Luis del Río Montesdeoca

Safety road Prosecutor Coordinator

NEED FOR A SPECIALISED ROAD SAFETY PROSECUTOR'S OFFICE

NEED FOR A SPECIALISED ROAD SAFETY PROSECUTOR'S OFFICE

Summary: 1. SPECIALISATION WITHIN THE PROSECUTION SERVICE 2. ROAD SAFETY COORDINATION PROSECUTOR. STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S ROAD SAFETY UNIT 3. FUNCTIONS OF THE ROAD SAFETY COORDINATING PROSECUTOR 4. SPECIALISED SECTIONS IN EACH REGIONAL PROSECUTOR'S OFFICE. DEPUTY PROSECUTORS 5. STATISTICS. 2023 STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL REPORT AND 2022 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT ROAD ACCIDENT BALANCE SHEET 6. 2030 ROAD SAFETY STRATEGY 7. GENERAL MATTERS IN RELATION TO THE PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ROAD SAFETY 8. THE IMPORTANCE OF ROAD SAFETY 9. VICTIMS 10. CONCLUSIONS

Resumen: El tema de este trabajo es responder a la siguiente pregunta: ¿es necesario una Fiscalía especializada en seguridad vial?

Para ello abordamos la especialización del Ministerio Fiscal, introducida en nuestro ordenamiento jurídico por la Ley 24/2007.

La seguridad vial es un aspecto importante en la vida cotidiana de todos los ciudadanos. Todos los esfuerzos son pocos para luchar contra esta lacra que supone un coste humano y social intolerable, máxime en una sociedad como la nuestra con el desarrollo científico y tecnológico del que dispone. Incluso en términos económicos el coste es elevado.

Así mismo, analizamos diferentes datos estadísticos y cuestiones sobre el presente y el futuro de la seguridad vial.

Sin olvidar una referencia a las víctimas que juegan un papel esencial y deben tener la oportunidad de ser escuchadas.

Finalmente, incluimos unas breves conclusiones de todo lo expuesto anteriormente para intentar contestar a lo planteado en el trabajo.

Abstract: This paper aims to answer the following question: is there a need for a specialized Public Prosecutor's Office for road safety?

For this purpose, I analyze the specialization of the Public Prosecutor's Office introduced into our legal system by Act 24/2007.

Road safety is an important aspect of everyday life for all citizens. All efforts are not enough to combat this scourge, which involves an intolerable human and social cost, especially in a society such as ours with the scientific and technological development at its disposal. Even in economic terms, the cost is high.

Likewise, we analyze different statistical data and questions about the present and future of road safety.

We cannot forget a reference to the victims, who play an essential role and must have the opportunity to be heard.

Finally, we include some brief conclusions on the above-mentioned points to answer the questions raised in the paper.

Palabras clave : delitos contra la seguridad vial, vehículo a motor, conductor, riesgo, víctima.

Keywords: road safety offences, motor vehicle, driver, risk, victim.

1. SPECIALISATION WITHIN THE PROSECUTION SERVICE

As we know, the constitutional model of the Public Prosecutor's Office[1] establishes the basic principles of legality and impartiality. These principles are absolutely unquestionable in a democratic society. It also sets out the principles of unity of action and hierarchical reporting[2], which are subordinate to the aforementioned principles.

The principle of unity of action of the Public Prosecutor's Office[3] has, in turn, been linked to the principle of equality before the law (Articles 1.1 and 14 of the Spanish Constitution) and to the principle of legal certainty[4] (Article 9.3 of the Spanish Constitution), which are essential in the rule of law. In turn, hierarchical reporting must be understood as an instrumental principle at the service of unity of action.

It is on the basis of these basic principles that sets the groundwork for a fully democratic Public Prosecutor's Office at the service of society, thereby overcoming any authoritarian vestiges of yesteryear.

Returning to the principle of unity of action, this principle seeks a unitary interpretation and application of legal rules in the different courts (which is in the general interest of the highest level) thereby achieving the minimum and necessary certainty of the legal system[5].

When applied, rules may give rise to different and even contradictory interpretations between different court authorities in the same or different regions. This is often particularly relevant in cases dealing with new realities (e.g. road safety, personal mobility vehicles[6], for example) or recent legal reforms.

We cannot overlook the important reforms that have taken place in relation to this matter:

Organic Law 15/2003, of 25 November, amending Arts. 152, 379, 381, 382 of the Criminal Code.

Organic Law 15/2007, of 30 November, affecting Arts. 379, 380, 381, 382, 383, 384, 385 and the heading of Chapter IV, Title XVII, Book II.

Organic Law 5/2010, of 22 June, amending Arts. 379, 381, 384 and introducing Arts. 385a and b

Organic Law 1/2015, of 30 March, affecting Articles 142 and 152 of the Criminal Code.

Organic Law 2/2019, of 1 March, amending Articles 142, 152 and 382 and introducing Arts. 142 bis, 152 bis and 382 bis of the Criminal Code.

Organic Law 11/2022, of 13 September, amending Arts. 142, 152 and 382 bis of the Criminal Code.

As well as the innumerable Circular Notices, Instructions and Consultations issued by the State Attorney General that also refer to this matter, including but not limited to:

Firstly, among those directly affecting the matter in hand, Circular 10/2011, on criteria for the unity of specialised action of the Public Prosecutor's Office in matters of Road Safety.

In addition to Instruction 3/2006, on criteria for action by the Public Prosecutor's Office for the effective prosecution of criminal offences related to the circulation of motor vehicles.

Finally, Consultation 1/2006, on the legal-criminal qualification of driving motor vehicles at extremely high speeds.

More incidentally, the following also address road safety issues:

Circular Notice 1/2019, on common provisions and security measures for technological investigation proceedings in the Criminal Prosecution Law, and Circular Notice 2/2019, on the interception of telephone and telematic communications[7].

Circular 4/2019, on the use of technical devices for image capturing, tracking and tracing[8].

Circular 1/2015, on guidelines for the exercise of criminal action in relation to minor offences following the criminal reform operated by Organic Law 1/2015.

Circular 3/2015, on the transitional system following the reform implemented by Organic Law 1/2015.

Circular 9/2011, on criteria for the unity of specialist action by the Public Prosecutor's Office in matters of juvenile reform[9].

Circular 3/2010, on the transitional system applicable to the reform of the Criminal Code implemented by Organic Law 5/2010 of 22 June.

Instruction 8/2005, on the duty of information in the protection of victims in criminal proceedings.

Circular 1/2003 on the procedure for the rapid and immediate prosecution of certain crimes and misdemeanours and amending the abbreviated procedure.

Others correspond to organisational aspects of the speciality in the different Prosecutor's Offices:

Instruction 5/2007, on Prosecutors responsible for Coordinating Workplace Accidents, Road Safety and Alien Affairs and on the respective Sections of the Regional Prosecutor's Offices.

Instruction 5/2008, on the adaptation of the system for the appointment and status of the Delegates of the specialised sections of the Public Prosecutor's Offices and the internal system of communication and relations with the delegated areas of specialisation following the reform of the Organic By-Laws of the Public Prosecutor's Office (hereinafter EOMF) by Law 24/2007 of 9 October.

Instruction 1/2015, on issues in relation to the functions of the Coordinating Prosecutors and Deputy Prosecutors.

Instruction 11/2005 on the effective implementation of the principle of unity of action established in Art. 124 of the Spanish Constitution.

Instruction 1/2014 on the reports of the bodies at the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the State Attorney General.

Instruction 1/2018 on the publicity of the statistical data of the Reports.

Furthermore, the traditional cognitive limitation of the appeal for reversal did nothing to help to improve the situation either. However, Law 41/2015, of 5 October, together with the amendment of the second instance in criminal matters, remodelled the reversal for it to effectively fulfil its function of unifying criminal doctrine. Offences that could not previously be subject to such an appeal can now be appealed in court, thus unifying the criteria for the interpretation of different types of criminal offences. This will undoubtedly contribute to improving the implementation of constitutional values such as equality before the law and legal certainty. The agreement of the non-jurisdictional Plenary Session of Chamber II of the Supreme Court of 9 June 2016 issued an agreement on the unification of criteria on the scope of the reform of the Criminal Prosecution Law. It is worth noting that one of the criteria they approve states that "appeals must be for reversal. Those lacking such an interest must be inadmissible (Art. 889, paragraph 2), it being understood that the appeal is for reversal, pursuant to the statement of grounds:

(a) whether the ruling under appeal is openly contrary to the case-law of the e Court,

b) if it resolves questions on which there is contradictory case law of the provincial courts,

(c) if it applies rules that have not been in force for more than five years, provided that, in the latter case, there is no established Supreme Court case law relating to earlier rules of the same or similar content.

As indicated in Instruction 11/2005 on the effective implementation of the principle of unity of action established in Art. 124 of the Spanish Constitution, the mission of promoting the action of Justice in the defence of legality, citizens' rights and the public interest protected by law that Article 124 of the Constitution attributes, as well as the broad legitimisation that the legal system grants to it, place the Public Prosecutor's Office in a particularly suitable position to promote the creation of case law criteria that overcome inequalities and their application in all jurisdictional bodies. This requires unity of action which, in turn, implies unity of criteria.

The complexity of the legal system and of the problems arising from its application calls for the need for specialisation in order to articulate the principle of unity of action, in addition to the traditional mechanisms (circulars, instructions, consultations and orders of the State Attorney General). In this sense, State Attorney General Instruction 5/2008 indicates that “the promotion of the specialisation of prosecutors, as a requirement resulting from the complexity of the law and as an almost indispensable means of reinforcing the principle of unity of action, guaranteeing legal certainty (...) has been a constant in the legislative reforms and in the Instructions of the State Attorney General's Office in recent years”.

In short, for this task of promoting the creation of case law criteria that overcome inequalities and their application in all court bodies, to which we referred earlier, to be successful and, therefore, to be taken on by the courts, it is essential that legal specialisation - criminal and extra-criminal - and in matters outside the law, but connected with the specialist field, and even dialectic (basic for the presentation, orally or in writing, of our arguments in a reasoned manner against those of the other parties, given the role played by the principle of contradiction in our Procedural Law[10]), is essential.

Although the process had begun earlier, it was from 2007 onwards that specialisation gained significant traction at the Public Prosecutor's Office to the point that the objective was set for it to form a substantial part of its organisational structure.

As stated in the Explanatory Memorandum to Law 24/2007, of 9 October, amending the Organic By-laws of the Public Prosecutor's Office, “in order to achieve greater efficiency in the actions of the Public Prosecutor's Office, the decision has been taken to give greater impetus to the principle of specialisation as a response to the new types of offences that have emerged in recent times. (...)

2. ROAD SAFETY COORDINATION PROSECUTOR. STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S ROAD SAFETY UNIT

As a result of this specialisation, the specialist Units of the State Prosecutor's Office have been created, each headed by a Prosecutor, as well as the specialised sections in each Prosecutor's Office, as we shall see.

Law 24/2007, as is clear from its content and Statement of Reasons, sought to reinforce the autonomy of the Public Prosecutor's Office, its reorganisation in accordance with the State of the Autonomous Regions - reorganising its geographical location - and its specialisation. With regard to the latter, which is what is of interest in this paper, the aim was for the Public Prosecutor's Office to have the same degree of specialisation in any part of Spain.

The Statement of Reasons points out that another of the new developments was the creation of the State Attorney General's Delegate Prosecutors, thereby relieving the Attorney General of tasks and facilitating the assumption by these Delegate Prosecutors of responsibilities in matters of coordination and the issuing of criteria through the proposal to the Attorney General of circulars or instructions that they consider necessary, a task which, from the point of view of unity of action, is better covered given their degree of specialisation and experience.

This reform rewords, among others, Articles 20 and 22.3 of the Organic By-Laws of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Article 20(3) shall read as follows:

“There shall also be, in the State Attorney General's Office, Specialist Prosecutors responsible for the coordination and supervision of the activity of the Public Prosecutor's Office (...) as regards other matters in which the Government, at the proposal of the Minister of Justice, having heard the State Attorney General, and subject to a report, in any case, from the Public Prosecutor's Council, considers it necessary to create such posts. The aforementioned Prosecutors shall have powers and exercise functions similar to those provided for in the preceding sections of this article, within the scope of their respective specialities, as well as those that may be delegated to them by the State Attorney General, all notwithstanding the powers of the Chief Prosecutors of the respective regional bodies".

In fact, as regards the specialist Prosecutors it is possible to distinguish between Deputy Prosecutors and Coordinating Prosecutors[11].

As indicated in State Attorney General Instruction No. 1/2015, on matters regarding the functions of the Coordinating Prosecutors and Deputy Prosecutors, "following the 2007 reform, the specific area of action of the Coordinating Prosecutors is regulated in Art. 20 of the EOMF, which expressly refers to the Prosecutor for Violence against Women, the Prosecutor for the Environment and the Prosecutor for Minors. Art. 20.3 of the EOMF leaves open the possibility of creating other posts for Coordinating Prosecutors". The post of Road Safety Prosecutor should be placed within the scope of Article 20.3 of the EOMF. “Alongside the Coordinating Prosecutors are the Deputy Prosecutors, whose legal framework consists of the provisions of section three of Article 22 of the EOMF, according to which the State Attorney General may delegate functions related to matters within their competence to Prosecutors.

Royal Decree 709/2006, of 9 June, which establishes the staffing structure of the Public Prosecutor's Office for 2006, creates the post of Coordinating Prosecutor for Road Safety, together the post of Coordinating Prosecutor for Alien Affairs. As the Statement of Reasons indicates, this is an area in which the sensitivity of Spanish society has increased considerably “taking into account, on the one hand, that certain unlawful conducts related to the traffic and circulation of motor vehicles are worthy of criminal treatment and, consequently, of public prosecution, especially when such elementary rights as the life or physical integrity of persons or damage to property are violated”.

State Attorney General Instruction No. 11/2005, of 10 November, on the effective implementation of the principle of unity of action established in Article 124 of the Spanish Constitution, deals with the figure and functions of the State Attorney General's Delegate Prosecutors in certain matters, but does not refer to the position of the Road Safety Coordinator Prosecutor, which had not yet been created.

State Attorney General Instruction No. 5/2007 on the Workplace Accident, Road Safety and Foreign Affairs Coordinator Prosecutor and on the respective sections of the regional prosecutor's offices, will address questions on the organisation and operation of the speciality of Road Safety, as well as two other specialities (Workplace Accidents and Foreign Affairs). Among other aspects, it analyses the relations between the Coordinating Prosecutor, the specialist Delegates in each territory and the Chief Prosecutors of each prosecutor's office.

As indicated in the aforementioned Instruction, "the unification of criteria for action in the repression of criminal road traffic offences must constitute an effective mechanism for the correct exercise of the prosecutorial function, seeking a proportionate, dissuasive and effective response to this crime which, due to the very serious consequences it causes, cannot be devalued by a certain feeling of impunity, relaxation in the profiling of criminal offences, or the adoption of restrictive criteria in the classification of certain conducts committed in its sphere".

3. FUNCTIONS OF THE ROAD SAFETY COORDINATING PROSECUTOR

State Attorney General Instruction no. 11/2005[12], as indicated, did not include road safety among the specialised areas, although it was referred to in Instruction 5/2007, on Prosecutors responsible for Coordinating Workplace Accidents, Road Safety and Alien Affairs and on the respective Sections of the Regional Prosecutor's Offices.

However, section V of State Attorney General Instruction no. 11/2005 establishes a series of general provisions aimed at specialist Prosecutors, which are also applicable to the Prosecutor for Road Safety Coordination (Instruction 5/2007, section III).

New functions deriving from State Attorney General Instruction no. 1/2015 must also be added, without forgetting Circular 10/2011, of 17 November, on criteria for the specialised action unit of the Public Prosecutor's Office in matters of Road Safety.

The functions can be divided as follows:

A) Coordination functions

- Coordination and supervision of the specialised Sections of the Territorial Prosecutor's Offices, gathering the appropriate reports and guiding, by delegation of the State Attorney General, the Network of Specialised Prosecutors, as a forum for the exchange of information and dissemination of criteria for action throughout the national territory.

- Within these powers, it is worth highlighting the supervision of indictments and sentences handed down for crimes within the speciality resulting in homicides or particularly serious injuries, especially spinal cord and brain injuries, (generally crimes of homicide and reckless injuries), without prejudice to the fact that the Prosecutor of the Chamber may extend it to other reports, as well as the possibility, also included in the Instruction, that the regional Prosecutor's Offices may send other reports for examination due to their special social repercussion or legal transcendence.

In general, the acts of the Public Prosecutor's Office must comply, from a substantive perspective, with the necessary requirement of motivation (proportionate to the entity of the act) and from a formal perspective, with basic minimum requirements of neatness, clarity and intelligibility, which will benefit the prestige and credibility of the Institution (Instruction 1/2005, of 27 January, on the form of the acts of the Public Prosecutor's Office). This is all the more so in the case of written pleadings, given their importance in criminal proceedings.

This supervisory function is connected to the need to consolidate a system of individualised control and monitoring of particularly relevant cases handled by the specialisation.

This supervisory function must be extended to the knowledge and analysis of the court's response to the Prosecutor's claims (especially sentences), in order to be able to assess the sense and degree of coincidence of the response with the Prosecutor's requests and the possibility of lodging the corresponding appeals.

The exercise of this monitoring function shall be documented by the specialised unit in the form of monitoring files.

- In relation to the supervisory functions, to the event that a Coordinating or Deputy Prosecutor detects non-compliance in excess of the above, they will communicate this directly to the Prosecutorial Inspectorate, for the corresponding purposes. They may report aspects that should receive priority attention during inspections to the Inspectorate.

In turn, Senior Prosecutors and the Public Prosecutor's Inspectorate will inform the Coordinating Prosecutor of the problems and incidents detected in the course of the inspections carried out in relation to the specialist field.

- As an example of the dissemination of information among the members of the network, worth mention is the preparation of case law summaries on the subject by the Coordinating Prosecutor, which will be sent to all the Delegates of the specialist field. The regional delegates, in turn, must transfer the most significant resolutions on the matter to the specialised unit (Instruction 1/2015).

- Investigation of matters of special importance assigned to them by the State Attorney General, processing the corresponding investigative proceedings, participating directly (or through delegates) in the procedure at its different stages and bringing the appropriate actions. This is an exceptional possibility.

- As regards appeals, the Coordinating Prosecutors will inform the Prosecutors of the Supreme Court of any appeals for reversal which, in relation to the specialist field, are prepared by the regional Prosecutor's Offices and which, due to their content or technical-legal approach, require the appropriate coordination of criteria with the Supreme Court Prosecutor's Office. In any case, when the Supreme Court Prosecutors note that the position to be adopted by the Supreme Court Prosecutor's Office, when responding to an appeal lodged by the other parties, may contradict the criteria for action defined by the Road Safety Unit, they shall inform the Coordinating Prosecutor in order to jointly assess the application of these criteria (Instruction 5/2008).

B) Functions related to the unification of criteria

- Propose to the State Attorney General as many Circulars and Instructions as it deems necessary, as well as proposals for the resolution of Consultations that arise on matters within its remit. They shall also prepare the corresponding drafts of such Circulars, Instructions or resolutions of Consultations.

- Drafting of opinions[13].

The Public Prosecutor will directly resolve informal enquiries submitted to them on matters within their jurisdiction, informing the State Attorney General accordingly. Depending on the nature of the matter, the Coordinating Prosecutor may choose between issuing an opinion which will be sent to the State Attorney General or drawing up a draft resolution for consultation which will be sent to the State Attorney General.

In the opinions, it will set out its position in response to enquiries from a particular prosecutor's office, which will not be binding, but will be indicative. If it is considered necessary to make them binding, a proposal for an Instruction, Circular or Consultation should be filed.

C) Training

Instruction 5/2007 provides, on the one hand, that (with a view to developing criteria for the unification of actions among the Delegates and Sections) the Prosecutor should hold regular meetings, specialised courses, draw up a guide for the actions of these Prosecutors, and exchange, publish and disseminate the annual activities of the Road Safety Prosecutors. Furthermore, it must propose permanent training courses for Prosecutors on matters within their specialist field and intervene in the coordination of these courses.

The Organic By-Laws of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Public Prosecution Regulations (RMF) also refer to the training of Deputy Prosecutors. Article 22.3 of the Organic By-Laws of the Public Prosecutor’s Office states that "Prosecutors may (...) participate in determining the criteria for the training of specialist prosecutors".

In the same legal text, Art. 18.3 indicates, in relation to the sections, that preference will be given to those who have specialised in the subject due to previous functions performed or courses imparted or passed.

In turn, Article 62 of the RMF states that, with regard to the appointment and dismissal of Specialist Deputy Prosecutors, that "in order to fill these positions, preference will be given to having received specific training in the area of the speciality and having practical experience".

Instruction 1/2015 further clarifies these provisions.

With regard to the subjects covered by areas of specialisation, the opinion and suggestions of the Coordinating Prosecutor should be sought when planning initial and continuing training, as he is in the best position to identify training needs and to set priorities.

Likewise, the Coordinating Prosecutor should be taken into account when selecting teaching staff, taking into account the type of training that, in each case, is sought.

- Lead the speciality deputy prosecutor workshops, which must necessarily deal with new legislative developments and whose conclusions may constitute hermeneutical guidelines.

The joint analysis makes it possible to share experiences in relevant aspects such as the internal organisation of the service; the staff and material resources available; the relationship with other specialised services or with other bodies of the Public Prosecutor's Office itself; the mechanisms established for the identification, control and monitoring of cases, visas, control of sentences, participation in the preparation of appeals for reversal, etc., or relations with regional police forces or with other bodies or institutions.

The conclusions of the Delegate Prosecutor Workshops for the specialist field must be endorsed by the State Attorney General. Although they cannot be conceived as an indirect way of innovating the State Attorney General's doctrine (Circulars, Instructions and Consultations), they can constitute a guide, guidelines, hermeneutic directives that orient prosecutors and be the origin of criteria reflected in the State Attorney General's doctrine. They may also incorporate proposals for legislative reforms that are then included in the Report.

D) Participation in meetings

- Chairing, where appropriate, the Meetings of Chief Prosecutors that the Chief Prosecutor of the High Court of Justice may convene as the hierarchical superior to establish positions or maintain the unity of criteria on matters of the speciality in which the Delegates of the respective Sections participate.

- Participate in the meetings of Senior Public Prosecutors when issues relating to the speciality are discussed (Instruction 1/2015 in relation to Art. 16(2) of the EOMF).

E) Preparing a section of the Report

-Development of a specific section in the Annual Report by the State Attorney General in which the problems encountered in the field are analysed, to provide an overview of the evolution of the activity of the speciality throughout the national territory.

Consideration shall be given to Instruction 1/2014, on the reports of the bodies of the Public Prosecutor's Office and the State Prosecutor's Office.

F) Statistics

Adoption of measures aimed at improving statistics.

G) Proposed reforms of services

With a view to encouraging the active intervention of the Public Prosecutor's Office in the launch, investigation and subsequent follow-up of legal cases aimed at investigating the corresponding offences and ensuring a fluid relationship with the Administration.

H) Institutional

- General coordination in each of the corresponding areas, with the competent authorities and bodies of the different Administrations.

- Promote and participate in the adoption of Protocols and Agreements for coordination and collaboration with other bodies involved in the prevention, eradication and prosecution of crimes in this specialist field.

- Receive, answer and follow up on those letters sent to the State Attorney General by citizens, associations and institutions on matters within its remit.

The complexity of the specialist field requires an interdisciplinary approach to problems, which implies a relationship with different institutions, both public and private.

As can be seen, the functions of the Coordinating Prosecutor are wide and varied; nonetheless, all of them are aimed at what we indicated at the beginning, achieving unity of action in the Public Prosecutor's Office through specialisation, in the interests of the principles of equality and legal security in an area such as road safety in which, in short, the aim is to advance the barrier of protection of other legal assets such as the life, health and physical integrity of people.

4. SPECIALISED SECTIONS IN EACH REGIONAL PROSECUTOR'S OFFICE. DEPUTY PROSECUTORS

It is envisaged that the specialised Road Safety Section will be set up in all regional public prosecutors' offices, forming part of their organisational structure as units with specific tasks. Coordinated vertical specialisation, which occurs with the creation of the Coordinating Prosecutor, involves the creation of a Road Safety Section in each prosecutor's office. This is in line with a homogeneous system that may admit certain differences depending on the templates and the volume of the subject matter in each case. The latter will determine, e.g., whether the members of these sections take on the function exclusively or not[14] and the number of prosecutors in these sections[15].

"In general terms, specialised Sections can be defined as units within each Public Prosecutor's Office which, bringing together a series of staff and material resources, are organised in response to the need to specialise the intervention of the Public Prosecutor's Office in certain matters" (Instruction 5/2008).

At a provincial level, changes are introduced in order to strengthen the specialisation of the Public Prosecutor’s Office through the specialised sections in each Provincial Prosecutor's Office. Thus, Art. 18.3(2) and (3), Organic By-Laws of the Public Prosecutor’s Office states that “these Prosecutor's Offices may have specialised Sections in those matters which are determined by law or regulation, or which, due to their singularity or the volume of proceedings they generate, require a specific organisation. These Sections may be set up, if deemed necessary for their proper functioning according to their size, under the direction of a Senior Prosecutor, and one or more Prosecutors belonging to the staff of the Prosecutor's Office will be assigned to them, with preference being given to those who, due to previous functions performed, courses imparted or passed or any other similar circumstance, have specialised in the field. However, when the needs of the service so require, they may also act in other areas or fields.

The Sections shall exercise the functions attributed to them by the respective Chief Prosecutors, within the scope of the matter that corresponds to them, pursuant to the provisions of these By-Laws, the implementing regulations and the Instructions of the State Attorney General. (...). The instructions given to the specialised Sections in the different Prosecutor's Offices, when they affect a specific regional area, shall be communicated to the High Prosecutor of the corresponding Autonomous Community”.

One of the areas in which there is a section in each provincial prosecutor's office is road safety[16]. This precept establishes the structure that, where appropriate, may be set up: a Delegate (who may be the Dean[17]), who will direct it, and the prosecutors assigned to it.

Furthermore, as we have indicated, preference for training sections is given to those who have specialised in the subject either because they have experience in the field (based on the functions they have performed previously) or because they have imparted or passed courses. Developing on the latter, Article 62 of the Organic Public Prosecutor Regulations (ROMF), in relation to the appointment and dismissal of Deputy Prosecutors at Special Prosecutor's Offices and Deputy Specialist Prosecutors, states that with regard to "Deputy Specialist Prosecutors: (...) In order to fill these posts, preference will be given to having received specific training in the subject matter in question and having practical experience".

However, specialisation is being strengthened not only at a provincial level, but also at the level of the autonomous regions. In this sense, Art. 18.3, paragraph 6, indicates that “these Sections may be constituted in the Public Prosecutor's Offices of the Autonomous Communities when their competences, the volume of work or the better organisation and provision of the service make this advisable”.

The Deputy of the specialist area for the Autonomous Community will be responsible for liaising and coordinating with the specialist Prosecutors of the Autonomous Community and liaison with the Coordinating Prosecutor (Instruction 1/2015).

"In the case of regional Deputy Specialist Prosecutors, the position will be filled by a provincial Delegate Specialist in the autonomous community" (Article 62 ROMF).

With regard to appointment, "the specialist delegate prosecutors, both regional and provincial, will be appointed and, where appropriate, relieved, by Decree issued by the head of the State Attorney General's Office, at the proposal of the respective Chief Prosecutor and following a report by the Specialist or Delegate Prosecutor.

The Chief Prosecutor will fill the deputy specialist vacancy from the prosecutors on staff.

The proposal for appointment of the Chief Public Prosecutor shall be reasoned and shall be accompanied by a list of all the prosecutors who have applied for the post, together with their merits. Once received by the Public Prosecutor's Inspectorate, it will be transferred it to the respective Prosecutor of the Chamber, who may make such considerations as they deem appropriate, and the head of the Public Prosecutor's Office will then take a decision, after hearing the Public Prosecutor's Council" (Art. 62.2 RMF).

The Chief Prosecutor shall formalise the delegation of management and coordination functions in writing. The delegation document shall expressly state the functions related to Road Safety to be delegated, which shall be related to management or coordination activities compatible with the supervisory responsibility of the Chief Prosecutor, based on the principle of making the Section more efficient and taking into account its specialist nature.

The Chief Prosecutors may entrust the Road Safety Deputies with management and coordination functions, including but not limited to:

a) Coordination, distribution of work, and allocation of services among the specialist prosecutors assigned to the Section.

b) Relations with the Delegates of other Sections, and with the Coordinators of the other Services of the Public Prosecutor's Office and of the Permanent Attachments, as well as with the Delegates of the same specialisation at other Public Prosecutor's Offices.

c) The organisation of the Section's records.

d) The organisation and distribution of work of the auxiliary staff assigned to the Section.

e) The preparation of studies to improve the service provided by the Section or on technical issues arising from the application of regulations.

f) The production of statistical reports relating to the Section.

g) Control of the removal of indictments in proceedings relating to special matters.

h) Endorsement of reports, applications for a stay of proceedings and reports.

i) Endorsement of expert opinions involving the specialisation in question.

j) The control of judgements and the endorsement of appeals in the field of the speciality.

k) The supervision of criminal cases on matters of the speciality with defendants subject to the precautionary measure of imprisonment and the subsequent approval or knowledge of requests for release or imprisonment.

l) The drafting of the section of the Report relating to the Section.

The reports by the specialised Sections as part of the preparation of the Report will include a point referring to issues and questions which, because they have not been sufficiently resolved, are considered as being potentially subject to a ruling by the Coordinating Prosecutor of the specialisation, either by means of an Opinion or through a Circular, Instruction or Consultation.

m) Coordination with the Authorities, Services, Entities and Organisms related to activities linked to the subject of the speciality.

n) Reporting to the Coordinating Prosecutor of the facts relating to the matter of the speciality that may merit the consideration "of special importance" for the purposes of its possible direct intervention.

o) Being the spokesperson for the Public Prosecutor's Office before the media in the field of the specialisation under the direction of the Chief Public Prosecutor.

The Deputy may not in delegate the powers delegated to them by the Chief Prosecutor, unless with their authorisation and for specific tasks.

In the event that the Coordinating Prosecutor disagrees with the Chief Prosecutor of a Prosecutor's Office and the Deputy on the criteria to be adopted in ongoing proceedings, they shall present the circumstances to the State Attorney General for the appropriate decision to be taken.

Functions of the Road Safety Sections:

The Road Safety Sections, which in no case will directly assume the handling of these specialised cases, given the enormous volume of these cases.

The functions of this Section shall essentially be as follows:

1) Inform the Prosecutors of the guidelines for action on road safety generated by the General State Prosecutor's Office and by the Coordinating Prosecutor.

2) They will be directly responsible for handling the most important or complex cases relating to road safety, when the Chief Prosecutor so determines.

3) Oversee the monitoring of the unified road safety performance standards achieved.

4) When delegated by the Chief Prosecutor, they shall be responsible for drafting the annual report on road safety, to be included in the Annual Report.

5) When delegated by the Chief Prosecutor, they will be responsible for holding the appropriate periodic meetings with governmental authorities with responsibility for the matter, the Civil Traffic Guard and Autonomous and Local Police in relation to offences related to road safety. Also, when delegated by the Chief Prosecutor, they will hold meetings and be in contact with Victims' Associations.

6) Maintain at a regional level, when delegated by the Chief Prosecutor, the necessary collaboration and participation with public and private services and entities whose function is to promote, guarantee and investigate road safety.

7) Take action to ensure the rights of victims of road violence.

8) Promote due compliance with inter-institutional communications relating to its functional area (the Instructions of the State Attorney General's Office 4/1991 of 13 June, 2/1999 of 17 May and 1/2003 of 7 April indicate that when a dismissal is requested or an acquittal is handed down in proceedings for driving under the influence of alcohol, the Court should be asked to notify the Provincial Traffic Headquarters of the relevant resolution in case the conduct deserves to be prosecuted as an administrative offence).

9) Forward indictments, reports, testimonies of proceedings, judgements and appeals on the matter considered as being of particular importance to the Prosecutor.

10) Participate in the meetings held periodically with the Coordinating Prosecutor with a view to unifying criteria.

11) Draw up a six-monthly report to be sent to the Coordinating Prosecutor, which shall include six-monthly statistics, meetings held with authorities and social agents, reference to matters of greater importance or complexity and any substantive, procedural or organisational issues or problems that may arise.

12) When delegated by the Chief Prosecutor, assume responsibility for keeping the Section’s registers.

13) Inform the Road Safety Coordinating Prosecutor of any proceedings or procedures that may be considered to be of “special importance” for the purposes of its possible direct intervention.

Area Prosecutor's Offices:

The functions of the regional deputy for each speciality have a provincial nature.

To this end, coordination mechanisms must be established to allow the Deputy Prosecutor to extend their activity as Deputy to the Area Prosecutor's Offices (when the Deputy is based at the Provincial Prosecutor's Office) or to the Provincial Prosecutor's Office and the other Area Prosecutor's Offices, for cases in which, exceptionally, the Deputy is based in an Area Prosecutor's Office.

To this end, liaison prosecutors should be appointed to liaise with the Provincial Deputy of the speciality for bodies of the Public Prosecutor's Office where the Deputy is not located, i.e. normally in the Area Prosecutor's Office.

5. STATISTICS. 2023 STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL REPORT AND 2022 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT ROAD ACCIDENT BALANCE SHEET

The 2023 Annual Report of the State Prosecutor's Office includes statistical data corresponding to 2022. Below is a summary of the figures on road safety.

The Report begins with a presentation of the provisional balance of road accidents in 2022, the first year in which mobility returned to normal after the traffic restrictions imposed during the pandemic[18]. The provisional data published by the Department for Traffic, referring only to interurban roads and victims registered up to 24 hours after the accident, quantified the number of fatal accidents at 1,145 people, 44 more than in 2019, up by 4%. Furthermore, 4,008 people were seriously injured, 425 less than in 2019, a decrease of 10%.

However, the figures are different in the Balance of road accident figures 2022, published in June 2023 by the Department for Traffic[19]. These figures include immediate fatalities or those occurring within 30 days of the crash and casualties on both urban and interurban roads. Only the data for Catalonia are provisional. In 2022, 1,746 people died on our roads, compared to 1,755 in 2019, a decrease of 0.51%. On the other hand, 8,503 people were seriously injured, compared to 8,613 in 2019[20], a decrease of 1.2%.

This implies a death rate per million residents of 37 - 32 in 2021 and 37 in 2019. This places Spain in sixth among EU countries, with an average of 46[21].

The following table shows the number of deaths per million inhabitants. 1993-2021.

|

Years |

Death rate |

|

1993 |

162 |

|

1994 |

142 |

|

1995 |

145 |

|

1996 |

138 |

|

1997 |

140 |

|

1998 |

148 |

|

1999 |

142 |

|

2000 |

143 |

|

2001 |

136 |

|

2002 |

130 |

|

2003 |

129 |

|

2004 |

111 |

|

2005 |

103 |

|

2006 |

93 |

|

2007 |

85 |

|

2008 |

68 |

|

2009 |

59 |

|

2010 |

53 |

|

2011 |

44 |

|

2012 |

41 |

|

2013 |

36 |

|

2014 |

36 |

|

2015 |

36 |

|

2016 |

39 |

|

2017 |

39 |

|

2018 |

39 |

|

2019 |

37 |

|

2020 |

29 |

|

2021 |

32 |

|

2022 |

37 |

The following table shows the number of deaths per million inhabitants. European Union, 2022.

|

Country |

Death rate |

|

Sweden |

22 |

|

Denmark |

26 |

|

Ireland |

31 |

|

Germany |

33 |

|

Finland |

34 |

|

Spain |

37 |

|

Estonia |

38 |

|

Slovenia |

40 |

|

Austria |

41 |

|

Cyprus |

41 |

|

The Netherlands |

42 |

|

Lithuania |

43 |

|

Belgium |

45 |

|

Slovakia |

45 |

|

France |

48 |

|

Malta |

50 |

|

Czech Republic |

50 |

|

Poland |

50 |

|

Italy |

54 |

|

Hungary |

55 |

|

Luxembourg |

56 |

|

Latvia |

60 |

|

Greece |

61 |

|

Portugal |

62 |

|

Croatia |

71 |

|

Bulgaria |

78 |

|

Romania |

86 |

|

EU-27 |

46 |

The number of people killed on interurban roads increased compared to 2019 (1,270 compared to 1,236) in contrast to the decrease on urban roads: 476 deaths compared to 519 in 2019[22].

The following table shows the number of casualties on interurban roads. 2013-2022.

|

Year |

Total |

Deceased persons |

Injured persons requiring hospital treatment |

Injured persons not requiring hospital treatment |

|

2013 |

57,732 |

1,230 |

5,182 |

51,320 |

|

2014 |

54,774 |

1,247 |

4,834 |

48,693 |

|

2015 |

54,028 |

1,248 |

4,744 |

48,036 |

|

2016 |

57,720 |

1,291 |

5,050 |

51,379 |

|

2017 |

58,427 |

1,321 |

4,766 |

52,340 |

|

2018 |

58,892 |

1,317 |

4,451 |

53,124 |

|

2019 |

56,946 |

1,236 |

4,303 |

51,407 |

|

2020 |

38,582 |

975 |

3,361 |

34,246 |

|

2021 |

47,399 |

1,116 |

3,642 |

42,641 |

|

2022 |

49,623 |

1,270 |

3,897 |

44,456 |

The following table shows the number of casualties on urban roads. 2013-2022.

|

Year |

Total |

Deceased persons |

Injured persons requiring hospital treatment |

Injured persons not requiring hospital treatment |

|

2013 |

68,668 |

450 |

4,904 |

63,314 |

|

2014 |

73,546 |

441 |

4,740 |

68,365 |

|

2015 |

82,116 |

441 |

4,751 |

76,924 |

|

2016 |

84,480 |

519 |

4,705 |

79,256 |

|

2017 |

82,565 |

509 |

4,780 |

77,276 |

|

2018 |

81,523 |

489 |

4,484 |

76,550 |

|

2019 |

84,167 |

519 |

4,310 |

79,338 |

|

2020 |

57,350 |

395 |

3,320 |

53,635 |

|

2021 |

72,296 |

417 |

4,142 |

67,737 |

|

2022 |

79,980 |

476 |

4,606 |

74,898 |

In 2023, the provisional figures for fatalities within 24 hours on interurban roads in summer are as follows[23].

Between 1 July and 31 August 2023, a total of 234 people were killed and 946 people injured were hospitalised.

These numbers show a 3% increase in the number of people killed compared to the same period in 2022. Compared to 2019, there is a 9% increase in the number of deaths. In terms of injured persons requiring hospital treatment, there is an increase of 13% compared to 2022 and 6% compared to 2019.

The slight decrease in the accident rate for 2022 is in contrast to the data provided by the court statistics on road crime - road safety offences. These figures have increased again for all indicators in 2022, the highest in recent years, with percentage increases of between 20% and 30% (depending on the indicator) compared to 2019. There are therefore road crime figures that are not connected to mobility and road accident data.

Road safety offences (Arts. 379 to 385 Criminal Code) in 2022 saw a new and significant increase in court proceedings, indictments and convictions, which were again well above not only the pre-pandemic figures of 2019 and previous years, but also those of 2021 in which the figures for road crime were notably high. In 2022, the volume of indictments and convictions were the highest on record since the reform carried out under Organic Law 15/2007, and the same goes, as we will analyse below, for the number of proceedings initiated.

These court figures from 2022, the first year with in which mobility returned to normal after Covid-19, seem to indicate a change in our driving habits after the pandemic. This has resulted in a notable increase in traffic crime in our country, as a consequence of a consequent loss of the necessary road awareness that citizens had acquired in recent years.

In 2022, 137,406 proceedings were initiated in Spain for road safety offences under Art. 379 to 385 of the Criminal Code, an overall increase of 11,400 proceedings and a percentage increase of 9.1% compared to 2021 (which already saw an increase of 9.8% compared to 2019). The volume of court activity in the field of road offences is the highest from the past decade and dating back to 2005, only surpassed by the 140,650 proceedings filed in 2011.

The proceedings initiated, as Preliminary or Urgent Proceedings, for offences in relation road safety and their evolution, since 2012, is reflected below:

|

Preliminary Proceedings + Urgent Proceedings |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

Art.379.1 Criminal Code |

1,021 |

752 |

818 |

902 |

813 |

842 |

889 |

1,562 |

1,193 |

1,111 |

|

Art.379.2 Criminal Code |

72,430 |

69,340 |

61,346 |

61,177 |

59,466 |

69,121 |

68,039 |

57,262 |

70,674 |

77,133 |

|

Art. 380 Criminal Code |

2,587 |

2,384 |

2,310 |

2,658 |

2,761 |

1,553 |

2,009 |

3,050 |

3,360 |

3,539 |

|

Art. 381 Criminal Code |

318 |

204 |

190 |

204 |

190 |

87 |

207 |

297 |

268 |

267 |

|

Art. 383 Criminal Code |

2,070 |

1,884 |

1,550 |

1,583 |

1,819 |

2,013 |

2,381 |

2,252 |

2,897 |

3,261 |

|

Art. 384 Criminal Code |

36,017 |

33,883 |

31,231 |

31,262 |

30,875 |

36,649 |

40,670 |

37,172 |

47,058 |

51,431 |

|

Art. 385 Criminal Code |

411 |

396 |

482 |

417 |

379 |

389 |

477 |

489 |

489 |

664 |

|

OVERALL |

114,854 |

108,843 |

97,927 |

98,203 |

96,303 |

110,654 |

114,672 |

102,084 |

125,939 |

137,406 |

In 2022, 105,078 indictments were brought by the Public Prosecutor's Office for dangerous road offences, just over 34% of the total number of indictments brought by the Public Prosecutor's Office for all types of prosecutions for all offences (the highest comparative percentage in the last six years).

In the same year, 104,660 convictions were handed down for road safety offences under Arts. 379-385 of the Criminal Code, more than 36% of all those pronounced by the Courts for all kinds of offences (also the highest comparative percentage of the last six years). Of these, 59,461 convictions were for driving under the influence of alcohol and drugs (4,697 convictions more than in 2021, up by 8.5%), the highest number of convictions for this offence since 2012, and 38,383 for driving without a licence (4,256 more than in 2021, up by 12.4%), the highest figure for this offence in the last decade.

Indictments and convictions over the past three years are reflected in this table:

|

Comparison 2020-2022 |

Public prosecution accusations in 2020 |

Sentences in 2020 |

Public prosecution accusations in 2021 |

Sentences in 2021 |

Public prosecution accusations in 2022 |

Sentences in 2022 |

|

379.1 Criminal Code |

707 |

391 |

733 |

578 |

644 |

569 |

|

379.2 Criminal Code |

39,485 |

38,241 |

53,298 |

54,764 |

58,041 |

59,461 |

|

380 Criminal Code |

1,918 |

1,433 |

2,246 |

1,928 |

2,222 |

2,12 |

|

381 Criminal Code |

169 |

82 |

154 |

138 |

182 |

114 |

|

383 Criminal Code |

2,482 |

2,301 |

3,401 |

3,382 |

5,16 |

3,967 |

|

384 Criminal Code |

26,807 |

24,156 |

36,367 |

34,127 |

38,787 |

38,383 |

|

385 Criminal Code |

45 |

44 |

45 |

25 |

42 |

46 |

|

OVERALL |

71,613 |

66,648 |

96,244 |

94,942 |

105,078 |

104,66 |

With this in mind, more than one third of criminal charges and convictions in Spain were for dangerous road offences.

Both the number of indictments and the number of convictions in 2022 have seen extraordinary increases, both in relation to the previous year (when the figures were already remarkably high) and the pre-pandemic period. Thus, approximately 8,800 more indictments have been brought in 2022 than in 2021 (a percentage increase of 9.1%) and approximately 9,700 more convictions have been handed down than in 2021 (a percentage increase of 10.2%). It is worth noting that the volume of indictments and convictions in 2022 is the highest on record, with the number of indictments exceeding 103,853 in 2009 and convictions exceeding 100,000, which has not been the case at least since the major reform of 2007.

An estimated 90% of the total of 104,660 convictions were handed down without dispute, allowing for the almost immediate execution of the 66,231 disqualifications from driving and 1,612 loss of driving licence under Art. 47.3 of the Criminal Code this year, and the prompt execution of a large part of the estimated 76,000 fines and 25,485 community service sentences also imposed in 2022.

Finally, below, details are provided of the investigation proceedings of the Public Prosecutor's Office for dangerous road offences within the framework of Art. 5 of the EOMF. Thus, in 2022, 670 proceedings were initiated for road safety offences under Arts. 379-385, the vast majority (specifically 621) for driving without a licence under Art. 384 of the Criminal Code, continuing the downward trend noted in previous years which, according to a number of Deputy Prosecutors, may be due to better coordination between Provincial Headquarters, Traffic Police, Public Prosecutor's Office and Courts.

In terms of positive resolution rates, the already high percentage of proceedings ending in conviction continued to rise in 2022, with approximately three out of every four proceedings initiated seeing a sentence handed down (76%, with a percentage increase of 1% compared to 2021). When adding the number of convictions to the number of acquittals and dismissals, the resolution rates would be practically the same between proceedings initiated and those resolved, consolidating the speed, efficiency, interpretative uniformity and legal certainty of criminal traffic justice in Spain.

The table below shows the so-called positive resolution rates, i.e. the ratio between the number of cases resolved by conviction and the number of proceedings initiated, as well as year-on-year changes:

|

CRIMES CSV |

Preliminary Proceedings+Urgent Proceedings 2022 |

Sentences in 2022 |

Resolution rate 2022 |

Resolution rate 2021 |

|

379.1 Criminal Code |

1,111 |

569 |

0.51 (51%) |

0.48 |

|

379.2 Criminal Code |

77,133 |

59,461 |

0.77 (77%) |

0.77 |

|

380 Criminal Code |

3,539 |

2,12 |

0.59 (59%) |

0.57 |

|

381 Criminal Code |

267 |

114 |

0.42 (42%) |

0.51 |

|

383 Criminal Code |

3,261 |

3,967 |

1.21 (121%) |

1.16 |

|

384 Criminal Code |

51,431 |

38,383 |

0.74 (74%) |

0.72 |

|

385 Criminal Code |

664 |

46 |

0.06 (6%) |

0.05 |

|

OVERALL |

137,406 |

104,66 |

0.76 (76%) |

0.75 |

In 2022, more than 73% (almost three out of four, up by 2.4% compared to 2021) of the proceedings initiated and 82% (approximately four out of five, a percentage increase of 2.7% compared to 2021) of the charges brought for dangerous road traffic offences were brought through the fast-track trial procedure. This consolidates the overcoming of anomalies seen during the pandemic and reinforces the traditional speed of the criminal response to road traffic crime in Spain.

This is reflected in the following table:

|

ROAD CRIMES |

Preliminary Proceedings |

Urgent Proceedings |

Total |

|

Proceedings Initiated |

37,059 |

100,347 |

137,406 |

|

Indictments Brought |

18,113 |

86,965 |

105,078 |

In 2022, the volume of convictions rose across the board in all territories, with the exception of Catalonia, with around 900 fewer convictions, Aragon and La Rioja. The largest increases in absolute terms occurred, in this order, in Madrid, with almost 5,000 more convictions than in 2021, Valencia, Andalusia and the Canary Islands, the latter three Autonomous Communities with approximately 1,000 more sentences than in the previous year. However, despite these slight fluctuations, the regional distribution of convictions by Autonomous Community remains practically identical, with Catalonia, despite the aforementioned reduction, maintaining its traditional first place, followed by Andalusia and Madrid, which climbs one place, above the Region of Valencia, which drops to fourth.

The following table shows the regional distribution of convictions and their evolution 2020-2021:

|

Autonomous communities |

379.1 Criminal Code |

379.2 Criminal Code |

380 Criminal Code |

381 Criminal Code |

383 Criminal Code |

384 Criminal Code |

385 Criminal Code |

TOTAL 2022 |

CHANGE |

|

Andalusia |

67 |

9,324 |

517 |

33 |

492 |

7,964 |

3 |

18,400 (17,313). |

+1,087 |

|

Aragon |

13 |

841 |

23 |

0 |

28 |

606 |

3 |

1,514 (1,652). |

-138 |

|

Asturias |

3 |

1,311 |

48 |

0 |

69 |

595 |

1 |

2,027 (1,831). |

+196 |

|

Balearic Islands |

12 |

2,229 |

52 |

0 |

148 |

1,183 |

2 |

3,626 (3,218). |

+408 |

|

Canary Islands |

25 |

2,767 |

59 |

9 |

318 |

2,285 |

0 |

5,463 (4,457). |

+1,006 |

|

Cantabria |

5 |

758 |

44 |

3 |

33 |

489 |

1 |

1,333 (1,109). |

+224 |

|

Catalonia |

135 |

9,899 |

315 |

23 |

814 |

7,316 |

4 |

18,506 (19,407). |

-901 |

|

Extremadura |

8 |

1,012 |

59 |

2 |

43 |

506 |

2 |

1,632 (1,603). |

+29 |

|

Galicia |

36 |

3,645 |

110 |

2 |

227 |

2,425 |

1 |

6,446 (5,804). |

+642 |

|

La Rioja |

3 |

330 |

25 |

0 |

27 |

219 |

2 |

606 (635). |

-29 |

|

Madrid |

94 |

9,732 |

229 |

10 |

576 |

4,967 |

2 |

15,610 (10,631). |

+4,979 |

|

Murcia |

7 |

2,284 |

82 |

5 |

143 |

1,486 |

0 |

4,007 (3,896). |

+111 |

|

Navarre |

9 |

915 |

30 |

0 |

42 |

381 |

1 |

1,378 (1,210). |

+168 |

|

Basque Country |

11 |

2,297 |

86 |

11 |

195 |

951 |

5 |

3,556 (3,443). |

+113 |

|

Region of Valencia |

88 |

7,570 |

266 |

8 |

564 |

3,875 |

2 |

12,373 (11,059). |

+1,314 |

|

Castilla-La Mancha |

15 |

2,120 |

62 |

5 |

107 |

1,514 |

15 |

3,838 (3,723). |

+115 |

|

Castilla-Leon |

38 |

2,427 |

113 |

3 |

141 |

1,621 |

2 |

4,345 (3,951). |

+394 |

|

Total sentences |

569 |

59,461 |

2,120 |

114 |

3,967 |

38,383 |

46 |

104,660 |

|

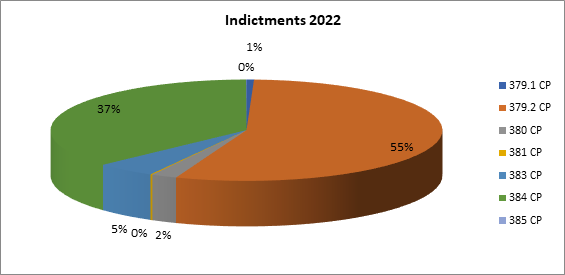

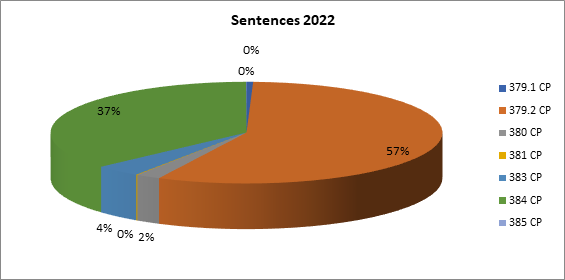

The graphical representation of the statistical data (indictments and convictions) is as follows:

Table 1. Indictments for criminal offences

Table 2. Convictions for offences

These statistics for 2022, analysed above, allow us to draw the conclusion that from a quantitative perspective, the weight of this speciality deserves to be addressed through specialisation. On the other hand, from a qualitative perspective, the legal assets that are ultimately at stake, either directly (crimes of result) or indirectly (crimes of endangerment), are of the highest level.

6. 2030 ROAD SAFETY STRATEGY

The Road Safety Strategy[24] sets out a general roadmap that guides institutional actions on road safety in the coming years. This document connects to the previous 2011-2020 Strategy and serves as a national reference framework for road safety policy in our country in the 2030 horizon.

The 2030 Road Safety Strategy is the result of a reflection process involving three areas:

Firstly, internally, at the Department of Traffic, entailing an assessment of the previous strategy and of the current road safety situation and future forecasts.

As well as the analysis of the most relevant international strategies and resolutions, with a view to remaining aligned with the most current and efficient trends and proposals.

And finally, a process of shared reflection with the main road safety stakeholders in our country, both from the different public administrations and from civil society. This process has been led by the Superior Council for Traffic, Road Safety and Sustainable Mobility[25].

The two main objectives of the 2011-2020 Strategy were to lower the death rate to 37 deaths per million inhabitants and to reduce the number of people seriously injured by 35%. The targets achieved represent a 37.3% drop in the annual death rate per million inhabitants and a 38.1% reduction in the number of seriously injured people[26].

The document, in analysing the current road accident situation in our country, highlights that the most frequent causes of accidents were distractions (28%), driving under the influence of alcohol[27] or drugs[28] (25%) and speeding (23%)[29]. Furthermore, vulnerable groups and means of transport (pedestrians, bicycles, motorbikes) accounted for 53% of the total number of fatalities, the first time they have exceeded 50% on record. One in four fatalities was a motorbike rider; and 82% of all those killed on urban roads were vulnerable[30].

National road safety policies need to be understood within an international context[31] to support and align their objectives.

In 2015, the UN included road safety in the 2030 Agenda as one of the main health and development issues to be addressed through the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

A key milestone in addressing road safety for the next decade was the 3rd Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety, organised by the WHO in Stockholm in February 2020.

The UN's commitment to road safety has been updated in the resolution on Improving Global Road Safety, which proclaims the 2021-2030 period as the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety, with a view to reducing road traffic deaths and injuries by at least 50% during this period. As a result of this declaration, the WHO published the 2021-2030 Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety.

The European Union also recognises the need to continue the road safety improvement efforts made from 2011 to 2020. This was reflected in the 2017 Valletta Declaration, in which EU member states committed to following up with the ultimate goal of achieving Vision Zero by 2050, but with achievable targets over the next decade (2021-2030). In particular, the reduction by half of the number of people killed and seriously injured as a result of road accidents is presented as the main objective for 2030.

The European Commission's work to define the framework for road safety in Europe for the next decade was set out in the document: EU Road Safety Policy Framework 2021-2030. Next Steps towards 'Vision Zero'.

The Road Safety Strategy endorses the two main objectives proposed by the UN and the European Commission:

By 2030, reduce the number of people killed by 50% compared to the 2019 baseline (1,755).

By 2030, reduce the number of seriously injured people by 50% from the 2019 baseline (8,613)[32].

These general objectives are further developed into specific objectives in chapter 7. With a view to implementing the policies outlined in this chapter, nine major strategic areas are set out, which are developed along various lines of action.

Within the strategic area "Zero tolerance for high-risk behaviour", one of the lines of action is "Updating the criminal framework and strengthening the fight against traffic offences". The first objective in this line is to update and implement the criminal law framework, in order to improve the fight against trafficking offences and to improve the protection of victims under criminal law.

Also in this area, procedures for the detection of pre-crash mobile phone use and the investigation of driving under the influence of illegal drugs will be improved. Dissemination of information on the location of police checkpoints will continue to be tackled.

During the life of the Strategy, an analysis will be performed on the impact on the criminal investigation of the availability of data collected by the various vehicle safety systems, in particular the new data recording systems (EDR): Event Data Recorder, colloquially known as "black box") which will be mandatory for all vehicles from 2024 (categories M1 and N1) and 2029 (all other categories).

The Department of Traffic will continue, in collaboration with law enforcement officers, the plan to monitor driving without a licence that has already been deployed through the Provincial Traffic Headquarters[33].

Within the strategic area "Effective and fair response to accidents", one of the lines of action is "Reducing response times and improving assistance in the event of an accident".

The main objective in this respect should be the reduction of response times ("golden hour" or, now, "golden minutes"). These times can be divided into two parts. Firstly, the time taken to notify the emergency services. Secondly, the arrival times of the emergency services, on-site victim care and transfer to the hospital.

Another line of action in this strategic area is “Guaranteeing the rights of traffic victims”.

Long-term care must go beyond health care, as the after-effects of an accident on the victims and their immediate environment have an impact on many other factors, including but not limited to personal, family, social and work-related.

In this area, a variety of actions are proposed in this strategy, including but not limited to:

- Strengthening inter-agency cooperation to improve care for victims.

- Fully integrating traffic victims in crime victims' assistance offices and strengthening the assistance provided to them.

- Updating the System for the Assessment of Damages caused to persons in traffic accidents, pursuant to the recommendations of the Monitoring Commission created under Law 35/2015.

- Strengthening the monitoring of the evolution of road traffic victims to analyse the impact of non-immediate damages and affect effects.

- Promoting and enhancing the visibility of psychological and legal care activities of non-profit organisations representing traffic victims[34].

It should be noted that the Road Safety Strategy, as we have already mentioned, is a road map that serves as a guide for the actions of the different institutions involved in road safety. Therefore, it cannot be indifferent to the Public Prosecutor's Office. In addition, many of the actions proposed to achieve the proposed objectives are related to the functions of the Public Prosecutor's Office in the field of road safety. As highlighted, this connection can be seen both from the perspective of the criminal prosecution of these conducts (updating the criminal framework and strengthening the fight against traffic offences) and from the perspective of protection, in a wider sense, of the victims (reducing response times and improving assistance in the event of an accident and guaranteeing the rights of traffic victims).

7. GENERAL MATTERS IN RELATION TO THE PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ROAD SAFETY

Mobility and road safety are affected by people's lifestyle habits[35].

The expected evolution of road safety in the coming years will depend not only on endogenous factors associated with road safety policies, but also on exogenous trends in the field of mobility and society in general. In this regard, in line with the 2030 Road Safety Strategy, worth particular note are[36]:

- Climate change. The 27 Member States of the European Union are committed to making the EU the world's first climate neutral zone by 2050. To achieve this, emissions are to be reduced by at least 55% below 1990 levels by 2030. The transport sector is the second largest polluter after the energy sector, producing more than 20% of GHG emissions across Europe. These environmental policies will bring about significant changes in mobility in the coming years, both in the modal distribution of transport and its volume and in people's mobility patterns, which will greatly affect mobility in urban environments.

- Population ageing. In 2030, 24% of our country's population will be aged 65 and over.

- Population growth in cities and population decline in rural areas. There are two challenges. On the one hand, safe travel in urban and peripheral urban areas with increasing mobility needs. In addition, the emergence of new forms of mobility that aim to respond to these needs, and the ageing of the population, already mentioned, are also contributing to this area. Furthermore, the safety of journeys in increasingly depopulated rural areas, which are mostly made on conventional roads. Moreover, in these areas the impact of population ageing is even greater.

- New forms of mobility: personal mobility vehicles[37], electric bicycles, conventional electric traction vehicles, shared vehicles, vehicles dedicated to urban goods distribution, etc.

- Technological progress. Both in infrastructures and traffic monitoring and management systems (connectivity and use of big data), as well as in vehicles (ADAS, connectivity, ITS, automatic driving, electric propulsion), the aim is to reduce the accident rate attributable to errors and risky behaviour, although it poses the challenge of properly integrating technology to prevent the emergence of new risks.

- The culture of young people. They are committed to usage, sharing, sustainability, multimodal mobility and smartphones. In other words, some of the trends outlined above are particularly important to this group, which is why it is expected that these trends will increase in importance in the future.

- Road safety at organisations (companies and administrations). Both social organisations (such as companies, associations, universities) and public administrations have an enormous influence on society through a wide variety of factors that can be used to improve road safety. Directly, by promoting road safety for their employees, customers and suppliers. Indirectly, by adopting road safety criteria in their value chain, in their purchasing decisions for goods and services needed to perform their functions and ensure the safety of their products. Furthermore, the percentage weight of road traffic accidents (RTAs) in minor accidents at work is 11.8%, which increases progressively as accidents become more serious: RTAs account for 21.8% of serious accidents at work and, in the case of fatal accidents at work, this percentage rises to 32.4%. In other words, occupational road traffic accidents have become one of the leading causes of death in terms of occupational accidents[38].

As we are talking about the future, I think it is vitally important that we mention training.

Road safety education is one of the fundamental pillars of road safety. Since the 2022-2023 school year, minimum road safety content has been taught at primary schools and secondary schools, following the approval of Royal Decree 157/2022 of 1 March, establishing the organisation and minimum teaching of Primary Education, and Royal Decree 217/2022 of 29 March, establishing the organisation and minimum teaching of Compulsory Secondary Education.

In light of the above, there is no doubt that road safety (and mobility in general) needs to be considered as an issue to be addressed from a multidisciplinary perspective.

8. THE IMPORTANCE OF ROAD SAFETY

In doctrine[39], road safety is considered as the series of conditions established by the legal system for the protection of life, health, physical integrity and other individual legal assets, in which driving a motor vehicle represents a legally permissible risk[40].

Road safety is a greater legal right, but linked to individual legal rights, playing a role in guaranteeing them[41].

As far as case law is concerned, Constitutional Court Ruling No. 161/1997 of 2 October 1997 states that “driving motor vehicles is an activity that can seriously endanger the life and physical integrity of many people, to the extent that it is now the leading cause of death in an age group of the Spanish population; hence, as with many other potentially dangerous activities, it is fully justifiable that the public authorities, who must first and foremost watch over the lives of citizens, make the exercise of this activity subject to compliance with strict requirements, subject those who wish to carry it out to preventive controls performed by the public authorities and impose sanctions for non-compliance consistent with the seriousness of the goods to be protected”.

In turn, Supreme Court Ruling No. 420/2023, of 31 May, also indicates that "driving a motor vehicle always generates a danger to the life and physical integrity of persons, and must therefore be carried out with great diligence". And also Supreme Court Ruling No. 105/2022, of 9 February, points out that “road safety, considered as an intermediate legal right that punishes the risks to the life and integrity of persons caused by driving motor vehicles, thus anticipating the protection of these personal assets”.

When referring to the crimes of homicide or reckless injury in the field of road safety, we are no longer talking about the legal right of road safety but directly about legal rights of the highest level, such as life or the health and physical integrity of persons.

When considering the statistical data and taking into account the importance of the legal rights at stake, it is clear that road safety is a major concern[42] and relevant for an institution such as the Public Prosecutor's Office.

In the face of the figures, society must not consign itself to a resigned sense of fatalism, as if the dramas behind the figures were a necessary part of road mobility[43]. In some areas, such as road traffic, a certain level of risk is accepted given its social utility but only up to a certain level that is considered socially bearable. Therefore, the legal system sets limits to this permitted risk, establishing standards of care which, if exceeded, make the allocation of the result viable, should it occur. Alongside the undoubted benefits it provides, there are certain negative effects (pollution, accidents, etc.) that need to be addressed, of which the latter is worth particular mention. On the other hand, despite the different elements involved in a road accident (vehicle, infrastructure, etc.) the human factor occupies a fundamental place[44].

Although not all deaths are the result of criminally reprehensible behaviour, the figures indicate that the human and social problem is of the utmost importance. Behaviours that entail disregard for the life or physical integrity of others or unforgivable carelessness constitute a significant portion of the determining causes of these tragic figures[45].