be fitted to one of the wheels. Given their size and flexibility, they can be placed on four-wheeled vehicles and motorbikes.

Image no. 1: Immobiliser for motorbikes.

Source: Prepared internally.

- “Clamp” type vehicle immobiliser, fitted to the steering wheel and one of the pedals. Given their size and flexibility, they can be placed on four-wheeled vehicles and motorbikes.

Image no. 2: Steering wheel-pedal clamp immobiliser.

Source: Prepared internally.

- “Clamp” type immobiliser for vehicles, fitted to large wheels. This type of immobiliser was provided by the Directorate General for Transport and Communications in Cantabria for use by officers of the Traffic Unit in Cantabria with specific road transport monitoring duties. Given its size, it can only be placed on four-wheeled vehicles and is suitable for immobilising large vehicles, such as lorries and buses.

Image no. 3: Large wheel clamp immobiliser.

Source: Prepared internally.

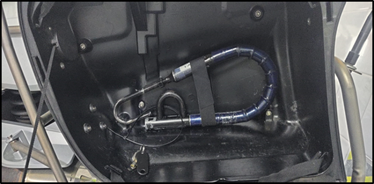

The first two immobilisers offer the major advantage of being transportable on a motorbike, which facilitates the practice of immobilisations when the service is performed on this vehicle, since to secure such a device, there is no need for another four-wheeled patrol car carrying an immobiliser. When performing such services using a motorbike, there is less and less space in the side cases to carry all the necessary equipment, including the immobiliser. It would therefore be advisable to find the right place in the side case for the “steering wheel-pedal” type immobiliser, which is the most commonly used as it can be fitted to most vehicles, it takes up less space and is also well secured, preventing it from falling out and getting lost each time the case is opened.

|

Image no. 4: Proposal for securing the immobiliser inside the side case of a motorbike.

Source: Prepared internally.

From an operating perspective, the main drawback of these immobilisers is that each one uses a different key. This may seem like an unimportant detail, but when it comes to optimising human resources for the provision of the service, this becomes a major problem. This is on account of the fact that, to lift the immobilisation of a vehicle, only the patrol with the key for the immobiliser used can do so, although another may be available closer by. In the event of not being able to lift the immobilisation during their shift, they have to hand the key to the patrol that takes over from them, complicating the situation further if it is not from the same unit and a large number of immobilisations have been performed. This is in addition to the risk of the keys being lost, meaning that sometimes they have to be passed through several patrols until the vehicle's immobilisation is lifted. A universal key for all immobilisers would, in most cases, improve the response time for lifting immobilisations, as it could be performed by the nearest available patrol to the location of the immobilised vehicle, and solve the problem of locating the patrol that has the key for each immobiliser used to lift immobilisations.

The effectiveness of immobilisation depends to a large extent on the fitting of an immobiliser to prevent the vehicle from being driven. These immobilisers available to the ATGC have to be placed correctly and effectively in order for the device to be secured. Although they may seem easy to install, without the need for training, it is likely that the first time they are used, they will not be fitted correctly, especially in relation to the second and third devices mentioned above, making it easier to break them.

Based on the professional experience of the signatory, the installation features for each type of immobiliser are outlined below:

· The “spigot” type immobiliser: this is the easiest to install on motorbikes, as it can simply be placed on one of the motorbike's wheels and, if it has a fixed point, attach it here as well, to secure it more effectively.

Image no. 5 and 6: Fitting of the “spigot” type immobiliser to the front wheel of a motorbike.

Source: Prepared internally.

· The "steering wheel-pedal clamp" type immobiliser: this is the most commonly used immobiliser as it can be fitted to most vehicles. The problem of installation arises when the clamp is not long enough to engage both the pedal and the steering wheel, or because the width of the vehicle's steering wheel means it cannot be fitted, or if it can, it is too tight and can damage the material with which the steering wheel is lined.

Image no. 7: Fitting the“steering wheel-pedal clamp” type immobiliser to a vehicle.

Source: Prepared internally.

· The “large wheel clamp” type immobiliser: is used to immobilise large vehicles such as lorries and buses. Due to its size and weight, having two people fit this trap is recommended.

Image no. 8: Fitting the wheel clamp immobiliser on a lorry.

Source: Prepared internally.

It is for these reasons that it is considered that the means available to the ATGC to ensure immobilisations are adequate, although it would be advisable to have another type of immobiliser to make up for cases in which it is not possible to install the “steering wheel-pedal clamp” type immobiliser or it is not possible to access the inside of the vehicle for its installation, and in turn, to establish rules explaining how the different types of immobilisers allocated to the Units are installed, so that any Civil Guard officer who has to use them to immobilise a vehicle can do so with no doubts about the correct and effective way of installing them.

4.- INTERVIEWS AND SURVEY.

With a view to providing further details of the possible problems and specific features related to the matter in question, several interviews have been carried out with different authorities and heads of police forces related to road safety, as well as with members of the Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil in Cantabria, whose contributions will help to further clarify the different situations initially raised.

Extracts from interviews conducted with different road safety authorities:

On 17 March 2023, the Provincial Head of Traffic in Cantabria, Mr. José Miguel Tolosa Polo, was interviewed, as a result of which, the following conclusions could be reached:

· The cases set out in Article 104 of the LSV require, given their immediacy, seriousness and search for a reduction in the risks associated with road safety, a guarantee that ensures the effectiveness of each action, thus avoiding the damage that the alleged breaches could cause.

· Technical advances in the mechanisms for performing immobilisations should allow us to have more robust and efficient tools to ensure the effectiveness of the measures. It is also important to have a sufficient number of devices that can be used at different events (popular festivals, music festivals, different agglomerations, etc.) where the number of immobilisations to be performed could presumably be high.

· Given the risk to road safety that breaching the immobilisation generates, a different classification of this type of conduct in the legislation on Traffic and Road Safety is appropriate, and a higher financial penalty seems logical to dissuade possible offenders from engaging in such conduct. As regards the penalty of removing points from a driver's licence, we could consider that as this conduct is not always attributable to the driver and which clearly disregards the orders of the Authority and its agents, only a financial penalty is applicable (with an increase in the corresponding financial sum), but without deducting points.

On 20 March 2023, the Road Safety Prosecutor in Cantabria, Mr. Jesús Dacio Arteaga, was interviewed and the main takeaways from the interview have been summarised below:

· The offence of serious disobedience in Article 556.1 of the CP is very difficult to apply in cases in which the immobilisation of vehicles is breached, on account of the requirements currently demanded by case law, both in terms of its application and its criminalisation. Although the possibility of applying the offence of disobedience to law enforcement officers for breaches of the immobilisation of vehicles has not been ruled out, in reality or in terms of its practical application, it should be based on the specific case and circumstances, with its use being very restricted.

· In cases where the immobiliser is damaged or the immobiliser is removed from its place, it is considered that the offences of theft or damage can be resorted to in criminal law. Probably a misdemeanour, either under Article 234.2 or Article 263.2, although the value of the immobilisers is unknown, he believed that they would not be more than €400.

The applicability of the offence of theft or damage will always depend on the intention of the perpetrator. In these cases, we generally assume that the intention is to breach the immobilisation, as direct intent in the first degree. Secondly, their intent is to cause damage, which is what the perpetrator inevitably does (direct intent in the second degree) and the theft of the device seems very secondary; he does not consider malice or profit in the motive, although residually, the offence of theft could be applied under the doctrine of eventual malice.

Interviews with the heads of police forces responsible for road safety.

On 20 February 2023, the Chief Commissioner of the Road Safety Division at the Navarre Regional Police, Mr. José Antonio Gurrea Martínez, was interviewed and the most important aspects of this interview are outlined below:

· For vehicle immobilisations, "steering wheel-dashboard" type immobilisers are available, and for vehicles that cannot be accessed from inside , "wheel clamp" type immobilisers are available, all with a universal key for each type of clamp.

· In relation to the statistics regarding the breach of immobilisations, in 2022, a total of 2,026 vehicles were immobilised in the province of Navarre, 12 of which were breached, representing 0.59% of the total.

· In the event of a breach of an immobilisation that involves moving the vehicle with the clamp still attached to it, which will almost certainly be destroyed or damaged in the process, the perpetrator will be investigated for an alleged offence of damage, in addition to the corresponding administrative complaint being filed for the breach of the immobilisation.

· The Regional Police of Navarre has a standardised working procedure for the immobilisation of vehicles, which indicates the procedure to follow in this case.setting out the procedure to be followed in this case, the unit to be informed of the immobilisation and its subsequent lifting, where to carry it out, which form to fill in, etc.

On 28 February, the Deputy Chief Inspector of the Local Police of Torrelavega (Cantabria), Mr. Enrique Sáez Trigueros, was interviewed. Worth particular note was the following:

· Vehicles are immobilised on the spot if the vehicle is parked properly, and if not, they are towed to the municipal vehicle depot.

· As regards the statistics on breaches of immobilisations, in 2022, a total of 405 vehicles were immobilised, with 7 of these immobilisations being breached, which represents 1.72% of the total. This means that the usual procedure of transferring vehicles to the municipal depot is the most effective.

· An operational protocol is in place to carry out immobilisations and subsequently lift them.

On 22 February 2023, the Chief Major of the Traffic and Road Safety Division of the Guarda Nacional Republicana de Portugal was interviewed. The most significant points of this interview are summarised below:

· For vehicle immobilisations only wheel clamp immobilisers are available for passenger vehicles and vans.

· Although there are no statistics available on the number of breaches of immobilisations produced; on urban roads "wheel-lock" immobilisers are very effective (as these devices are difficult to remove). In all other cases, the immobilisations are notified in writing, and drivers usually respect the immobilisation for fear of committing an alleged offence of disobedience if they breach the immobilisation.

· There is an internal rule in place that regulates how vehicle immobilisations are to be performed.

Survey carried out with members of the Traffic Sector of the Civil Guard in Cantabria.

On 3 March 2023, an anonymous survey was carried out online amongst members of the Traffic Unit of the Civil Guard in Cantabria, belonging to the Traffic Details of Torrelavega, Laredo, San Vicente and Reinosa. In total, 35 responses were received.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the survey:

· All respondents consider that effective vehicle immobilisation is very important for road safety.

· The first time they immobilised a vehicle, almost half of them (45.7%) did not know how to install the immobiliser correctly and effectively.

· 71.4% responded that they lacked adequate training to effectively fit the different types of immobilisers available to the ATGC.

· Concerning the problems encountered by those surveyed when lifting the immobilisation of a vehicle using an immobiliser at their Unit, 20% of them claim to have difficulties because there is no single protocol for liaising among the members of the Unit that a vehicle has been immobilised, due to the problems attributable to having different keys for each immobiliser, which means that on numerous occasions they do not know who has the key and it takes time for it to be found. This represents a handicap for the use of this measure, and because they do not have practical training with the immobiliser for large vehicles. In addition, when the immobiliser used is from another unit, the percentage of respondents who experienced problems removing the immobiliser increased to 48.6%, mainly citing difficulties in locating the key belonging to another unit, especially when the other unit's patrol has finished its service.

· Almost all respondents consider it necessary to develop a specific procedure regulating the practice of immobilisations and subsequently lifting them.

· The majority believe that there would be fewer offenders if the administrative penalty for breaking an immobilisation were increased.

· In response to the free text question asking for suggestions about how to improve the practice of vehicle immobilisations to prevent breaches, almost all responses suggested providing adequate training in the installation of immobilisers, having a universal key for opening all immobilisers, at least at a Sector level, increasing the number of immobilisers available, using other immobilisers that avoid having to access the passenger compartment of the vehicle (including wheel clamps), using other more effective mechanisms such as the confiscation of the immobilised vehicle by crane to a depot until the reasons for the breach no longer exist and increasing the penalty for breaches that do occur.

CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS

The breach of vehicle immobilisations allows the continuation of certain specified offences that gave rise to the application of the provisional measure for immobilising a vehicle, with the serious problem that this may entail in case of the persistence of the risk to the legal right that the different applicable legislations relating to road safety and land transport management, or even criminal law, were intended to protect.

This research aims to analyse the breaches of vehicle immobilisations on interurban roads in Cantabria over the past 5 years (from 2018 to 2022), with a view to defining the problem and being able to answer the initial question: Can breaches of vehicle immobilisations on interurban roads in Cantabria be avoided or minimised by improving the practice of immobilisations undertaken by the ATGC and by increasing the sanctions and penalties applied to the perpetrators? It emerged that once improvement could be based around the optimisation of vehicle immobilisation practices at an operational and police level, as well as an adaptation of the sanctions and penalties associated with breaches to deter potential offenders.

Looking deeper into the problems caused by the application of immobilisations on interurban roads in Cantabria, a statistical analysis of the immobilisations of vehicles carried out by the Traffic Unit of the Civil Guard on these roads and their subsequent breaches was carried out, focussing the study on the past 5 years (from 2018 to 2022). In view of the results obtained, it could be concluded that there was a considerable number of breaches, the annual percentage standing at between 8 and 9 % of the immobilisations carried out, except in 2022, when this percentage dropped to 6.5 %, possibly due to the fact that fewer drug tests were carried out than previously. As regards the causes of immobilisations, it was found that the number of breaches related to land transport regulations was insignificant in comparison to those related to road safety, with the majority being breached related to alcohol and drug consumption, which in turn are among the most dangerous offences for road safety due to their significant weight in the production of fatal road accidents.

At this point, it is worth looking at the other questions posed at the start of this study:

· Are there any procedures in the internal regulations of the ATGC for performing vehicle immobilisations?

Although the ATGC has several procedures in place in its internal regulations to deal with vehicle immobilisations, there is a clear need to create a single operational procedure for the immobilisation of vehicles which is up to date and covers the cases established in relation to road safety and land transport, with the respective exceptions, and which establishes common operational guidelines for carrying out immobilisations and subsequently lifting them, as well as in cases of breaches. This necessity is reaffirmed by the survey performed among the members of the Traffic Unit of the Guardia Civil in Cantabria, as part of which 80% of those surveyed considered it necessary to establish, at an operational level, a specific procedure for regulating the practice of immobilisations and subsequently lifting them. In addition, all the heads of the police forces responsible for road safety who were interviewed responded that they had an operational procedure, protocol or internal rule in place for the immobilisation of vehicles as part of law enforcement.

· Can the effectiveness of the means or mechanisms used by ATGC to immobilise vehicles be improved?

The immobilisers available to the ATGC are of three types, a “spigot” type clamp for immobilising motorbikes, a “steering wheel-pedal clamp” type which can be used on most vehicles, and a “large wheel clamp” type for immobilising large vehicles such as lorries and buses. Although these immobilisers provide a number of advantages and disadvantages from an operational perspective, they are considered in themselves to be of an acceptable effectiveness in securing vehicle immobilisations. The problem is that most vehicles can only be immobilised using the “steering wheel-pedal clamp” type immobiliser and there is no other type of immobiliser available which covers other forms of installation and can compensate its shortcomings. It is also necessary to establish rules that explain the correct and effective way of placing the different types of immobilisers to the officers, since based on the results of the survey performed amongst the Civil Guards belonging to the Traffic Unit in Cantabria, almost half of them did not know how to install the immobiliser correctly and effectively the first time they immobilised a vehicle, and 71.4% stated that they did not have adequate training to install the different types of immobilisers used by the ATGC.

· Should the sanctions and penalties to be imposed on those responsible for breaches be increased?

Breaches of vehicle immobilisations are considered offences of disobedience to law enforcement officers and their punishment will depend on the legislation applied. In criminal law, breaches can only be punished as a form of serious disobedience of agents of the authority, as reflected in Article 556.1 of the Criminal Code and punishable by a prison sentence of 3 months to 1 year or a fine of 6 to 8 months. Based on the interview with the Road Safety Prosecutor in Cantabria, its application should be very limited, applied to specific cases and particularly serious circumstances, since in accordance with the general criminal principle of minimum intervention, administrative sanctions should be applied first, leaving criminal action as a last resort.

Under land transport legislation, breaching an immobilisation order is classified as a specific offence (Article 140.12 of the LOTT and Article 197.13 of the ROTT), considered as a very serious offence and punishable by a fine of between 4,001 to 6,000 euros. The infraction and sanction are considered appropriate, both in its classification as very serious and the value of the fine, as it is assumed that to serve a preventive purpose, it must be classified as at least the most serious infringement that it is intended to prevent from being committed with the application of the immobilisation measure, in such a way that a breach of the immobilisation cannot be more advantageous.

On the other hand, in road safety matters, the offence of breaching a vehicle immobilisation is not a specific offence, rather it is included in the range of conducts considered as an offence for not respecting the instructions or orders of law enforcement officers, classified as a serious offence (Article 76.j, of the LSV) and punishable by a fine of 200 euros and the deduction of 4 points from the perpetrator’s driving licence. This classification as a serious offence does not seem to be proportionate to the serious damage caused to road safety on account of the fact that a very serious offence, such as those related to alcohol and drug consumption, can still be committed, nor does the sanction have a deterrent effect on the potential offender, because the payment of a fine of €100 (applying the discount) is probably more preferable than the damage caused by not being able to use the vehicle. Likewise, this stance is in line with the comments made by the Provincial Chief of Traffic in Cantabria in his interview, who indicated that given the significance of breaching the immobilisation order in relation to road safety, a different classification of this conduct in the LSV would seem appropriate, as well as a higher financial penalty to dissuade hypothetical offenders, without resulting in the deduction of points, since this conduct will not always be the responsibility of the driver and represents clear disobedience of the authority and its agents.

On the basis of these conclusions, below we verify whether the hypotheses set out at the start of this text are valid:

· “If there were an operational procedure in the ATGC for carrying out immobilisations, would the number of breaches be reduced?”

In the response to this question, it has been found that there is a need to create an operating procedure for action in relation to vehicle immobilisations that clarifies how ATGC agents should proceed and resolve their difficulties to ensure the highest level of effectiveness of the measure and prevent breaches from occurring. The hypothesis was therefore validated.

· “If the ATGC were to use more effective means or mechanisms to carry out immobilisations, would it be possible to prevent breaches?”

The answer to this question shows that the means available to the ATGC to perform vehicle immobilisations are effective, although on account of the fact that there is only one type of immobiliser used to carry out the majority of immobilisations, it would be necessary to provide a different immobiliser model to make up for installation shortcomings, meaning that no immobilisation is left unsecured through the use of immobilisers and these means should also be accompanied by rules explaining their installation to further guarantee their effectiveness. Therefore, this hypothesis can only be partially validated.

· “If sanctions and penalties for breaching immobilisations were tougher, could the risk of them materialising be reduced?”

In response to this, it can be concluded that it would be necessary to establish a specific offence for breaches of vehicle immobilisations carried out to ensure road safety, classifying them in the LSV as a very serious offence with a higher financial sanction with a view to having a greater preventive effect. However, in criminal and transport matters, penalties and sanctions are considered sufficient and would not need to be strengthened. Consequently, this hypothesis can only be partially validated.

Finally, and with a view to answering the initial question, it can be concluded that if the practice of immobilisations carried out by the ATGC were improved by implementing an operational procedure for immobilising vehicles and the provision of sufficient and efficient immobilisers, with their rules of use, to guarantee the effectiveness of the measure, and a reform of the LSV were undertaken to establish the specific offence of breaching the immobilisation order, classified as a very serious offence and punishable with a higher fine, it would be possible to avoid or minimise the breach of vehicle immobilisations.

Based on the results of the study, the following proposals for improvement have been put forward:

1. Propose that the DGT establish a specific offence for “breaking the order to immobilise a vehicle issued by traffic enforcement officers”, classified as a very serious offence and punishable by a fine of 1,000 euros, without deduction of any points.

2. Include an operational procedure in the Traffic Manual for action in relation to vehicle immobilisations and a technical standard on the correct and effective installation of vehicle immobilisers, pursuant to the provisions of Article 4 of General Order No. 30/2021 of 9 September, which regulates Traffic and the structure, organisation and functions of the ATGC (Dirección General de la Guardia Civil, 2021).

3. In the technical specifications for new motorbike procurement contracts, include the installation of a fastening for “steering wheel-pedal clamps”, which is the most commonly used, inside the side cases, in such a way that it is placed in the lower recess at the bottom of the case, thus optimising space inside the cases and ensuring that the immobiliser is properly secured and does not fall out every time the case is opened.

4. Provide a larger number of immobilisers so that all four-wheeled vehicles and motorbikes are equipped with at least one immobiliser, and a minimum of two other incident immobilisers are stored at the Unit to enhance the vehicle module used when it is expected that a high number of immobilisations may occur.

5. Acquire immobilisers with a universal key to improve the operability of the patrols that carry out the immobilisations and subsequently lift them.

6. Supply another type of immobiliser to make up for the installation shortcomings of the “steering wheel-pedal clamp” type immobiliser, as this is the only immobiliser available to immobilise most vehicles, with the exception of motorbikes and large vehicles, such as wheel clamp type immobilisers for passenger cars and vans (this would avoid having to enter the passenger compartment of the vehicle to be immobilised) or dashboard steering wheel clamp type immobilisers (does not require any adjustment to the clamp length). As a proposal for future research, work could be performed to develop computer software that can be downloaded to the control unit of the vehicle to be immobilised via USB connection, preventing the vehicle from being started and subsequently allowing the immobilisation to be lifted.

7. Establish operational training on vehicle immobilisations and a practical explanation on the correct and effective installation of the different types of immobilisers in the training action performed by the Units.

8. Coordinate other more effective mechanisms with the DGT to supplement the means used by the ATGC to guarantee the maximum effectiveness of immobilisations in cases in which a possible breach seriously compromises road safety, especially involving drivers who are repeat offenders, such as having a towing service to transfer the immobilised vehicle to its base or to authorised municipal depots until the causes of the immobilisation no longer exist, with the offender paying the costs.

9. Register offenders who breach vehicle immobilisations in the Guardia Civil's “SIGO- Sistema Integrado de Gestión Operativa” database, in such a way that this information can be consulted by the patrols on duty and they can adopt the appropriate preventive measures for monitoring and securing the immobilisation, helping to avoid another possible breach.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Agrupación de Tráfico de la Guardia Civil. (Normativa interna). Normas de la Agrupación. Título 2 Nombramiento del servicico, Título 11 Proc. de control de la alcoholemia y el consumo de otras drogas en la seguridad vial, Título 6 Proc. de control y vigilancia del tráfico, la circulación de vehículos a motor y el transporte por carretera.

Baños, A. (03 de febrero de 2022). tuteorica.com. Obtenido de https://tuteorica.com/blog/blog-legislacion/inmovilizacion-del-vehiculo-por-carecer-de-seguro/

DGT. (6 de agosto de 2010). Escrito de respuesta a consulta de la Agrupación de Tráfico de la Guardia Civil sobre inmovilizaciones vehículos en carretera. Fuente: Escuela de Tráfico de la Guardia Civil.

DGT Instrucción 14/V-106, 14/S-133, 14/C-114. (8 de mayo de 2014). Policialocalaragon.com. Obtenido de http://www.policialocalaragon.com/legislacion/trafico/instrucciones/dgt_instruccion_14-v-106_14-s-133_14-c-114_ley_6-2014_08-05-2014-.pdf

Dirección General de la Guardia Civil. (14 de septiembre de 2021). Orden General número 30/2021 de 9 de septiembre, por la que se regula la especialidad de Tráfico y la estructura, organización y funciones de la Agrupación de Tráfico de la Guardia Civil. España: BOC núm. 38. .

Dirección General de Transporte Terrestre. (4 de septiembre de 2009). Escrito de respuesta a consulta de la Agrupación de Tráfico de la Guardia Civil sobre inmovilizaciones vehículos extranjeros. Fuente: Escuela de Tráfico de la Guardia Civil.

Fiscal de Sala Coordinador de Seguridad Vial. (02 de marzo de 2020). Ministerio Fiscal. Obtenido de Fiscal.es: https://www.fiscal.es/search?p_p_id=com_liferay_portal_search_web_search_results_portlet_SearchResultsPortlet&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&_com_liferay_portal_search_web_search_results_portlet_SearchResultsPortlet_mvcPath=%2Fview_cont

Jefatura del Estado. (31 de julio de 1987). Ley 16/1987, de 30 de julio, de ordenación de los transportes terrestres. España: BOE número 182.

Jefatura del Estado. (24 de noviembre de 1995). Ley Orgánica 10/1995, del Código Penal. España: BOE núm. 281. Obtenido de https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/1995/11/23/10/con

Jefatura del Estado. (9 de octubre de 2003). Ley 29/2003, de 8 de octubre, sobre mejora de las condiciones de competencia y seguridad en el mercado de transporte por carretera, por la que se modifica, parcialmente, la Ley 16/1987, de 30 de julio, de Ordenación de los Transportes Terrestres. España: BOE núm. 242.

Jefatura del Estado. (5 de julio de 2013). Ley 9/2013, de 4 de julio, por la que se modifica la Ley 16/1987, de 30 de julio, de Ordenación de los Transportes Terrestres y la Ley 21/2003, de 7 de julio, de Seguridad Aérea. España: BOE núm. 160.

Jefatura del Estado. (2 de octubre de 2015). Ley 39/2015, de 1 de octubre, del Procedimiento Administrativo Común de las Administraciones Públicas. España: BOE núm. 236.

Jefatura del Estado. (31 de marzo de 2015). Ley Orgánica 1/2015, de 30 de marzo, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 10/1995, de 23 de noviembre, del Código Penal. España: BOE núm. 77.

Jefatura del Estado. (31 de marzo de 2015). Ley Orgánica 4/2015, de 30 de marzo, de protección de la seguridad ciudadana. España: BOE núm. 77.

Mínguez, J. (11 de abril de 2018). Lawyerpress.com. Obtenido de https://www.lawyerpress.com/2018/04/11/el-decomiso-del-vehiculo-en-los-delitos-contra-la-seguridad-vial/

Ministerio de la Presidencia. (21 de noviembre de 2003). Real Decreto 1428/2003, Reglamento General de Circulación. España: BOE núm. 306 .

Ministerio de la Presidencia. (05 de Noviembre de 2004). Real Decreto Legislativo 8/2004, de 29 de octubre, por el que se aprueba el texto refundido de la Ley sobre responsabilidad civil y seguro en la circulación de vehículos a motor. España: BOE núm. 267.

Ministerio de Transportes, Turismo y Comunicaciones. (8 de octubre de 1990). Real Decreto 1211/1990, de 28 de septiembre, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento de la Ley de Ordenación de los Transportes Terrestres. España: BOE número 241.

Ministerio del Interior. (31 de Octubre de 2015). Real Decreto Legislativo 6/2015, de 30 de octubre, por el que se aprueba el texto refundido de la Ley sobre Tráfico, Circulación de Vehículos a Motor y Seguridad Vial. España: BOE número 261, páginas 103167 a 103231.

Pilar Llop, Ministra de Justicia. (20 de julio de 2022). Lamoncloa.gob.es. Obtenido de https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/serviciosdeprensa/notasprensa/justicia/Paginas/2022/200722-informe-toxicologico-victimas-trafico.aspx

STC núm. 108/1984, de 26 de noviembre. (21 de diciembre de 1984). Tribunal Constitucional. España: BOE supl. al núm. 305, página 8, II Fundamentos Jurídicos, apartado b).

STS 672/2019. (15 de enero de 2019). CENDOJ. Obtenido de Poderjudicial.es: https://www.poderjudicial.es/search/indexAN.jsp