Fernando Galiana Marina

Lieutenant Colonel of the Guardia Civil

PhD Law

COOMPERATION: SUSTAINABLE MIGRATION MANAGEMENT MODEL BASED ON RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS

COOMPERATION: SUSTAINABLE MIGRATION MANAGEMENT MODEL BASED ON RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION 2. MIGRATION AND JURISDICTIONAL GUARANTEES. 2.1. State of play. 2.2. Where to go from here. 3. PERCEPTION, DISCOURSE AND SECURITISATION. 4. PENDULAR MIGRATION AND JUDICIAL HARMONISATION. 5. COOMPERATION AND EUROPEAN CITIZENSHIP. 6. CONCLUSIONS

Abstract: The quasi-omnipresence of the migration phenomenon in the media during the last decade has transformed the immigration discourse, generating changes in migratory perception, legislation and policy. Research on this matter promotes migration management from a paradigm of coomperation, understood as a sustainable model benefitting all actors involved, while contributing to the achievement of a common objective from an approach based on respect for human rights and their jurisdictional guarantees. From this model, the article proposes to consider the opportunity that migratory flows offer to revitalize the economy, promote entrepreneurship and contribute to the sustainability of the European welfare state.

Resumen: La cuasi omnipresencia del fenómeno migratorio en los medios de comunicación durante la última década ha transformado el discurso migratorio, generando cambios en la percepción, legislación y política migratoria. La investigación del fenómeno aconseja realizar la gestión migratoria desde un paradigma de coomperación, entendida como un modelo sostenible que beneficie a todos los actores implicados, mientras contribuye a la consecución de un objetivo común desde un enfoque basado en el respeto a los derechos humanos y sus garantías jurisdiccionales. Desde este modelo, el artículo propone considerar la oportunidad que ofrecen los flujos migratorios para revitalizar la economía, fomentar el emprendimiento y contribuir a la sostenibilidad del estado de bienestar europeo.

Keywords: immigration management, human rights, securitization, coomperation, European Union.

Palabras clave: gestión migratoria, derechos humanos, securitización, coomperación, Unión Europea.

ABBREVIATIONS

D-Jil Democracy Joint Intramural League

EBSOMED Enhancing Business Support Organisations

MED-Up! Promoting social entrepreneurship in the Mediterranean region.

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals.

UN United Nations

ENP European Neighbourhood Policy

ECHR European Court of Human Rights

Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)

EU European Union

1. INTRODUCTION

The continuous succession of migrant arrivals[1] to the Mediterranean coasts in 2015, the result of events that led to one of the largest human exoduses ever experienced, triggered numerous debates that seemed to forget that all human beings, as Saint Francis once said, are homines viatores, everlasting travellers since the first glimpses of humanity were seen in the primitive hominids that populated Africa.

In fact, all anthropological theses purport that humanity has flowed from one place to another, with two fundamental motivations (Petersen, 1958): to find new territories where they can continue to maintain a good standard of living (conservative migrations) or the search better ones that also satisfy the need for knowledge, discovery and research (innovative migrations). The author went so far as to state that settling in a territory is tantamount to resting until the next migratory need arises.

Thus, migration, the thirst for movement, mutability and the capacity for human plasticity are a constant. Heraclitus' panta rei[2] in Greek antiquity and Bauman's (2000) liquid society reiterate that siamo movile[3], transforming ourselves to adapt to the realities of the environment. In the face of this, thinkers from Erasmus of Rotterdam, the first European citizen, to Jean Claude Juncker urge the need for us to support hinge-migrants, who turn separation into cooperation.

As well as these ideas, it is worth mentioning Francisco de Vitoria, the father of human rights, who established the right of human communications (ius communicationis), defending the lawfulness of travelling to other territories in order to promote relations between peoples and cultures. His words are echoed in the search for a migration management formula in accordance with these rights, their guarantees and sustainability itself, declared in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, through which the UN has sought to call us to action[4]. This formula for sustainability and mutual benefit finds their key in the cooperative management of migration, organised to benefit all stakeholders.

2. MIGRATION AND JURISDICTIONAL GUARANTEES

2.1. STATE OF PLAY

Studies on migration set out to determine its causes, which were established in the 19th century in laws published by Ravenstein (1885, 1889), which listed the seven push and pull factors that, with certain nuances, still describe migration flows. In the early 20th century, Lee (1966) added that these migratory factors are not weighed rationally, but that the migration decision is influenced, to a high degree, by an irrational component that considers personal factors and others associated with points of origin, destination and transit.

Delving deeper into migration, Fawcett (1989) explained the importance of the links or pathways between those who migrate and the territory they wish to reach. He distinguished between tangible (mainly economic and labour), regulatory (regulations and obligations, including family) and relational (cultural similarities, status and supply-demand factors) links, adding that these are established through state cooperation, mass culture, personal ties and migration agencies.

Gradually, this type of studies focused on labour, social, and cultural issues (including the challenge of integration), as well as irregular migration, human trafficking and asylum (Triandafyllidou, 2019; Mainwaring, 2019). The 2015 migration crisis transformed securitisation parameters used[5] (Goularas et al., 2020) and proposed a humanitarian and solidarity perspective (Serfozo, 2017; Agarin and Nancheva, 2018), while at the same time reviewing the evolution of human rights towards a greater guarantee of terms (Donnelly and Whelan, 2018; Chetail, 2019; Costello, 2019; Baumgärtel, 2019; Sanz Mulas, 2019). They show that we are at the dawn of the definition of a new generation of emerging rights (solidarity, coexistence, peace, knowledge...), based on the cross-cutting principles that must characterise a 21st-century democracy. At the same time, this debate contributes to strengthening legislation and the enforcement of established rights.

Thus, the securitisationist trend that began in the 1970s has evolved towards increasingly securitising tendencies, both in legislation and jurisprudence, although there is still a strong discursive strand that anchors its concern in the need for securitisation of European territory and identity (Murray, 2018). On the other hand, Gatrell (2019) seeks to eradicate the hate speech about migration, recalling that migration has been a key element in the shaping of Europe. In the same vein, a new analysis is made of the colonial distribution of Africa, trying to find a policy that balances the migration based on solidarity, avoiding "nationalist selfishness", but without falling into "humanitarian naivety"[6].

Thus, Europe is encouraged not to forget the safety valve of its migratory past, urging it to assume its share of responsibility for current migration flows (Lehmann, 2015) and to curb both the organised crime responsible for the new slavery in the form of human trafficking (Castles et al., 2014; Gatrell, 2019), and the coercive use of migration (Greenhill, 2010). Current publications on migration point to the need to reconcile the two existing perspectives on the phenomenon: securitisation and the management of flows from a humanitarian perspective.

2.2. WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

The continent of Europe emerged and grew thanks to its migratory nature, a trend that continues to nourish the Mediterranean coasts, transforming the environment according to local and/or global events. Given this mutating reality, society cannot function with the worldview inherited from past generations, but, attempting to understand its environment, must cooperate to continue weaving the tapestry in which our interests are intertwined. Such a canvas allows for the exchange of ideas that promote social development, but it is also the platform through which crises and conflicts are expanded and magnified. Hence the need to "face our fears and adapt to new realities" (Adams and Carfagna, 2006), supporting and encouraging institutions so that, on the one hand, from the legislative and jurisdictional sphere, responsibility is assumed in the face of global problems and, on the other, from the educational system, the necessary skills are provided to combine the local with the global, understanding and adapting to the links that connect us.

The volatility,

uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity of our reality call for "Vasudhaiv

Kutumbakkam" (Nandram and Bindish, 2017), a concept that urges

collaborative innovation that integrates the diversity of the dynamic

environment through 'integrative intelligence', from an adaptive, reciprocal

and functional perspective. Thus, by applying the appropriate legal framework,

the EU must transform challenges into opportunities for enrichment and

development in order to avoid conflict situations that lead to a Hobbesian

state of destruction and loss of well-being (Galtung, 2004).

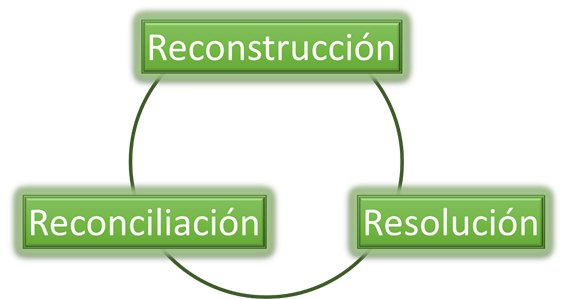

Graph 1

The ABC that perpetuates the cycle of violence[7].

Source: prepared by the author, based on Galtung (2004).

Given this possibility, the EU cannot allow the current conflict or migratory crisis to turn into an cold war in which the continent would renounce its humanity, as well as the cultural progress and civilisations that have characterised it. Therefore, reconciliation, reconstruction and resolution are needed to address hotspots and the migration challenge before they deteriorate into unrest and social fracture, making it difficult to embrace the mutual benefits they can offer.

Figure 2

The virtuous circle of the three Rs[8].

Source: prepared by the author, based on Galtung (2004).

Although the Brahimi report (UN, 2000) did not mention the migratory conflicts that would reach European shores a few years later, the implementation of its proposals serves both to improve the situation in the migrants’ countries of origin and to channel actions to keep the peace in Europe. It is therefore important to go beyond the surface of the problem, getting to the root of the issue and avoiding alienating any of the actors involved, as ignoring their well being may be one of the causes that prevents the conflict from healing and moving towards a situation of prosperity and overall well being. Nations must be able to take control of their peaceful destinies in order to steer the country and prevent populist policies like as anti-migration policies from causing relapse into conflict (Rubin, 2005).

The EU must therefore be able to seize the moment to demonstrate and reinforce its long-standing commitment to human rights and its responsibility as a beacon of welfare. Thus, its social commitment to human rights and justice in migration management can serve as a reference for resolving internal contradictions in the face of further flows of people (Velasco and La Barbera, 2020). To this end, the Union must adopt a common policy line to consolidate the prosperity of those who live within it, promoting the values that have enabled it to survive. It must also seize new opportunities to reinvent itself, embrace new concepts and welcome new blood to revitalise its innovative, industrial, commercial and cultural energy.

Effective management of the migration crisis can strengthens Europe's image as a global actor capable of resolving internal challenges, while helping to resolve global issues. The implementation of a common policy, both among EU members and among countries that are part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), would be more beneficial to all actors involved than if the piecemeal situation of individual measures adopted by each of the parties were to be perpetuated.

In shaping the new common policy on migration management, it has been necessary to recognise that the members of the ENP are more than a safety belt for European values. Hence the creation of several programmes which have been running since 2018, such as EBSOMED[9], designed to improve business support organisations and business networks in the southern neighbourhood; D-Jil[10], aimed at supporting young people from the Arab world to improve their autonomy and involvement in society through access to media; and MedUP![11], which aims to create an atmosphere that will enable the social entrepreneurship sector to flourish, which in turn will enable inclusive growth and job creation.

The countries involved in these projects can provide the nourishment that enables both European regeneration and the maintenance of its welfare state, provided that, in addition to the implementation of capacity-building, entrepreneurship and technical-financial support programmes, appropriate measures are taken so that migration flows can be channelled through legal channels that offer adequate alternatives that suit all parties involved in the process.

3. PERCEPTION, DISCOURSE AND SECURITISATION

It is now a decade since the tragic shipwreck off Lampedusa in October 2013. However, the news that constantly reaches us shows that the so-called migration crisis in the Mediterranean, which was then underway, is not a one-off event, but rather a phenomenon that is the backbone of Europe's very existence and that, however much it appears in the media, will continue as it has been doing for thousands of years (Galiana, 2024).

Therefore, as long as there are differences between the northern and southern hemispheres, as long as we continue to feel the effects of climate change or health crises, and whilst democratic freedom is not present in all parts of the world, migratory pressures will continue, and they will not be resolved with border protection. No matter how many obstacles are put in place, just as water eventually breaks through the thickest of stones, migration flows will also eventually find a way through a fortress. The problem arises when, in the absence of adequate channels, they find themselves in the most dangerous place, and the one that brings the least benefit to them and to the society they reach.

The magnification of the migration phenomenon that occurred in a Europe has been mired in successive crises for years. But these are first-world crises, crises in countries where a level of well-being has been achieved that other people can only dream of. Europe has become the new El Dorado for hundreds of thousands of migrants yearning for a decent standard of living. And Europe cannot ignore this reality while it is based on the pillars of human dignity. Moreover, it needs new migration flows to maintain the welfare of those who are already part of it.

However, in order to integrate migration flows and build a sustainable society in which all parties benefit, we must start with something simple - the word - because, as was said thousands of years ago, in the beginning was the word, and since the word is the beginning of action and thought, the discourse on migration cannot degenerate into alarmist tropes. The importance of the word is seen in the effects of media sensationalism that portrayed migration in terms of disaster, chaos and violence in 2015(Mukhortikova, 2018), provoking a reaction of alarm among Europeans, who felt that the EU would not be able to absorb the migrants arriving on its shores.

An example of words influencing thought and actions was seen in how the aforementioned sensationalist discourse disseminated an anti-immigration climate that eroded perceptions of migration. In the midst of the economic instability affected in Europe, the way the phenomenon of migration was presented took on negative overtones and came to be perceived as the most pressing concern for European society, as can be seen in the series of Eurobarometers published between the spring of 2015 and the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Migration was thus presented as an irregular competitor. And in the midst of a crisis, it seemed almost impossible to integrate the people who were seen as a human wave appropriating limited resources.

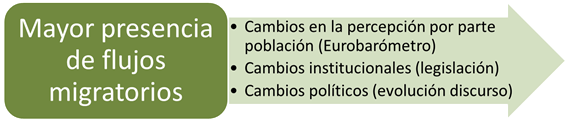

Figure 3

Changes resulting from the presence of migration flows[12].

Source:

created by the author.

Source:

created by the author.

At this juncture it is worth recalling the research of political scientist Ole Wæver (1989) who concludes that the very enunciation of the concept of security with that of migration is an act of securitisation that transforms the perception of the reality of migration. Confirming this assertion, during the last decade, the discourse of alarm has encouraged certain political agendas. Social discontent has been harnessed and channelled into questioning the EU's basic pillars and rejecting multicultural elements. This rhetoric of alarm and fear has sown radicalisation, dissent and social polarisation, while concealing the potential positive impact of migration flows in an eagerness to link them to any kind of social problem.

At the same time, as a consequence of the fear generated by alarmist discourses, a narrative of insecurity has been forming that has gradually laid the foundations for the building of a wall that seems to increasingly divide the two hemispheres. As a result of this rhetoric, in the midst of this maelstrom, migration ceased to be perceived as a purely beneficial reality for the receiving countries and began to be defined in terms of risk and threat to the survival of the liberal world's established way of life. As a result, the political agenda of securitisation and border shielding gained ground, hindering the ability to reach cooperative migration pacts (Ibahim 2005).

The data show a parallel between, on the one hand, greater social alarm and anti-immigration discourses and, on the other hand, a higher volume of hate crimes related to racism, xenophobia, and religious beliefs or practices (particularly against those professing Islam). In fact, the volume of hate crimes multiplied exponentially from 2014 until the outbreak of the pandemic[13], which could be linked to the popularisation of hate rhetoric and dehumanisation fostered among some political groups (Amnesty International, 2017).

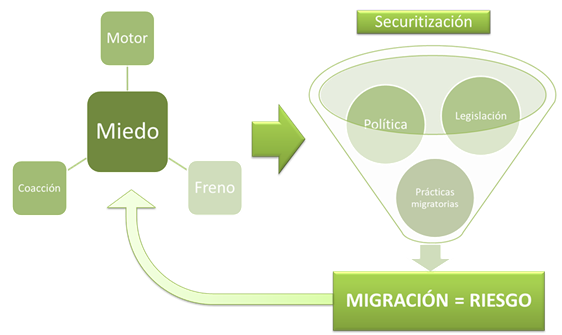

Figure 4

Correlation between fear and securitisation measures.[14]

Source: created by the author.

Source: created by the author.

This situation only creates an endless circle. On the one hand, are the spread of alarm and the anti-immigration climate as drivers of hatred that encourage this type of crime. On the other, there is a demand for securitisation measures in the face of migration that is being perceived as a problem, because this is how the alarmist discourses present it. Thus, the illocutionary force of the word has become perlocutionary and has transferred the migration problem to political forums, creating the migration and securitisation binomial.

The circle has already been completed because the adoption of securitisation measures on migration only multiplies the headlines featuring the phenomenon. And the wheel starts again, causing the perception of migration as a cause for instability and insecurity to persist and grow. This leads to more alarm, more hatred, more violence, which leads to more demand for securitisation. This vicious feedback loop between alarm and securitisation must be ruptured. It is urgent because, as seen on a daily basis, migration is part of the European reality.

4. PENDULAR MIGRATION AND JUDICIAL HARMONISATION

Spain and the Guardia Civil specifically, have been aware of this phenomenon for decades. The 2006 the Cayucos crisis was a watershed in terms of migration (Galiana, 2024). It took Europe almost ten years to realise what was already visible on Spanish shores, but then seemed to be something that of concern to Spain alone.

The year 2006 saw the migratory pendulum swing to Europe's westernmost route. Over time, flows shifted from west to east, to make the reverse movement. And, once again, from what we are seeing, it is starting to repeat the west to east movement. This pendulum swing entices us to reflect on the reasons for these preferences. We saw that migrants do not necessarily choose the route that is closest to them.

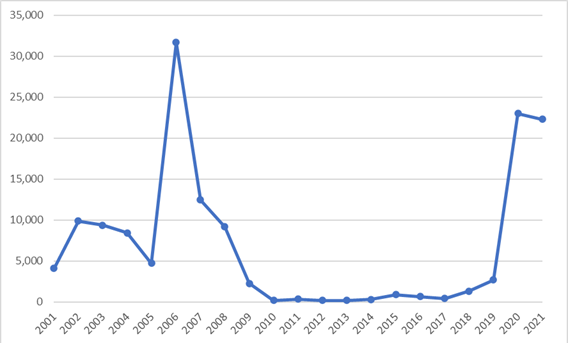

Figure 5

Evolution of vessel arrivals in the Canary Islands (2001- 2021).

Source: Ministry of the Interior (2021), prepared by the author.

The work carried out on the western route since 2006, thanks to the experience gained by the Coordinating Authority, forced migration mafias to find alternative routes. In the following decade, the concentration of assets in the East led to the activation of Western routes that seemed to have been forgotten in the face of the emergency declared on the Aegean coasts and in Italian waters.

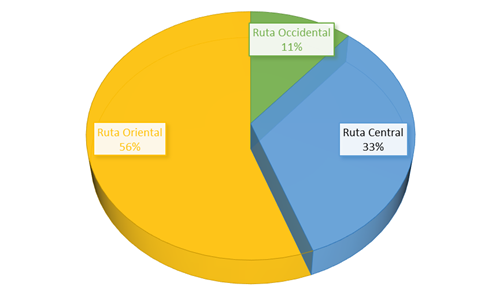

Table 1

Percentage distribution of annual arrivals via Mediterranean routes (2014-2021).

|

Year |

Western |

Central |

Eastern |

|

2014 |

5% |

76% |

19% |

|

2015 |

2% |

15% |

83% |

|

2016 |

4% |

49% |

48% |

|

2017 |

15% |

64% |

20% |

|

2018 |

47% |

17% |

37% |

|

2019 |

27% |

11% |

62% |

|

2020 |

46% |

37% |

17% |

|

2021 |

34% |

54% |

12% |

|

Total |

11% |

33% |

56% |

Source: UNHCR (2021), prepared by UNHCR.

Figure 6

Percentage of total arrivals via Mediterranean routes between 2014 and 2021[15]

Source: UNHCR (2021), prepared by UNHCR.

The reactivation of the routes enables us to learn a very clear lesson from the present migratory situation: the routes remain dormant until circumstances bring about their reactivation. Because of this, the EU needs to ensure coordinated management, guaranteeing the continuity of operations that curb the activities of migratory mafias. These mafias find the most vulnerable points, multiplying the danger of the movements and increasing the risk to migrants' lives.

On the subject of migration mafias, it is necessary to talk about human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, which often uses these routes. For example, it is worth citing the Supreme Court Ruling of 22 April 2022, which details how a Nigerian minor was brought to Spain under the promise of finding her a job unrelated to prostitution. However, when she arrived, she was kept a prostitution ring from which she could not escape until she was rescued by the State Security Forces.

In light of the strategies used by migratory mafias, it is important to note the correctness and rectitude of the actions of the Guardia Civil in its management of migration flows, which has been highlighted in several European and national rulings. Examples include the opinion expressed by Judge Dedov in the judgement of 3 October 2017 of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), as well as in the judgement of 13 February 2020 of that same court. This is the ruling on the assaults on the Melilla border fences on 13 August 2014, one of the most numerous until that date, characterised, moreover, by the use of force by the migrants. The judgement highlights how the migrants did not make use of the legal procedures in place for them to enter Spanish territory legally, as indicated by the provisions on the crossing of external borders of the Schengen area.

This ECtHR judgement is cited for its importance to the Spanish legal system and for the actions of the police forces in charge of border surveillance. The Court noted the excellent work done by Spain in safeguarding human rights, while taking the necessary actions to protect the borders. This was recognition and support for the efforts made to bring migration into regular channels, always with respect for human rights and jurisdictional guarantees. Also in Spain, the ruling of 28 January 2021 of the Constitutional Court, for example, emphasises the legitimacy and proportionality of the actions of the Spanish Armed Forces in matters related to migration flows.

More recently, during October 2023, the ECtHR ruled on several cases related to mass arrivals of irregular migrants in Hungary (Sahzad v Hungary; in the matter of S.S. and others v Hungary) and Malta (A.D. v Malta). In these cases, the court found violations of Articles 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment) and 4 of Protocol No. 4 (prohibition of collective expulsion) of the European Convention on Human Rights. Such situations have led to the publication of the Administrative detention of migrants and asylum seekers guide for practitioners (Council of Europe, 2023), as well as an Action Plan to Protect Vulnerable Persons in the Context of Migration and Asylum in Europe (2021-2025). Although it deals with other realities, at this point it is also important to note the strategy to promote children's rights (2022-2027), as the possibility of developing many of their rights directly impacts on the situation derived from their migratory status or that of their families.

These guidelines, together with the EU's migration policy, which has recently been supplemented by the new pact on migration and asylum (20 December 2023), signed during the Office of the Presidency[16], promote a more cooperative and sustainable management of migration flows. In this regard, among the other modifications introduced by the new text is the proviso that, in certain circumstances, asylum applications should not be processed in the country of entry or legal stay. In addition, it extends the criteria for family reunification to integrate members who are eligible for international protection, as well as those who have obtained citizenship by obtaining a long-term residence permit and newborns.

It should be noted that the current migration situation has led to an exponential increase in the number of cases brought before European courts. Such a situation invites an attempt to avoid the collapse of the European courts by creating a system of domestic European courts through which to extend the capacity for action of the two European courts. Based on their coordination, domestic courts would reinforce the consistency of judgements and compile precedents with which to promote the advancement of jurisprudence.

Through this coordination, legal harmonisation aims to avoid disparate outcomes depending on the court to which the appeal is made. For example, in order to determine the right to remain in the EU, cases brought before the ECtHR invoking Article 8 of the European Charter of Human Rights must demonstrate the difficulty of continuing family life if all or part of the family unit moves outside the EU. In contrast, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) avoids the interpretative subjectivity of family reunification and analyses such cases from the point of view of European citizenship and freedom of movement. As a result, the sentencing of one and the other often differs.

Therefore, cases heard by the ECtHR, such as Omoregie, have to organise their defence around the difficulty that the person leaving would have in continuing family life if forced to leave the country where he or she is. On the other hand, cases heard by the CJEU focus their defence on issues related to European citizenship and the rights deriving from it, such as the right to lead a normal family life. Since these cases are based on the right of any citizen to lead a normal family life, the request for any family member (e.g. the father in the Metock or Zambrano case) to settle in a third country is misplaced. This impediment arises because their departure would not allow the remainder of the family, who do have EU citizenship, to lead a normal family life. So, in this court, the rights of European citizens take precedence over all other premises.

It is these differences in the types of argument used in the cases before the two courts that have led to the assertion that they need to coordinate strategic adjudication. Therefore, their rulings, as pointed out by Costello (2019(, will serve as a catalyst for the entire EU and its member states to achieve standardised governance of the migration phenomenon based on the advancement of human rights and their jurisdictional guarantees.

It is therefore necessary that the European Court of Human Rights and the European Court of Justice take a harmonious and cohesive approach to the resolution of such cases. Based on the European values of solidarity, harmony, humanitarian protection and inclusion, these courts must lay the foundations of the Union's legal order. This judicial harmonisation must go hand in hand with the design of legislation and migration policy that channels migration in a regulated way, preventing migrants from seeing the illegal routes offered by migration mafias as the only way to access the continent.

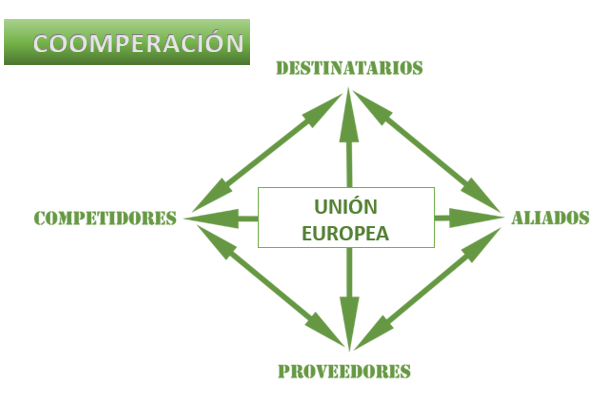

5. COOMPERATION AND EUROPEAN CITIZENSHIP

The aforementioned cooperation between European courts is just one of the actors where joint and coordinated efforts are needed to achieve effective, sustainable management of migration flows. At this point, the concept of coomperation is introduced, conceived as a framework of necessary cooperation among all the stakeholder involved in migration management, in which each stakeholder's own interests must also be taken into account. It is based on the coomperation model that Brandenburger and Naleduff (1996) apply in the world of economics and business management, combining co-operation and competitiveness. Renaming it here as coomperation further emphasises the cooperative element of the model. In coomperation, negotiating parties must demonstrate their ability to adapt in order to build alliances that allow them to move forward simultaneously on several tracks.

On the one hand, they must move forward motivated by mutual benefit. Achieving this will make the actions sustainable. At the same time, these alliances must allow them to pursue their own interests, which must never run counter to, nor hinder, the common good. Thus, in the coomperation model (Galiana, 2024), the EU lies in the centre, as it is at the heart of the interaction with the other stakeholders in the model. The following are also round them and must collaborate:

1. The countries of origin and transit of migration, which are the suppliers. At the same time, it is essential to establish links with the destinations in order to improve their situation.

2. Competitors, which are stakeholders whose actions reduce the potential benefits that the EU can derive from migration flows. Migration mafias are prominent in this group of competitors. It also includes fragile states that hinder the implementation of legal migration mechanisms. Also in this group are EU member states that do not want to cooperate with the common migration policy.

3. Allies, which include countries that follow the common migration policy, as well as international organisations (both public and private) whose agendas are similar to that of the EU.

4. Target groups, subdivided into two: on the one hand, the migrants themselves, who want to improve their situation and, on the other hand, the population in the state to which the migrant arrives and who want the EU welfare state to be maintained.

The key to the successful use of coomperation in migration management lies in the search for a meeting point that allows the specific objectives of each party to be combined with the common good: the objectives of each individual State, of the EU, of the migrants, of collaborating companies and institutions, of the countries of origin and transit... This meeting point is none other than the Pareto optimal point of game theory. To find it, the potential for entrepreneurship and creation offered by migration flows must be harnessed.

Figure 7

Diagram of the Coomperation concept as applied to the European Union[17].

Source: the author, based on

Branderburger and Nalebuff (1996).

Source: the author, based on

Branderburger and Nalebuff (1996).

Furthermore, in migration negotiations and management, according to the postulates of Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Prize-winning economist (Ostrom, 1990; Ostrom et al., 1999; Ostrom and Ostrom, 2003; Hess and Ostrom, 2007), the EU must consider the four levels involved in the migration process.

• At the bottom are the actions carried out by the member state (the micro level).

• This is followed by those carried out by the EU as a whole.

• The next level is occupied by those of third states and international institutions.

• And finally, the top level consists of those that involve the entire migration network (the macro level).

This will lead to multi-level governance, a necessary step in an increasingly liquid world where economic realities merge with climate situations and social instability. In this sense, the pandemic has demonstrated the importance and necessity of involving all stakeholders in the phenomenon. It has made it clear that, in addition to the resources and support of the public and private sectors, we need to include the public at large, both those who are already in Europe and those who want to come.

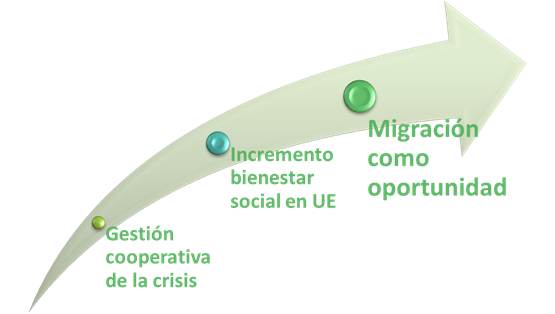

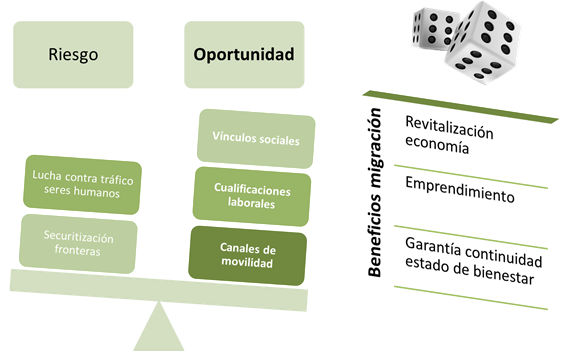

The new migration regime must therefore set aside the notion of migration as a risk and embrace the regenerative and revitalising opportunity it brings, making migrants active stakeholders contributing to sustainability. With the 2030 Agenda as the main framework, coordinated, multidisciplinary and multilevel action must be taken to promote European well-being. At the same time, these actions must promote the development of the countries of origin and transit of migration flows, strengthening cooperative links.

Figure 8

Cooperative migration management enhances social welfare and makes migration an opportunity.

Source: Created by the author.

Source: Created by the author.

In short, we must keep learning to continue building the society of which we are a part. The survival of European welfare depends on its ability to adapt to the surrounding reality, accepting the wealth that arrives on its territory, educating it in its values and learning new ones. Therefore, we cannot permit a type of acculturation that traumatises, ignores and fails to exploit the potential of those arriving in Europe. In order to succeed, the construction of this new stage of Europe must be based on respect and understanding, through fertile hybridisations that achieve sustainable entrepreneurship and cultural regeneration through personalised intake and learning programmes that consolidate European well-being, embracing the strength brought by migration flows. To this end, the benefits of the information and communication technologies, which have proved so useful since the outbreak of the pandemic, should be harnessed. They must therefore be used to integrate migrants into the host society and for integration in employment.

Figure 9

Migration as an opportunity[18].

Source: created by the author.

Source: created by the author.

These programmes must receive support from the public sector, the private sector and citizens. This coomperative action can make the promotion of sustainable entrepreneurship and territorial connectivity a reality, thus offering a response to the depopulation of rural areas and the demographic decline taking place in Europe. These initiatives can be used to promote projects that encourage sustainable agricultural, livestock and energy practices. This is where the learning initiatives that can be delivered by combining face-to-face learning in rural areas with technology brought in from urban areas come into play. These initiatives offer a platform to revitalise traditions, as well as to enhance the value of the knowledge contributed by newcomers, combining them in a new reality adapted to the needs of our time.

However, for these initiatives to succeed and for the objectives of the 2030 Agenda and the sustainable management of migration flows to become a reality, civic values, rules of coexistence and the institutions that have made Europe an area of freedom, security and justice must be accepted.

To this end, civics and the concept of European citizenship must be promoted in inter-religious spaces that provide an understanding of how the existence of different faiths in the same community brings nuances that can enrich and strengthen society, as long as they are based on the values of respect for others and human rights, as well as the democratic principles of equality and tolerance. This respect must be mutual (from the local population towards the migrant population and from the migrant population towards the local population). Moreover, to get this respect, you have to be able to give it, because respect is not gained by imposing it.

Likewise, it is not possible to impose any idea, since these ideas are only propagated by promoting their assimilation through facts and arguments that demonstrate their coherence. Hence, this article proposes that any migration management programme developed by the EU must begin with coherence between discourse and action in order to establish the climate of respect necessary for coexistence to bear fruit in the development of a sustainable society, based on the values of respect and freedom that created Europe.

In short, the popular saying that warns of the need to adapt or die is no more than the dichotomy that is now once again facing the European Union in the form of the migration challenge. The new climatic, demographic, economic, political, social and technological realities have changed the context since the rules governing different European nations were drafted.

Therefore, from the introspective analysis of the Union's new reality, the idea of a strengthened Europe capable of managing the global challenges within and beyond its borders must re-emerge. Based on coordinated action from the Sustainable Development Agenda, and on a consolidated democracy that promotes multilevel governance, and flying the flag of a community built on respect for human rights and jurisdictional guarantees, Europe has the opportunity to transform the migration challenge into an opportunity for prosperity and well-being that is sustainable, effective and beneficial for all parties.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Firstly, sustainable migration management through the implementation of legal migratory channels cannot ignore the pendular movements (Galiana, 2024)[19] of the migratory routes exploited by various mafias, which makes it inadvisable for such routes to be declared closed at times when they are less travelled, as they remain latent and will reactivate as soon as it is realised that they have fewer security measures.

On the other hand, the chain between alarmist narratives, perceptions of insecurity and hate speech must be broken, as they foster racism and xenophobia, giving rise to new situations of alarm, which, in turn, add to the sense of insecurity and, once again, encourage more harmful discourse, transforming the situation into a spiral of growing unrest.

Hence the importance of promoting balanced discourses that allow people to see the potential of migration flows as an opportunity to revitalise the European continent, enabling it to adapt to new global challenges. It is important for the management of migration flows in Europe does not get lost in arguments centred on the level of diversity to achieve, and to be aware that, whatever its degree, Europe will exist if it is organised with respect for human rights and jurisdictional guarantees, as well as for the institutions and codes that underpin it.

Therefore, a change of narrative is needed to echo the inevitability of the migration phenomenon, to go beyond the traditional definitions of economic migrants versus refugees, and to push for the harmonisation of European Court rulings to help build a more coordinated migration management. It must also be based on principles of partnership, multilevel governance and the 2030 Agenda.

Thus, a multidisciplinary and multilevel approach, with all the dimensions and stakeholders involved, can promote European citizenship based on the principles of democratic respect. This European community will be responsible for promoting sustainable projects that include the migrant population so that, among everyone, the EU's welfare state can be maintained. With a narrative that harnesses all resources, migration can become a sustainable, effective and beneficial challenge for all parties involved in the process.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

UNHCR (2021). "Mediterranean situation. Operational Data Portal. Refugee situations, http://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean.

Adams, J. M., and Carfagna, A. (2006). Coming of age in a globalized world: the next generation. Kumarian Press, Bloomfield.

Agarin, T. and Nancheva, N. (2018). A European Crisis. Perspectives on Refugees, Solidarity and Europe, Verlag, Stuttgart.

Amnesty International (2017). Report 2016/17. The State of the World's Human Rights, London.

Bauman, Z. (2000). Modernidad líquida, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico, Argentina, Spain; translation: Liquid modernity, Economic Culture Fond, Mexico, Argentina, Spain. Mirta Rosenberg and Jaime Arrambide Squirru.

Baumgärtel, M. (2019). Demanding rights. Europe's supranational courts and the dilemma of migrant vulnerability, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York and Melbourne.

Brandenburger, Adam M. and Nalebuff, Barry J. (1996). Co-opetition, Currency Doubleday, New York.

Castles, S.; de Haas, H.; and Miller, M. J. (2014). The Age of Migration. Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK and New York, 5th Ed.

Chetail, V. (2019). International migration law. Oxford University Press, Oxford;

Council of Europe (2021). Action plan on Protecting Vulnerable Persons in the Context of Migration and Asylum in Europe, August, https://rm.coe.int/action-plan-on-protecting-vulnerable-persons-in-the-context-of-migrati/1680a409fc.

Council of Europe (2022). Strategy for the rights of the child (2022-2027). Children’s Rights in Action: from continuous implementation to joint innovation, March, https://rm.coe.int/council-of-europe-strategy-for-the-rights-of-the-child-2022-2027-child/1680a5ef27.

Council of Europe (2023). Administrative Detention of Migrants and Asylum Seekers. Guide for practitioners, November, https://rm.coe.int/administrative-detention-of-migrants-and-asylum-seekers-guide-for-prac/1680ad4c43

Council of the European Union (2023). The Council and the European Parliament reach breakthrough in reform of the EU asylum and migration system, Press release, 21 December, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/12/20/the-council-and-the-european-parliament-reach-breakthrough-in-reform-of-eu-asylum-and-migration-system/.

Costello, C. (2019). The Human Rights of Migrants and Refugees in European Law, Oxford Studies in European Law.

Donnelly, J. (2013). Universal Human Rights in Theory and in Practice. Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London, 3rd edition.

Donnelly, J. and Whelan, D. J. (2018). International Human Rights, Routledge, Dilemmas in World Politics, 5th edition, New York and Addington (Oxon, UK).

Fawcett, J. T. (1989). "Networks, Linkages, and Migration Systems", International Migration Review, 23, No. 3, Special Silver Anniversary Issue: International Migration an Assessment of the 90s, Autumn, pp.671-680.

Galiana Marina, F. (2024). El reto migratorio: una gobernanza global basada en el respeto a los derechos humanos y sus garantías jurisdiccionales como respuesta sostenible (The migration challenge: global governance based on respect for human rights and their jurisdictional guarantees as a sustainable response.) Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia.

Galtung, J. (2004). "Violence, war and its impact. On the visible and invisible effects of violence", Polylog,https://them.polylog.org/5/fgj-es.htm.

Gatrell, P. (2019). The Unsettling of Europe. How migration reshaped a continent. Hachette, New York.

Goularas, G.B.; Turkan Ipek, İşil Zeynep; and Önel, Edanur (2020). Refugee crisis and migration policies. From Local to Global, Lexington Books, Lanham, Boulder, New York and London.

Greenhill, K. M. (2010). Weapons of Mass Migration: Forced Displacement, Coercion, and Foreign Policy, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs, Cornell University Press.

Hess, C.; and Ostrom, E. (2007). Understanding Knowledge as a Commons. From theory to practice, MIT press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London (UK).

Ibahim, M. (2005). "The securitisation of migration: a racial discourse", International Migration, Vol. 43, No 5, pp.163-187.

Lee, E. S. (1966). "A theory of migration", Demography, Vol. 3, No. 1.

Lehmann, J.P. (2015). "Refugees and migrants: Europe's past history and future challenge', Forbes, 2 September, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jplehmann/2015/09/02/refugees-migrants-europes-past-history-and-future-challenge/#5c8e6921a7d4.

Mainwaring, Ć. (2019). At Europe's Edge: migration and crisis in the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press.

Ministry of the Interior (2021). Balances and reports, Government of Spain, http://www.interior.gob.es/prensa/balances-e-informes/.

Mukhortikova, Tatiana (2018). "Metaphorical representation of the European migration crisis in the Spanish and Russian press in 2017", Comunicación y medios, No. 38, pp. 12-26.

Murray, D. (2018) The strange death of Europe. Immigration, identity, Islam. Bloomsbury Continuum. London.

Nandram, S. S. and Bindish, P. K. (2017). Managing VUCA Through Integrative Self-Management. How to cope with Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity in Organizational Behaviour, Springer.

UN (2000), Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, A/55/305S/2000/809, 21 August, https://undocs.org/es/A/55/305.

Ostrom, E. (1990). “Governing the commons. The evolution of institutions for collective action”, Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E.; Burger, J.; Field, C. B.; Norgaard, R. B; and Policansky, D. (1999). "Revisiting the Commons: Local Lessons, Global Challenges”, Science, Vol. 284, No. 5412, pp. 278-282, 9 April.

Ostrom, V. y Ostrom, E. (2003). Rethinking Institutional Analysis: interviews with Vincent and Elinor Ostrom, with introductions by Vernon Smith & Gordon Tullock. Commemorating a lifetime of achievement, Mercatus Center, George Mason University.

Pakerham, T. (1991). The Scramble for Africa. London, Pub. Abacus, Hachette.

Petersen, W. (1958). “A general typology of migration”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 23, Nº3, June, pp.256-266.

Ravenstein, E. G. (1885). “The Laws of migration”, Journal of Statistical Society, 48, pp. 167-227.

Ravenstein, E. G. (1889). “The Laws of Migration”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 52, No. 2, June, pp.241-305.

Rubin, B. R. (2005). Consolidación de la paz, consolidación del estado: construir soberanía para la seguridad (Consolidation of peace, consolidation of the state: building sovereignty for security). Centro de Investigación para la paz (Centre for Peace Research), FUHEM, https://www.fuhem.es/media/cdv/file/biblioteca/Informes/Azules/RUBIN,%20Barnett,%20Consoilidaci%C3%B3n%20Paz.pdf.

Sanz Mulas, N. (2019). Los derechos humanos 70 años después de la Declaración Universal, Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia.

Serfozo, B., Pub. (2017). Escaping the Escape. Toward Solutions for the Humanitarian Migration Crisis, Berlin, ibidem-Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Smith, S. W. (2019). La huida hacia Europa. La joven África en marcha hacia el viejo continente, arpa. Translation by Javier García Soberón of La rue vers l'Europe (2018).

ECtHR, Judgement of 12 October 2023, Cases 56417/19 and 44245/20, S.S. and others https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-228029%22]}.

ECtHR, Judgement of 13 February 2020, Cases 8675/15 and 8697/15, N.D. and N.T. v. Spain, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/spa#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-201353%22]}.

ECtHR, Judgement of 17 October 2023, Case 12427/22, A.D. v. Malta https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-228153%22]}.

ECtHR, Judgement of 3 October 2017, 3rd Section (Applications No. 8675/15 and 8697/15), https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/spa#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-177683%22]}.

ECHR, Judgement of 31 July 2008, Case 265/07. https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22appno%22:[%22265/07%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-88012%22]}.

ECtHR, Judgement of 5 October 2023, Case 37967/18, Sahzad v. Hungary https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-227740%22]}.

CJEU, Judgement of 25 July 2008 in Case C-127/08, https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=68145&pageIndex=0&doclang=es&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=2802256.

CJEU, Judgement of 8 March 2011 in Case C-34/09 (Grand Chamber), https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=80236&pageIndex=0&doclang=es&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=2798035.

Triandafyllidou, A., Pub. (2019). Routledge Handbook of Immigration and Refugee Studies, London and New York,Routledge.

Constitutional Court, Plenary. Judgement 13/2021 of 28 January 2021. 3848/2015. (Spain). Individual votes. https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/docs/BOE/BOE-A-2021-2832.pdf.

Supreme Court, Judgement of 22 April 2022, 1739/2022 (Spain), https://www.poderjudicial.es/search/documento/TS/9957756/consecuencias%20de%20la%20infraccion%20penal/20220516.

Velasco, J.C. and La Barbera, M.C. (2020). "Migration and Borders in the Key of Justice", The Conversation 1 December, https://theconversation.com/migraciones-y-fronteras-en-clave-de-justicia-151013.

Wæver, O. (1989). Security, the Speech Act. Analysing the politics of a word, Working paper,https://www.academia.edu/2237994/Security_the_Speech_Act_working_paper_1989.