Anselmo del Moral Torres

Colonel of the Guardia Civil

Doctor of Law

MAIN TRENDS AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS AGAINST DRUG-RELATED ORGANISED CRIME IN THE 21ST CENTURY

MAIN TRENDS AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS AGAINST DRUG-RELATED ORGANISED CRIME IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE CONCEPT OF ORGANISED CRIME AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO TERRORISM. 3. SITUATION AND TREND ANALYSIS. 3.1. The US-Mexico Border. 3.2. Central America. 3.3. The case of Haiti. 3.4. Colombia. 3.5. Venezuela. 3.6. Ecuador. 3.7. Peru. 3.8. Brazil and the Triple Frontier. 3.9. Territories used for money laundering. Panama, Uruguay and the former British colonies. 3.10. The situation in Africa. 3.11. Trends in Europe. 4. STUDY OF POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS. CONCLUSIONS 4.1. Drug legalisation and its potential impact. 4.2. Eradication of plantations with natural herbicides and effective support for crop shifting. 4.3. Efficient, sustained and corruption-resistant public investment in deprived areas. 4.4. Arms control. 4.5. Prison dispersal policy. Prison control. 4.6. Effective regulation of tax havens. 4.7. Effective multilateralism in Africa. 4.8. Improving policies and strategies against organised drug trafficking-related crime in Europe. 4.8.1. Public investment policies in areas affected by drug trafficking. 4.8.2. Greater control at ports. 4.8.3. Improving investigative and judicial capacities against organised crime. 4.8.4. Joint and sustained operations against organised crime. 4.8.5. Efficient interoperability of information systems. 5. FINAL ASSESSMENT. 6. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Resumen: En el primer cuarto del siglo XXI asistimos al incremento y peligrosidad de la amenaza relacionada con el crimen organizado, principalmente relacionada con el tráfico de estupefacientes a nivel mundial, que ha llegado a confrontar a determinados Estados a niveles anteriormente desconocidos. Este artículo de investigación pretende analizar las causas de esta tendencia, pero, sobre todo, partiendo de la base del análisis de fuentes abiertas, y de la experiencia del autor que ha profundizado en la materia propuesta desde el punto de vista académico y profesional en los últimos cinco años, investigar sobre posibles hipótesis o soluciones que, con una visión estratégica y resiliente, a medio o largo plazo, pueden contribuir a controlar o reducir este tipo de amenazas.

Abstract: In the first quarter of the 21st century we are witnessing the increase and danger of the threat related to organized crime, mainly related to drug trafficking worldwide, which has come to confront certain States at previously unknown levels. This research article aims to analyze the causes of this trend, but, above all, based on the analysis of open sources, and the experience of the author who has delved into the proposed subject from an academic and professional point of view in the last five years, research possible hypotheses or solutions that, with a strategic and resilient vision, in the medium or long term, can contribute to controlling or reducing this type of threats.

Palabras clave: Siglo XXI, incIncrease in organised crime, drug trafficking, strategic and resistant solutions.

Keywords: 21st century, increase in organized crime, drug trafficking, strategic and resilient solutions.

ABBREVIATIONS

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1. INTRODUCTION

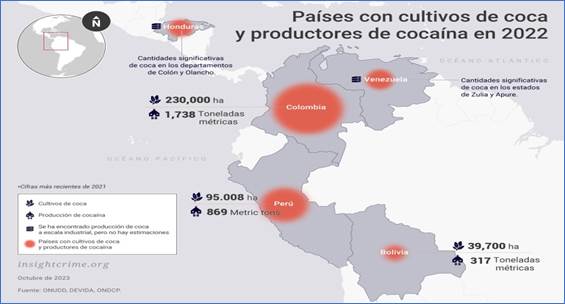

In recent years, there have been numerous reports of drug seizures in police operations, increasingly involving media of all kinds. But if we analyse other factors, such as the hectares of base crop plantations and facilities used to produce drugs, or the modus operandi employed by organised crime groups, including increased confrontation with law enforcement agencies, among other aspects, we can easily conclude that the impact of drug trafficking-related organised crime has increased in the first four years of the 21st century, despite the above-mentioned efforts. Indeed, we are witnessing an increase in the number of hectares devoted to coca leaf cultivation in the main coca producing countries: Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, as can be seen in figure 1, with an estimated record cocaine production of close to 3,000 tonnes in 2022, much higher than a decade earlier (Pasquali, 2023). This undoubtedly has an impact on public security in many countries, such as Spain, where the overproduction of cheaper cocaine at source multiplies consumption and drug-related crime at destination (Hidalgo, 2024).

Figure 1.

Countries with coca fields and farms in 2022 (INSIGHT)

We are also witnessing an increasingly dangerous type of organised crime that is confronting state institutions. Thus, while we have seen the fall of major Mexican cartel leaders, such as Chapo Guzmán, who served as leader of the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico until his arrest and extradition to the US in 2017, we have also seen organised crime engage in serious confrontations with the Mexican government in the form of militias with military equipment. This was the case of the incident provoked by the group led by his son, Ovidio Guzmán López, in the so-called Battle of Culiacán or culiacanazo in 2019 (UnoTV, 2020), or the wave of violence following his arrest by Mexican security forces in 2023. (González Díaz, 2023)

We are also witnessing organised crime become empowered in some countries, heavily infiltrating institutions, as in the case of the prison system in Ecuador. Only a few years ago, the country was considered one of the most peaceful in the region, but it has recently experienced the worst security crisis in its history (Mella, 2023). Only a few years ago, the country was considered one of the most peaceful in the region, but it has recently experienced the worst security crisis in its history, due to the increasing power of organised crime groups, mainly related to drug trafficking, such as: the Choneros, the Lagartos, the Lobos and the Tiguerones, among others (Observatorio Nacional del Narcotráfico de Ecuador, 2022). All are related to the control of prisons, and the struggles between them for control of drug trafficking, especially, but not exclusively, in the Guayaquil area. The lack of security led the President of the Republic to declare an "internal armed conflict" in January 2024 with a toughening of the fight against criminal groups involved in drug trafficking in the country (BBC, 2024).

But in Europe, mafias also operate in Spain, trafficking cocaine and cannabis resin through the south of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly in the province of Cádiz, from the town of Barbate to Punta Caraminal, leading to an increase in violence against law enforcement (Passolas, 2018). For example, two agents of the Guardia Civil were murdered by a narco-boat in Barbate in February 2024 (Cañas, 2024) and clandestine groups continue to operate in the area, such as Los Castaña and Los Pantoja (Serrano, 2024).

It is well known that the main source of cannabis resin consumed in Europe comes from northern Morocco, where production levels are at an all-time high, even though its trade is illegal, and it is estimated that there are more than 55,000 hectares under cultivation. (Palomino, 2023) and it is estimated that there are more than 55,000 hectares under cultivation, with illicit trafficking by sea and road (Erhardt, 2023) with illicit trafficking by sea and road to the continent. According to the reports of EUROPOL's Serious Organised Crime Threat Assessment (SOCTA), cannabis resin originating in Morocco is also increasingly being trafficked across the Mediterranean Sea from Libya, a country that has been embroiled in internal conflict for years. Shipments of cannabis resin are transported across the Mediterranean Sea to the Spanish coast with high-powered boats, where they are dumped at sea and recovered by criminal organisations on local fishing or recreational boats with geo-tracking devices. (EUROPOL, 2024)

In recent years, several events have also demonstrated an increase in the impact of organised crime in Central and Northern Europe, especially in the Netherlands, such as the notorious Mocro Maffia, so called because of the Moroccan origin of the Dutch members of the criminal organisation (RTVE, 2023). The group uses traditional cannabis resin trafficking routes to smuggle cocaine into the Netherlands and other central European countries and has even been covered in international press after it threatened the Dutch royal family and prime minister (Stroobants, 2022).

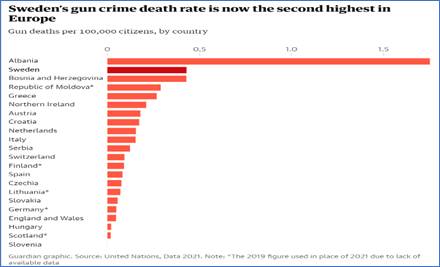

Another country that has recently seen an increase in the impact of organised crime is Sweden. Most organised crime groups and gangs in Sweden are dominated by non-ethnic Swedes, from the Balkans and the Middle East, among other regions. According to the data analysed (Tomlinson, 2023), foreign-born persons and their progeny are significantly over-represented in crime, while foreign groups not based in Sweden, mainly from Eastern Europe, enter the country to commit robbery and theft. Organised Roma groups are also becoming more frequent. However, internal criminal networks continue to dominate areas of Swedish cities, making Swedish society less and less safe, including shootings in public areas due to clan rivalries that call into question the Swedish state's ability to control such situations (DW, 2022).

All these and other similar examples show how organised crime groups, mainly active in drug trafficking, have made a qualitative leap, confronting the structures of certain states and abandoning the usual more discreet profiles of organised crime. This paper aims to investigate the evolution of this trend, and to propose resistant solutions in the medium to long term on the basis of the lessons learned and shared in the framework of the official Master's Degree in Senior Management in Security (MADSI), offered by the Centro Universitario de la Guardia Civil, in which Spanish-speaking public and corporate security managers with extensive professional experience in the areas of study of this research participate.

2. THE CONCEPT OF ORGANISED CRIME AND ITS RELATION TO TERRORISM

The first international reference to organised crime is found in the 2000 United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime, known as the Palermo Convention, which defines an organised crime group as "a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences established in accordance with the Convention in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit". Serious crime means "conduct constituting an offence punishable by a maximum prison sentence of at least four years or a more serious penalty". And structured group is defined as "a group not formed incidentally for the immediate commission of a crime, and in which its members have not necessarily been assigned formally defined roles or continuity of membership or a developed structure" (ONU, 2000).

The concretisation of these concepts in a public international law instrument of broad consensus is essential for an effective fight against this type of criminal phenomenon, as it allows the introduction of these concepts in the national legislations of the States, favouring the processes of police and judicial cooperation at the international level in the prosecution of organised crime. For example, with the application of the principle of mutual recognition in extradition processes of criminals related to this type of crime, in the use of controlled delivery of drugs in transit between countries, or in the use of special investigative techniques in these countries, as set out in Article 20 of the aforementioned Convention.

In addition to this definition, we can also refer to the criteria established by EUROPOL standards to identify this type of criminality, which require the following main characteristics:

· The collaboration of two or more people.

· Prolonged action over time.

· The commission of serious crimes.

· The pursuit of economic gain or power.

However, in addition to the above criteria, at least two of the following indicators must be met:

· Specific distribution of tasks.

· Use of some form of internal control.

· Extension to the international arena.

· Use of violence.

· Money laundering.

· Use of financial or commercial structures.

· Corruption of public authorities or companies.

The Palermo Convention was signed by 189 states and, therefore, the concept of transnational organised crime can, as we note, be considered almost universal.

In attempting to analyse the concept of terrorism and its relationship with organised crime as set out in the heading, we note that we do not have a globally accepted legal definition of the concept of terrorism. In seeking the first legal approximations to the concept of terrorism at the international level, we must recognise the difficulties that have existed in the international community in arriving at a unanimous definition of the subject. The efforts made within the United Nations have not been definitive so far, because although the international organisation itself recognises the existence of various international conventions and instruments related to terrorism developed within the framework of the UN[1], none of them expressly define terrorism or terrorist acts. Despite the fact that some EU Member States, to a greater or lesser extent, as is the case of Spain, had been suffering from the actions of terrorist groups of various kinds, such as ETA in Spain since the 1960s, the goal of fighting terrorism in a common, specific and differentiated way would not be fully identified in EU policy and legislation until the attacks of 11 September 2001 in the USA.

This first change of attitude is identified in the Conclusions and Action Plan of the Extraordinary European Council of 21 September 2001, which met in extraordinary session just ten days after the attacks to analyse the international situation and give the necessary impetus to EU actions, establishing a few days later the Council Common Position 2001/931/CFSP of 27 December 2001 on the application of specific measures to combat terrorism, which in turn represents the first specific supranational common identification of the concept of terrorism by an international organisation. Terrorist acts are defined as "intentional acts that may seriously damage a country or international organisation by intimidating its population, imposing all kinds of hardships, and destabilising or destroying its fundamental constitutional, social and economic structures" (EURLEX, 2001).

The text indicates the criminal nature of these terrorist acts by stressing that the mere threat to commit one of these offences should be considered a terrorist act. The identification of the concept of terrorism in European Union law underwent a second essential step forward the following year, in 2002, with the Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA of 13 June 2002 on combating terrorism, which has the essential purpose of inviting Member States to approximate their legislation and establishes common rules on terrorist offences. The concept of terrorism and terrorist acts has undergone a thorough update, through the Directive (EU) 2017/541 of the Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on combating terrorism, replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA and amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA, establishing the common definition of terrorism and terrorist acts for all EU Member States. Therefore, we can conclude that, without currently having a global legal definition of the concept of terrorism or acts of terrorism, the most widely applicable legal reference is that understood and applicable in the 27 EU Member States.

We can conclude from this analysis that, in the legal conceptualisation of the concept of terrorism, its purpose is not essentially financial, as in the case of organised crime, but rather to force changes in political systems through intimidating, violent or destabilising actions. In addition, terrorist groups seek to spread their aims through spectacular criminal actions that cause terror, whereas organised crime does not normally seek to draw attention to itself in pursuit of its financial aims, in order to avoid justice. In this context, on 19 July 2019, the UN Security Council of the United Nations adopted Resolution 24824 on the links between international terrorism and transnational organised crime. It shows that terrorism and organised crime also have little in common intellectually, as the former is based on radical and violent interpretations of ideologies or religions, while the latter is based on the pursuit of financial gain or, sometimes, the control of power to obtain it. However, one can use the modus operandi of the other. Terrorists will engage in organised crime to finance their operations, and organised crime can use terror to achieve its ends, including by confronting the State, as we have seen above.

3. SITUATION AND TREND ANALYSIS

3.1. THE US-MEXICO BORDER

In the US, there are several historical and current references to organised crime groups such as Polish-American and Greek-American organised crime, the Assyrian Mafia and Hawaiian criminal organisations. Also, the well-known Italian-American criminal organisations; the Jewish Mafia; African-American organised crime; the Irish mobs; or the criminal groups linked to the countries of the former USSR (Wright, 2013). Particularly relevant is the criminal problem in the US-Mexico border area, where organised groups operating on both sides of the border engage in human trafficking, mainly drug trafficking from south to north and arms trafficking from north to south (Badillo, 2023). Their modus operandi has continued over time, such as, in the latter case, the shipment of weapons of war in pieces or as a whole (Montalvo, 2016) through so-called "ant" traffic with postal courier services, (Flores, 2022)among other ways, coming from the US military (APNews, 2024) and being an illicit traffic institutionally recognised by the authorities of both countries. (Ejecentral, 2023)

In the field of drug trafficking, in addition to the well-known trafficking of cocaine from producer countries through Central America and other routes, (Guevara, 2021)in recent years, the illicit trafficking of fentanyl from China through the ports of Manzanillo and Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico has gained prominence, causing alarm in the USA (Cano, 2023). But as has also been indicated, organised crime is present in human trafficking on the US-Mexico border, with an increase in the number of people from Central American countries and other parts of the Americas trying to reach the US to find better living conditions, fleeing poverty and insecurity caused mainly by organised crime in their countries of origin (Parker, A. y Dudley. S., 2023).

The organised crime scenario in Mexico is complex, first of all, a reference to the so-called Guadalajara Cartel, which can be considered the first major drug cartel in Mexico, from whose leaders many splinters subsequently emerged. First, the Gulf Cartel, estimated to be the oldest Mexican criminal syndicate from which Los Zetas, La Familia Michoacana, and the Caballeros Templarios are drawn. Secondly, the Sinaloa Cartel, also spawned from the Guadalajara Cartel, and from which in turn the Colima Cartel, practically dissolved together with the Sonora Cartel, is derived. Another criminal group that appears to be linked to the Sinaloa Cartel is the so-called Gente Nueva, or a kind of cell of the Sinaloa Cartel in Chihuahua. The Beltrán-Leyva Cartel, formerly part of the Sinaloa Cartel federation and later independent, is also known as a splinter of the Guadalajara Cartel. In this last powerful organised crime syndicate, we identify mainly, although not exclusively, the Cártel del Pacífico Sur in Morelos; the Cártel del Centro in Mexico City, or the Cártel de Acapulco, also with origins in the Cártel Beltrán-Leyva; La Oficina, in Aguascalientes; the Cártel de la Sierra, in Guerrero; the Cártel de la Calle, in Chiapas; or Los Chachos, in Tamaulipas. Not to mention the Cártel de Tijuana, which also emerged from the Guadalajara Cartel, and its split into the Cártel de Oaxaca. Finally, mention should be made of the notorious Cártel de Juárez, spawned from the Guadalajara Cartel and with its own hit squads such as La Línea o Barrio Azteca (Marley, 2019).

As we can see, the impact of organised crime is diverse and varied, especially on both sides of the US-Mexico border, with a presence also in many areas of the country, and directly related to high levels of violence that even challenges the State with heavily armed militias as in the aforementioned culicanazo, and numerous cases of judicial and public security corruption, which even led to the reform of the police system in the country as of 2019 (Ferri, 2024). There seems to be no magic solution in the short term, nor can one be found through isolated policies to increase or reform public security forces if they are not accompanied by comprehensive reforms in the security and justice sector, and by a greater state presence that is sustained over time and resistant to corruption, with the allocation and management of public funds that improve people's quality of life, especially in depressed areas where organised crime has its breeding ground.

3.2. CENTRAL AMERICA

In Central America, the phenomenon of organised crime stands out through the so-called maras, or violent gangs, the presence of which is attributed to El Salvador, but which extend throughout the region, such as in Honduras and Guatemala, and also at the international level. These organisations were born in Los Angeles (USA) in the 1980s and are mostly made up of young people. Very few of its members are over 30 years of age. The main maras are Mara 18 and Mara Salvatrucha, or Mara 13, which are now at loggerheads with each other and with numerous splits. They are known for using crime-related tattoos all over their bodies, sign language, and above all extreme violence, having been confronted by other criminal groups such as the Mexican cartels for settling scores (ERIC-Group, 2001).

Particularly significant in this area is the public security policy promoted by the Bukele government in El Salvador at the end of 2022, following a sharp increase in homicides and territorial control by the maras. A regime of exception has been promoted on the basis of Article 29 of the country's Constitution, which has allowed for state control of the territory, a high number of arrests of gang members, not without allegations of torture, and a reduction in the homicide rates caused by these organised crime groups (Avelar, 2023)... This has undoubtedly contributed to the re-election of its president in the February 2024 elections with 85% of popular support (Vozpópuli, 2024). Indeed, the situation has changed in El Salvador and from being a country known for high rates of violence and control of territory by organised crime, it has become a safer country, which is beginning to attract tourism to a greater extent, (Abarca, 2024) and which serves as a reference for other governments on the continent that are suffering public security crises caused by organised crime, such as Ecuador (Ejecentral, 2024) or Argentina(ABC, 2024). But the challenge is to maintain the situation in the long term. Improved public security, achieved mainly through greater powers for the police and armed forces in the country, may have a short-term effect, but it will not be sustainable if not accompanied in the medium and long term by public investment policies, especially in depressed areas, with improvements in infrastructure, schools, hospitals, construction of public housing, improvements in salaries, etc., as mentioned above, in a corruption-resistant manner.

3.3. THE CASE OF HAITI

The case of Haiti is particularly paradigmatic as it is considered one of the countries in which organised crime, especially related to drug trafficking, has managed to infiltrate and eventually completely destabilise the structures of a State. Since around 2000, armed gangs linked to the drug trade have been increasingly occupying the public sphere, to the extent that notorious drug trafficking figures have been standing in parliamentary elections to directly defend their interests (Maesschalck, 2020). It is estimated that international intervention after the 2010 earthquake did not have the desired effects either, merely delaying the collapse of the Haitian narco-State. In this context, drug-related gangs control territory, and demand payment entitlements from the population. Public office is bought, with high levels of corruption and a real absence of state structures. (Becker, 2011)

It seems clear that the country has long been in need of shock therapy to help re-establish the structures of the state, similar to what has taken place in El Salvador, which will gradually evolve towards a situation of normalised stability for the benefit of the population.

3.4. COLOMBIA

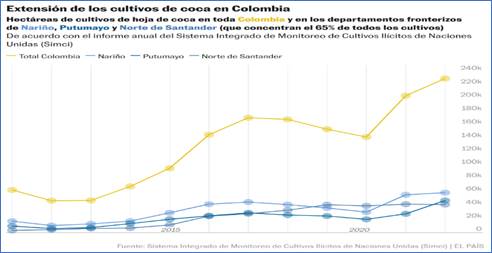

For many years, Colombia has suffered the scourge of terrorism by guerrilla groups such as the FARC and the ELN with the aim of imposing governments with a Marxist-Leninist political orientation by means of violence and terrorist attacks (Buitrago, 2022). The dissolution of the FARC terrorist group in 2016 following the Havana Accords, with the announcement of talks with the Government in 2014, coincided with a progressive increase in coca leaf cultivation, as shown in the following graph, which peaked in 2022 with an estimated 230,000 hectares under cultivation (UNODC, 2023).

Figure 2.

Extent of coca cultivation in Colombia

Despite the agreements reached, the increase in production is related to the progressive dismantling of the FARC as a terrorist group, and the transformation of a large part of its armed militias accustomed to controlling parts of the territory, and a way of life that is difficult to change, into organised crime groups devoted to drug trafficking (UNODC, Colombia: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos, 2021). In addition to the abandonment of more effective, albeit controversial, eradication policies such as the use of herbicides in aerial spraying, (Torrado, 2022) which also avoided the painful manual eradication processes that have caused so many victims due to booby traps set by drug traffickers (Meneses, 2008). As we can see, Colombia continues to be the main producer of coca leaf, as well as cocaine hydrochloride. Although major organised crime groups such as the Clan del Golfo, among others, are still present, the main historical actors in drug trafficking, like the Cartel de Cali of the Ochoa brothers, or the Cártel de Medellín with Pablo Escobar in the 1980s, have disappeared due to state action. In Colombia, a positive development has been sustained public investment over time and greater resilience to corruption in depressed areas, such as the Comuna 13 in Medellín, a former fiefdom of Pablo Escobar and now an alternative tourist area (Moreno Segura, 2023). Despite the existing difficulties, this can serve as a benchmark for the application of corruption-resistant moderate public policies, including public security policy, which after more than 20 years of sustained application have managed to defeat or at least contain drug trafficking.

3.5. VENEZUELA

In Venezuela, organised crime is particularly prominent through the control of prisons, as in the case of the so-called Tren de Aragua and its extension throughout the Americas. El Tren de Aragua is the most powerful criminal structure in Venezuela, and the only local group that has managed to gain a foothold abroad. No longer a prison gang confined to Aragua State, it has become a transnational threat with a broad criminal portfolio (Insightcrime, 2023). Organised crime associated with the Tren de Aragua has spread to several Latin American countries, especially Chile. The organisation was detected two years ago by Chilean prosecutors investigating migrant smuggling, sexual exploitation, murder, torture and drug trafficking(Sanhueza, 2023). Furthermore, in Venezuela there are also references to the relationship of some members of the country's armed forces with drug trafficking through the so-called Cartel de los Soles (Cartel of the Suns) (Delgado, A. y Lares, V., 2022). Therefore, this situation constitutes an empowerment of organised crime with infiltration of state structures, such as the prison system or the armed forces.

3.6. ECUADOR

Ecuador is not traditionally a major producer of coca leaf due to its own geographical conditions, despite having borders with the main coca producing countries of Colombia and Peru. Organised crime has turned one of the country's main ports, Guayaquil, into an intentional centre for drug trafficking, and it has been supplied by organised crime groups from other countries, such as Albanian clans among others (Arroyo, 2023).

In the introduction, we also mentioned how organised crime groups in Ecuador have become empowered and problems, mainly relating to a lack of control of prisons, have been arising for some years (BBC, 2023). As analysed, the pulse of organised crime on the State is being confronted by the current administration with special measures such as the declaration of an internal armed conflict in January 2024 by the President of the Republic, with indications of a reference to the Bukele model and its application in Ecuador (Basantes, 2024).

There is no doubt that every country and its administration is sovereign when confronting serious threats to public security, and that the latest news from Ecuador points to a change in the trend of state action in relation to organised crime. As in the case of El Salvador, it seems logical to think that the administration's desire, once the situation has stabilised, is to accompany the public security policies implemented with reforms in the justice sector and the development of public policies that are effective, lasting and as far as possible free of corrupt practices, especially in the area of prison control.

3.7. PERU

Peru, the second-largest producer of coca leaf after Colombia, with approximately 95,000 hectares in 2022 as we saw in Figure 1, has also seen an increase in coca leaf cultivation, and, therefore, in cocaine production, which ultimately reaches the international market through organised crime, mainly via Ecuador and Brazil. The main production area is the so-called VRAEM, short acronym for the Valley of the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro rivers, where important institutional efforts have been made in eradication campaigns. (Aleteia, 2019). This area accounts for an estimated half of the country's cocaine production and is considered the main area of action of the dissidents of the terrorist group Shining Path, which for decades tried to impose a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist state through terrorist attacks (Jímenez Vigara, 2019), leading to more than 60,000 victims. After its dismantling with the fall of its leader Abimael Guzmán, remnants of this terrorist group still control a large part of the production and distribution of cocaine in the VRAEM (Cueva López, 2015).

The political instability in the country in recent years has not helped in the development of sustainable public security policies over time, but at least the professionalism of the judicial and police system in Peru, which is trying to contain the problems of the VRAEM, has made it possible to maintain lower crime rates in the country than in neighbouring countries, such as Chile and Bolivia (ONU, 2023).

3.8. BRAZIL AND THE TRIPLE FRONTIER

In Brazil, there are powerful urban criminal organisations, with a strong presence in the favela areas of the big cities, such as the Red Command in Rio de Janeiro, or the First Capital Command in the State of São Paulo, but with implications in other areas of the country, and even related to illicit drug trafficking to other continents (Quirós, 2019). The hot zone of Brazil and its triple border with Paraguay and Argentina, through which the aforementioned criminal groups, among others, traffic cocaine, mainly from Peru and Colombia, is also important (Ojopúblico, 2023). Well-known criminal organisations operating at the international level also carry out their illicit activities in this area in relation to the supply, trafficking and subsequent retail sale in Argentinian markets, or for shipment by sea to markets in Africa and Europe. Consequently, they are in charge of the shipments that are introduced into Argentina from Bolivia or Paraguay by air via the so-called "white rains" or through the more than 500 clandestine airstrips existing in that country(Prado, 2016).

Brazil is a continent-sized country with porous and difficult-to-control borders in the Amazon with coca-leaf-producing countries such as Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. There are high levels of crime and police corruption in large urban areas(InSightCrime, 2017) and powerful criminal groups, which, without putting state structures at risk, are major players in international drug trafficking, mainly through Africa (Zupello, 2023), illegally obtained mining (Efeverde, 2023)or of protected species (Europapress, 2020)

3.9. TERRITORIES USED FOR MONEY LAUNDERING. PANAMA, URUGUAY AND THE FORMER BRITISH COLONIES

But the American continent also has certain countries and territories with entities specialising in laundering the proceeds of, among other things, the illicit activities of organised crime. We are referring to countries such as Panama (Berlinguer, 2016)where, in addition to cases of money laundering with a global impact, such as the well-known Panama Papers (BBC, 2016), the country's banks have also been used by drug trafficking-related organised crime (Rognoni, 2024). Similarly, certain areas of Uruguay, such as Punta del Este, which is considered by some authors to be an important centre for laundering drug trafficking proceeds, have also been the scene of numerous drug money laundering operations (Lucena, 2023).

But, above all, it is the British colonies in the Caribbean that stand out as tax havens according to international benchmarks. Territories such as the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas and the Cayman Islands are well-known offshore territories that have long been used by drug traffickers for money laundering, even corrupting the highest levels of government, as in the case of Andrew Fahie, former prime minister of the British Virgin Islands, convicted in the USA for drug trafficking, corruption and money laundering (Voss, 2024).

3.10. THE SITUATION IN AFRICA

It is not easy to try to summarise the complexity of the African world and its relationship with organised crime. But in a general way, we can identify the main scenarios and incidence of organised crime therein. Firstly, a large area close to the Mediterranean in the Maghreb and the Middle East where organised crime groups engaged in a wide variety of illicit trafficking to the EU, in some cases also linked to terrorism, converge. (Martínez, 2017).

Moreover, the large Sahel area with countries such as Mali, Niger, Chad, Sudan and South Sudan, countries with porous borders in which organised crime groups are also involved in various illegal trafficking activities, including arms trafficking and their relationship with Islamist terrorist groups such as Boko Haram and Al Sabah (UNODC, Firarms trafficking in the Sahel, 2023).

The countries on the Atlantic side of West Africa, such as Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, etc., are weak states with a lack of port control (Darren, 2021). This circumstance is used by organised crime groups such as those led by the Malian-Moroccan El Hadj Admed Ben Brahim, known as the Pablo Escobar of the Sahara, who specialises in introducing cocaine into the aforementioned ports in the region and transporting it via the Maghreb routes to Europe (Kabbaj, 2024).

The area of the Gulf of Aden and the coast of Somalia is an area known internationally for the practice of piracy (Esglobal, 2016).

Central Africa, with countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, where strategic minerals are illegally produced and traded in the context of an ongoing conflict zone (Sánchez Moreno, 2021).

Lastly, the southern zone with the violent South African criminal gangs known as the number gangs, named after the numbers by which prisons are identified in South Africa (Velázquez, 2013). As a specific case, we should also mention the so-called Nigerian gangs that mainly engage in organised frauds known as 419 scams or Nigerian letters (Sánchez Oliveria, 2023).

3.11. TRENDS IN EUROPE

As indicated in the introduction, in recent years, several reports have shown an increase in the impact of organised crime in central and Northern Europe, mainly in the Netherlands, for example with the so-called Mocro Maffia, and also, according to the aforementioned EUROPOL SOCTA reports, the increase of criminal groups specialising in the production and commercialisation of synthetic drugs in Germany, Poland and Slovakia.

We also saw how certain Northern European countries, such as Sweden, unaccustomed to the notoriety of organised crime, have suffered an increase in recent years in the activities of this type of drug trafficking-related criminality, leading to changes in the trend in this area, making Sweden the second country in Europe with the highest number of violent deaths related to criminal gangs, as shown in Graph 3 below, well above the figures that this country had been suffering in previous years.

Figure 3

Violent deaths in Europe due to organised crime (UN)

Furthermore, taking as a reference the most recent information available from open sources, we observe cases such as that of Spain, in which organised crime in Galicia has taken on a more discreet profile in recent years, unlike the previously known Galician clans dedicated to drug trafficking and cigarette smuggling with connections in Latin America, such as Los Charlines; Os caneos, Clan de los Fernández; Clan Oubiña; Os Romas; Os Piturros; Os do Barbanza; Os Pulgos, etc. (Méndez, 2018). However, practices have also been detected in the trafficking of cocaine to Europe that were not common until very recently, such as the use of submarines off the Galician coast. (Ortega Dolz, 2019).

As we saw initially, Spain also suffers from Mafias specialising in cannabis resin trafficking in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly in the province of Cádiz, with an increase in violence against security forces (Passolas, 2018) and the continued presence of criminal clans in the area, such as Los Castaña and Los Pantoja (Serrano, 2019). Cocaine trafficking through ports such as Algeciras and Valencia should also be mentioned (Chaparro, 2019). In addition to the aforementioned port of Algeciras, the port of Valencia has taken centre stage due to the large annual movement of containers, making it very difficult to effectively control them, and, therefore, making it possible to detect illicit trafficking declared as other types of merchandise (Ordaz, 2018). There are even some publications that claim that criminal organisations with connections to Colombian drug traffickers are settling in the Gibraltar area and have been using the nickname "Little Medellín" for some years now (ABC, 2018). Even more recently, new cocaine trafficking routes have emerged in this area (EUROPASUR, 2024). Nor does the existence of the enclave of Gibraltar, which can be considered a true tax haven where other illicit trafficking, such as cigarette smuggling, also converges, make the fight against organised crime and corruption any easier (Ortega Doltz, 2015). We should also mention that there are numerous criminal organisations with members from different countries such as the British, Irish, Swedes, etc., who engage in illicit drug trafficking, which are being dismantled in the south of Spain and especially on the Costa del Sol (Clarkson, 2010).

4. STUDY OF POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS. CONCLUSIONS

Obviously, there are no quick, magic solutions to the increased threat of organised crime related to drug trafficking that we have analysed, and with this reality in mind, the following is a study of possible comprehensive solutions based on the analysed arguments that can be developed in the medium or long term as state policies and strategies that contribute to changing the situation of empowerment of criminals for the benefit of citizens. We reflect below on the feasibility of some of these solutions, as indicated, by way of conclusions.

4.1. THE LEGALISATION OF DRUGS AND ITS POSSIBLE IMPACT

Legalising drugs is a commonly suggested solution to the problem of drug trafficking and the insecurity and instability associated with this variety of organised crime, among others. But the solution is not so simple. If we look at the case of the Netherlands, after more than 30 years of anti-global drug prohibition policies, the country reports levels of soft drug use below the European average. But the evidence shows that these policies are far from ideal, as they have spill-over effects (Bugari, 2010). Indeed, the authorities decriminalised the sale and consumption of soft drugs, but not their production, so that the so-called coffee shops are supplied by criminal circuits, which also have logistics and experience in so-called laboratory drugs. This has made the Netherlands the world's largest producer and exporter of synthetic drugs, providing the organised crime groups involved with hefty profits, as certain authors (Hernández, 2019) and the SOCTA EUROPOL reports themselves point out.

4.2. ERADICATION OF PLANTATIONS WITH NATURAL HERBICIDES AND EFFECTIVE SUPPORT FOR SHIFTING CULTIVATION

It seems illogical to think that with the advances in science and technology in the 21st century, where it is possible to know the exact location of plantations of crops, including coca leaf in producer countries, and where herbicides are available to control this type of crop, these crops have not stopped growing in the last decade. When we delve deeper into this type of solution, we see that certain governments over the years have tried to eradicate this type of crop through aerial spraying with synthetic herbicides such as glyphosate, with effective results, but not without controversy due to its alleged harmful effects on the population and the environment. This despite the fact that it is a herbicide widely used across the world for all types of crops, and also because of the impact on local communities who may see an ancestral way of life disappear, linked to the cultivation of coca leaves, even though this type of traditional crop and those dedicated to industrial use represent only 10% of production (Montaño, 2022). Certain governments in Colombia have also attempted to eradicate the coca leaf plant manually, with less effective results, and the penalty of suffering numerous casualties among the personnel hired to do this, due to the strategy used by drug traffickers of mining or setting up booby traps in the areas close to the plantations. (GOV.CO, 2023)

Given this situation and with record levels of coca leaf hectares, perhaps it is time for international organisations to demand and support the main coca leaf producing countries to develop effective policies against coca cultivation, through aerial spraying with natural herbicides such as EDEC, supported by crop shifting measures for traditional producers (García Bravo, A, De Hoyos, K, y Fernández Ramírez, Oscar Eduardo, 2018).

4.3. EFFICIENT, SUSTAINED AND CORRUPTION-RESISTANT PUBLIC INVESTMENT IN DEPRIVED AREAS

There are many deprived areas developing in large pockets of population in a number of countries that are heavily affected by organised crime. People flee poverty, lack of opportunity and subhuman living conditions, including insecurity caused by organised crime. We have seen that there are communes, favelas or neighbourhoods where the State is absent, and where organised crime, especially related to drug trafficking, imposes its own rules. We already know that there are no quick solutions, nor are they problem-free, but we have also learned first-hand about certain examples that can serve as references for other countries, such as the aforementioned case of Comuna 13 in Medellín (Colombia), where, after years of corruption-resistant public investment policies sustained by governments of different political colours, an area of the city controlled by drug trafficking has been transformed into a habitable and visitable area with a strong State presence.

4.4. ARMS CONTROL

We have seen how arms trafficking, especially from the US, with specific regulations on easy access to weapons of war for the population, and their destination to the rest of the Americas through the Mexican border, has undesirable effects, such as the existence of organised crime groups with access to large-calibre weapons with which to confront the State. Indeed, there is little oversight when it comes to selling an assault rifle in the US without a criminal or police background check, or even a minimum check of the buyer's mental health, which undoubtedly has an effect on the numerous gun incidents in the country, with more than 20,000 deaths from gun violence by 2023. (GVA, 2024)

As already mentioned, the legal regulatory framework that a given country can establish for the production and sale of arms and explosives is not in dispute, but there is also no doubt that greater control of arms sales, such as that occurring in Spain by the Guardia Civil with files for each case, with the criminal record of the potential buyer and their state of mental health, would limit mass access to arms by citizens, violent incidents involving arms, and above all organised crime and its capacity to confront state structures with weapons of war, as occurs in so many countries in the Americas.

4.5. PRISON DISPERSAL POLICY. CONTROL OF PRISONS

There are several cases in which organised crime has been able to completely or partially control the prison system in certain countries such as Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador. Nor, as in previous cases, are there any formulas for a solution beyond the effective control of the penitentiary system by the state, investing in facilities, personnel and resources, but above all in the development of mechanisms for the control and dispersal of prisoners, such as those developed in Spain in its fight against the terrorist group ETA, which prevent organised crime groups from continuing to direct and control drug trafficking from prisons.

In this context, we can observe the development of possible solutions in certain countries, such as in El Salvador, with penitentiary policies based on the construction of large prisons and the application of exceptional systems (Dammert, 2023), which, although they may be temporary solutions to confront extreme situations of increasing violent organised crime in certain countries, require the development of sustainable medium- and long-term policies aimed at returning to situations of stability and normality.

4.6. EFFECTIVE REGULATION OF TAX HAVENS

Numerous national and international efforts are being made to implement effective anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing standards, and an increasing number of institutions are obliged to report suspicious transactions in this area. However, the international community and, therefore, international organisations have still not effectively limited the operation of tax havens and their use by organised crime for laundering drug trafficking proceeds. Indeed, each state or territory is free to legislate its own taxation regime, but it also seems clear that if we really want to fight drug money laundering, international regulators must require these territories to be transparent and collaborate effectively when there are requests from courts in other countries.

4.7. EFFECTIVE MULTILATERALISM IN AFRICA

UN and EU projects, among other international actors, have been trying to bring stability to several African countries affected by regional conflicts, poverty, political instability, corruption, terrorism and organised crime, exploiting the weakness of these states to make profits mainly through illicit trafficking. The instability of areas such as the Sahel, with numerous coups d'état in a short period of time in recent years, and the increasing influence of unilateral actors such as Russia and China in the region, highlights the crisis of multilateralism promoted by international organisations, especially the EU.

Security sector reform projects such as GARSI SAHEL (CasaAfrica, 2024), which involve the training and development of the combined capacities of robust police units with reinforced equipment and criminal investigation units following the model of the Rapid Action Group (RAG) and its experience in Spain in the fight against ETA, undoubtedly contribute to strengthening the states in the area and creating better security conditions with units that have the motivation and preparation to confront major threats such as terrorist or organised crime groups, which, like militias, control parts of the territory. But such security sector reform initiatives will not have a lasting effect unless they are part of a comprehensive reform of State institutions by local actors, making them more resistant to corruption through the development of public policies that truly reach the people and enable the creation of opportunities at the local level with peace and security.

4.8. IMPROVING POLICIES AND STRATEGIES AGAINST DRUG-RELATED ORGANISED CRIME IN EUROPE

We have already seen that improving the fight against drug trafficking does not only depend on the existence of appropriate and effective structures in the security forces, but also on the development of public policies with a State vision that are sustainable over time. Some possible improvements in this regard are outlined below.

4.8.1. Public investment policies in areas affected by drug trafficking

The experience of the evolution of drug trafficking in certain areas such as the Campo de Gibraltar in Spain or the Comuna 13 in Medellín (Colombia) shows that in addition to improving the judicial and police systems, it is necessary to develop public investment policies that are sustained over time and resistant to corruption in order to improve education, industry, commerce, infrastructure and, in short, the existence of opportunities in depressed areas that are particularly affected by drug trafficking.

4.8.2. Greater control at ports

Along with the increase in international trade, we are witnessing the development of large ports such as Rotterdam in the Netherlands, Gioa Tauro in Italy, Antwerp in Belgium, and Valencia or Algeciras in Spain, which are increasingly used by organised crime for its illicit trafficking operations, mainly related to drug trafficking. On the other side of the Atlantic, we have already analysed the relevance of other ports such as Guayaquil in Ecuador or Manzanillo in Mexico in drug trafficking. Another solution that can contribute to combating this empowerment of organised crime must come from the implementation of organisational and technological measures, which, without interfering in commercial traffic, allow for greater control of these types of ports, which are, after all, critical infrastructures that must be controlled by States.

4.8.3. Improving investigative and judicial capacities against organised crime

Organised crime has a great capacity for corruption and for threatening the frontline judicial and police authorities in the localities where drug trafficking takes place. A good practice that has proven effective in the fight against this type of criminality has been creating courts and central units geographically separated from the areas mainly affected by drug trafficking, but with the capacity to deploy sustained investigative capacities in these areas, without feeling the pressure of the criminals, empowering these bodies with effective personnel and resources. Examples of this type of action can be found in the central investigative courts of the Audiencia Nacional or the Unidad Central Operativa (UCO) of the Guardia Civil's Judicial Police in Spain.

4.8.4. Sustained joint operations against organised crime

The development of sustained joint police operations against organised crime has proven to be an effective solution against the establishment of organised crime in certain areas or territories. The deployment of special operations units working together with criminal investigation and intelligence specialists and prosecutors in a sustained manner over time with the establishment of command and control structures has proved effective, such as Operation Agamemnon carried out by the Colombian National Police (Espectador, 2021) or Operation CARTEIA, launched by the Guardia Civil against drug trafficking in the Campo de Gibraltar. (Clemente Castrejón, 2022)

4.8.5. Efficient interoperability of information systems

Lastly, an effective fight against organised crime necessarily involves avoiding corporatism between institutions within the same country and at the international level, and effective cooperation in the exchange of information and criminal intelligence. There is no other option than the necessary real interoperability of information systems as advocated by international organisations such as the EU, establishing mandatory rules for States such as the provisions of Directive (EU) 977/2023 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 on the exchange of information between law enforcement authorities of the Member States, repealing Council Framework Decision 2006/960/JHA.

Indeed, Council Framework Decision 2006/960/JHA of 18 December 2006 on simplifying the exchange of information and intelligence between law enforcement authorities of the Member States of the European Union stated in its preamble that "Currently, formal procedures, administrative structures and legal obstacles in Member States' legislation are severely limiting the rapid and effective exchange of information and intelligence between law enforcement authorities. This situation is unacceptable for the citizens of the European Union, and, therefore, calls for greater security and more efficient policing, while protecting human rights".

As Directive (EU) 977/2023 acknowledges, little progress has been made in effective international law enforcement cooperation relating to the exchange of information and intelligence because of the problems outlined above, but especially because of the lack of real cooperation in the exchange of information between entities within Member States. It is clear that in order to comply with the guidelines established at the EU level and to be able to cooperate at the international level, it is first necessary to cooperate at the national level, beyond the corporatism of police or customs entities.

5. FINAL ASSESSMENT

Research shows a change in the trend of organised crime, mainly related to drug trafficking, at the beginning of the 21st century. Drug production and confrontation situations are at record levels, as is the infiltration of the institutions of various States that were previously not prominent in this type of profit-driven crime, which seeks not to attract too much attention from the authorities.

We can also observe how certain governments are incapable of containing or even collaborating with organised crime, contributing to the instability of States, to the lack of public services and, in short, to the population of these countries becoming demoralised due to organised crime and corruption affecting their daily lives.

Extreme situations of empowerment of organised crime with skyrocketing rates of violence, such as that occurring in El Salvador, have led certain administrations to opt for exceptional measures, which, although not without controversy, seem necessary and temporary to re-establish the presence of the State. This model is spreading across the Americas to other countries suffering similar situations, such as Ecuador, or certain areas in Argentina.

Undoubtedly, the fight against organised crime should not be limited to police action, which is a major but not sufficient player in solving the problem. It is believed that the problem of organised crime must be tackled through State policy, and with strategies based on an adequate allocation of resources in a sustained manner that, based on respect for people's fundamental rights, goes beyond the short-term vision of a four- or five-year term in office to become a true State policy independent of political colour and resistant to corruption.

This fight will not be complete if international organisations do not demand and support states in the development of these policies, and above all a more effective regulation of offshore territories related to the laundering of drug-trafficking proceeds.

As stated in chapter 4, the author's conclusions refer to possible medium- and long-term solutions, which have taken into account the analysis of the sources mentioned, but also the invaluable learning experience of directing the official Master's Degree in Senior Management in International Security, made up of 60 European credits taught by the Centro Universitario de La Guardia Civil, which has had the support of judicial and police authorities from Argentina, Colombia, Brazil, Chile, Peru, the United States of America, Honduras, Ecuador, and EU countries since its implementation in 2019, to whom this research article is dedicated with great affection, fondness and gratitude.

Aranjuez, 9 June 2024

6. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Council Framework Decision of 13 June 2002 on combating terrorism (2002/475/JHA).

Abarca, M. (2024). "Repunte del turismo de El Salvador impulsa al sector en Latinoamérica". https://diarioelsalvador.com/repunte-del-turismo-de-el-salvador-impulsa-al-sector-en-latinoamerica/462361 Access 10.02.2024

ABC. (2018). “ Narcos colombianos desembarcan en el campo de Gibraltar”. https://www.abc.es/espana/andalucia/cadiz/sevi-narcos-colombianos-desembarcan-campo-gibraltar-201805030725_noticia.html Access 10.02.2024

ABC. (2024). “Argentina comienza a emular estilo bukele”.

https://www.abc.es/internacional/argentina-comienza-emular-estilo-bukele-carceles-20240307091010-nt.html Access 08.03.2024

Aleteia. (2019). “Perú: Cruzada contra la hoja de coca en VRAEM, corazón del narcotráfico”. https://es.aleteia.org/2019/09/15/peru-cruzada-contra-la-hoja-de-coca-en-vraem-corazon-del-narcotrafico/ Access 08.03.2024

APNews. (2024). “México pide a EEUU investigar cómo armas de uso exclusivo de su ejército caen en manos de cárteles”. https://apnews.com/world-news/general-news-f683216bda444afadadfcd56203f63a8 Access 08.03.2024

Arroyo, M. B. (2023). “¿Cómo se infiltró la mafia albanesa en Ecuador sin ser vista?: https://www.vistazo.com/actualidad/como-se-infiltro-la-mafia-albanesa-en-ecuador-sin-ser-vista-KN4593738 Access 07.02.2024

Avelar, B. (2023). “La embestida de Bukele contra las maras suma más de 170 muertes en El Salvador”. https://elpais.com/internacional/2023-01-31/la-embestida-de-bukele-contra-las-maras-suma-mas-de-170-muertes-en-el-salvador.html Access 08.03.2024

Badillo, D. (2023). “Registran hasta 400 células de tráfico de migrantes”. https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/Traficantes-de-migrantes-una-especie-de-alacranes-a-la-que-le-salieron-alas-20231006-0085.html Access 14.04.2024

Basantes, A. C. (2024). “Daniel Novoa declara un conflicto armado interno en Ecuador”. https://elpais.com/america/2024-01-09/daniel-noboa-declara-un-conflicto-armado-interno-en-ecuador-tras-la-irrupcion-en-directo-de-un-comando-armado-en-un-canal-de-television.html Access 05.03.2024

BBC. (2016). “Video de Panama Papers” https://www.bbc.com/mundo/video_fotos/2016/04/160404_video_panama_papers_investigacion_cof Access 05.03.2024

BBC. (2023). “Asesinato de Fernando Villavicencio: cómo pasó Ecuador de ser país de tránsito a un centro de distribución de la droga en América Latina”. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-66469463 Access 02.03.2024

BBC. (2024). “3 claves que explican el “conflicto armado interno” declarado en Ecuador tras varias jornadas de violencia” https://www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/cerlp2w1rrpo Access 05.03.2024

Becker, D. C. (2011). “Gangs, Netwar, and Community Counterinsurgency in Haiti”. JSTOR, 18.

Berlinguer, J. (2016). “4 razones por las que Panamá se utiliza como paraíso fiscal”. https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2016/04/07/papeles-de-panama-4-razones-por-las-que-panama-se-utiliza-como-paraiso-fiscal/ Access 18.02.2024

Bugari, I. (2010). “ Holanda 34 años de tolerancia de drogas”.

https://www.bbc.com/mundo/cultura_sociedad/2010/07/100701_holanda_aniversario_marihuana_jrg Access 18.04.2024

Buitrago, R. (2022). “La perspectiva de formación política y militar de las FARC-EP como movimiento insurgente”. Revista Espacio Sociológico E-ISSN: 2805-7007, 27.

Cano, J. (2023). “Ruta del fentanilo en México: así se transporta el opioide sintético con destino a EEUU”.

https://www.infobae.com/mexico/2023/11/20/ruta-del-fentanilo-en-mexico-asi-se-transporta-el-opioide-sintetico-con-destino-a-eeuu/ Access 16.03.2024

Cañas, J. (2024). “Ocho detenidos por la muerte de dos guardias civiles embestidos por una narcolancha en Cádiz” https://elpais.com/espana/2024-02-09/dos-guardias-civiles-mueren-tras-embestir-contra-ellos-una-narcolancha-en-cadiz.html. Access 16.03.2024

CasaAfrica. (2024). “GAR-SI Sahel”

https://www.casafrica.es/es/redes/gar-si-sahel Access 16.03.2024

Chaparro, J. (2019). Operación dockers” https://www.europasur.es/algeciras/Policia-trafico-cocaina-portuarios-operacion-dockers_0_1403259895.html Access 16.03.2024

Clarkson, W. (2010). “Gang Wars on the Costa - The True Story of the Bloody Conflict Raging in Paradise”. Kings Road Publishing, 2010.

Clemente Castrejón, R. (2022). “La guardia civil en la lucha contra el narcotráfico. Operación Carteia". Armas y Cuerpos, ISSN-e 2445-0359, Nº. 149. 2022. pp. 69-74.

El Correo. (2023). “Así es la gran cárcel que el presidente Nayib Bukele ha inaugurado en El Salvador. https://www.elcorreo.com/internacional/gran-carcel-presidente-nayib-bukele-inaugurado-salvador-20230228193012-virc.html Access 16.03.2024

Cueva López, A. (2015). “Sendero Luminoso en el VRAEM”. https://www.esffaa.edu.pe/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/LIBRO-SENDERO-LUMINOSO-EN-EL-VRAEM.pdf Access 16.03.2024

Dammert, L. (2023). “El «modelo Bukele» y los desafíos latinoamericanos”. Revista Nueva Sociedad No 308, 15.

Darren, T. (2021). “Por qué los puertos africanos son un coladero para las vacunas anti-covid falsificadas”.

https://elpais.com/planeta-futuro/2021-04-07/por-que-los-puertos-africanos-son-un-coladero-para-las-vacunas-anti-covid-falsificadas.html Access 16.02.2024

Del Moral Torres, A. (2016). “Cooperación Internacional de interés policial”. Aranjuez: CUGC.

Delgado, A. and Lares, V. (2022). “El Cartel de Los Soles: herederos de Chávez que convirtieron a Venezuela en bastión del narcotráfico” https://www.elnuevoherald.com/noticias/america-latina/venezuela-es/article281390553.html Access 16.03.2024

DW. (2022). Video “Why can't Sweden get gang violence under control?

Focus on Europe. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwWMjxLrmVE

Access 22.03.2024

Efeverde. (2023). “Mineria ilegal en la amazonia brasileña” https://efeverde.com/mineria-ilegal-amazonia-brasilena/ Access 22.03.2024

Ejecentral. (2023). “Reconoce Joe Biden que EU envía armas de ‘guerra’ a México”. https://www.ejecentral.com.mx/reconoce-joe-biden-que-eu-envia-armas-de-guerra-a-mexico Access 21.03.2024

Ejecentral. (2024). “Ecuador copia modelo de Bukele” https://www.ejecentral.com.mx/ecuador-copia-modelo-de-carceles-de-bukele-en-el-salvador Access 22.03.2024

Erhardt, E. (2023). “El hachís en Marruecos”. https://softsecrets.com/es-ES/articulo/el-hachis-en-marruecos#:~:text=Las%20cifras%20oficiales%20ofrecidas%20por,hect%C3%A1reas%20al%20cultivo%20de%20Cannabis. Access 22.02.2024

ERIC-Group. (2001). “Maras y pandillas en Centroamérica: Políticas juveniles y rehabilitación”. UCA Publicaciones.

Esglobal. (2016). ¿Están de vuelta los piratas en el golfo de Adén? https://www.esglobal.org/estan-vuelta-los-piratas-golfo-aden/ Access 12.03.2024

Espectador. (2021). “Así fue la Operación Agamenón que logró dar con el paradero de alias Otoniel” https://www.elespectador.com/judicial/asi-fue-la-operacion-agamenon-que-logro-dar-con-el-paradero-de-alias-otoniel/ Access 10.03.2024

EURLEX. (2001). Council Common Position 2001/931 of 27 December 2001 on the application of specific measures to combat terrorism.

EUROPAPRESS. (2020). “Más de 70 personas detenidas o investigadas por tráfico ilegal de maderas protegidas desde Brasil y África central” https://www.europapress.es/sociedad/medio-ambiente-00647/noticia-mas-70-personas-detenidas-investigadas-trafico-ilegal-maderas-protegidas-brasil-africa-central-20200228085958.html Access 22.02.2024

EUROPASUR. (2024). “Ocho toneladas intervenidas. Algeciras ruta mundial narcotráfico” https://www.europasur.es/algeciras/ocho-toneladas-intervenidas-cocaina-ruta-mundial-narcotrafico_0_1875113122.html Access 22.03.2024

EUROPOL. (2023). Serious Organized Crime Assessment (SOCTA). Retrieved from https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/main-reports/socta-report Access 20.02.2024

Ferri, P. (2024). “La reforma de la Guardia Nacional: control total para la Secretaría de la Defensa y facultades de investigación” https://elpais.com/mexico/2024-02-06/la-reforma-de-la-guardia-nacional-control-total-para-la-secretaria-de-la-defensa-y-facultades-de-investigacion.html Access 15.04.2024

Flores, E. (2022). “El tráfico de armas que llega a Michoacan pasa por Jalisco, Guajanato y Colima” https://www.debate.com.mx/estados/El-trafico-de-armas-que-llega-a-Michoacan-pasa-por-Jalisco-Guanajuato-y-Colima-20220704-0137.html Access 15.04.2024

García Bravo, A, De Hoyos, K, and Fernández Ramírez, Oscar Eduardo. (2018). “Erradicación cultivos ilícitos: una mirada socialmente responsable”. ADGNOSIS, 8.

González Díaz, M. (2023). “Ovidio Guzmán: la ola de violencia que asoló Culiacán tras la detención del hijo del Chapo” https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-64181926 Access 11.04.2024

GOV.CO. (2023). “La estrategia de erradicación de cultivos ilícitos ha sido fallida: MinJusticia”. https://www.minjusticia.gov.co/Sala-de-prensa/Paginas/Minjusticia-laestrategia-de-erradicacion-de-cultivos-ilicitos-ha-sido-fallida-.aspx Access 15.04.2024

Guevara, T. (2021). ¿Es el estrecho corredor de Centroamérica la autopista de las drogas hacia EE. UU.? https://www.vozdeamerica.com/a/centroamerica_centroamerica-triangulo-norte-drogas-hacia-eeuu/6074903.html Access 10.03.2024

GVA. (2024). Gun Violence Archive. https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/ Access 10.03.2024

Hernández, A. (2019). “Holanda, gran productor mundial de drogas sintéticas” https://www.dw.com/es/holanda-uno-de-los-principales-productores-de-drogas-sint%C3%A9ticas-del-mundo/a-51442620 Access 10.03.2024

Hidalgo, C. (2024). "ABC. Retrieved from La superproducción de coca, más barata multiplica los narcopisos en Madrid https://www.abc.es/espana/madrid/superproduccion-coca-barata-multiplica-narcopisos-madrid-20240223042426-nt.html Access 10.03.2024

InSightCrime. (2017). “Mayor caso de corrupción policial ‘de la historia’ se descubre en Rio de Janeiro, Brasil” https://insightcrime.org/es/noticias/noticias-del-dia/mayor-caso-corrupcion-policial-historia-descubre-rio-de-janeiro-brasil/ Access 10.03.2024

Insightcrime. (2023). “Tren de Aragua” https://insightcrime.org/es/noticias-crimen-organizado-venezuela/tren-de-aragua/ Access 12.04.2024

Jímenez Vigara, M. (2019). “Sendero Rojo o el Partido Comunista del Perú Marxista-Leninista-Maoísta (1992-1999) Ideología, Organización y Estrategia”. Americanía: Revista de Estudios Latinoamericanos.

Kabbaj, M. (2024). Maroc Hebdo. El HAdj Admed Ben Brahim, le Pablo Escobar du Sahara. https://www.maroc-hebdo.press.ma/elhadj-ahmed-ben-brahim-pablo-escobar-sahara Access 12.04.2024

Lucena, P. (2023). “Punta del Este: un centro importante para operaciones del lavado, según especialista internacional en narcotráfico” https://www.m24.com.uy/punta-del-este-un-centro-importante-para-operaciones-del-lavado-segun-especialista-internacional-en-narcotrafico/ Access 13.04.2024

Madrid Diario (2018). “Cae la organización más activa dedicada a la estafa con 'cartas nigerianas” https://www.madridiario.es/457327/cae-organizacion-activa-estafa-cartas-nigerianas Access 12.04.2024

Maesschalck, M. (2020). “Haití: del colapso del Estado al narco-caos". https://books.openedition.org/ariadnaediciones/6114?lang=es Access 20.04.2024

Marley, D. F. (2019). "Mexican Cartels: An Encyclopedia of Mexico's Crime and Drug Wars". ABC-CLIO.

Martínez, M. (2017). “Mercado de esclavos en Libia”: https://www.elperiodico.com/es/internacional/20170411/mercado-esclavos-libia-5967609 Access 20.04.2024

Mella, C. (2023). “La inseguridad en Ecuador escala a niveles históricos y se impone como prioridad del próximo Gobierno”. https://elpais.com/internacional/2023-07-10/la-inseguridad-en-ecuador-escala-a-niveles-historicos-y-se-impone-como-prioridad-del-proximo-gobierno.html Access 21.03.2024

Méndez, V. (2018). "Narcogallegos: Tras los pasos de Sito Miñanco”. Los Libros De La Catarata.

Meneses, P. (2008). “Cada mes, minas acaban con la vida de un erradicador de coca. https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/MAM-3063449 Access 22.04.2024

Montalvo, T. (2016). “Enviar armas por pieza de EU a México, la nueva (y legal) forma de tráfico”. https://animalpolitico.com/2016/01/pieza-por-pieza-la-nueva-manera-de-traficar-armas-de-estados-unidos-a-mexico-2 Access 19.04.2024

Montaño, F. (2022). “Mejoras genéticas en cultivos de hoja de coca aumentan la producción mundial de cocaína” https://ojo-publico.com/sala-del-poder/crimen-organizado/mejoras-geneticas-la-hoja-coca-aumentan-la-produccion-cocaina Access 22.04.2024

Moreno Segura, L. (2023). “La Comuna 13 de Medellín se abre a los turistas” https://elpais.com/planeta-futuro/seres-urbanos/2023-03-07/la-comuna-13-de-medellin-se-abre-a-los-turistas.html Access 22.04.2024

Ojopúblico. (2023). Triple frontera: mafias de Brasil toman control de producción de coca. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lu1f0-n1wJw Access 21.03.2024

ONU. (2000). Convención de las Naciones Unidas contra la delincuencia organizada transnacional. ONU. 2000.

ONU. (2023). Estudio Global sobre Homicidios de la ONU: https://www.swissinfo.ch/spa/la-tasa-de-homicidios-de-los-pa%C3%ADses-de-am%C3%A9rica-latina-y-caribe/49042834 Access 10.02.2024

Ordaz, P. (2018). “Spain: Europe’s new cocaine gateway”. https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/07/02/inenglish/1530521093_187450.html Access 22.04.2024

Observatorio del Crimen Organizado de Ecuador (2022). “Evaluación situacional del narcotráfico Ecuador 2019-2022”.

https://oeco.padf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/EVALUACION-SITUACIONAL-NARCOTRAFICO-ECU-2019-2022-.pdf Access 09.03.2024

Ortega Doltz, P. (2015). “Spanish police crack down on Gibraltar cigarette smugglers”. https://elpais.com/elpais/2015/03/26/inenglish/1427360372_935685.html Access 12.03.2024

Ortega Dolz, P. (2019). “Apresado en Galicia el primer ‘narcosubmarino’ de Europa con más de 3.000 kilos de cocaína” https://elpais.com/politica/2019/11/24/actualidad/1574598267_187838.html Access 09.04.2024

Palomino, C. (2023). “Marruecos, la potencia mundial del hachís que no quiere renunciar al negocio”. https://elordenmundial.com/marruecos-hachis-cannabis-potencia/ Access 12.03.2024

Parker, A. and Dudley. S. (2023). “Trata de personas en la frontera México-Estados Unidos: ¿clanes familiares, coyotes o ‘carteles’?” https://insightcrime.org/es/investigaciones/clanes-coyotes-carteles-trata-frontera-estados-unidos-mexico/ Access 12.03.2024

Pasquali, M. (March 2023). “Los países que producen la mayor cantidad de cocaina” https://es.statista.com/grafico/20081/los-paises-que-producen-la-mayor-cantidad-de-cocaina/ Access 25.04.2024

Passolas, F. (2018). “Los narcos de Algeciras cada vez se parecen más a los de Colombia y México” https://www.vice.com/es/article/ev8qvz/narcos-algeciras-institucionalizacion-violencia-politica-drogas Access 12.03.2024

Prado, J. C. (2016). “Crimen organizado: una aproximación a la frontera boliviano-argentina” https://nuso.org/articulo/crimen-organizado-una-aproximacion-la-frontera-boliviano-argentina/ Access 22.04.2024

Quesada, J. D. (2023). “El ELN se atribuye un atentado con tres muertos mientras sigue estancando el alto el fuego” https://elpais.com/america-colombia/2023-05-26/el-eln-se-atribuye-un-atentado-con-tres-muertos-mientras-sigue-estancando-el-alto-el-fuego.html Access 10.03.2024

Quirós, L. (2019). “La expansión del Primeiro Comando da Capital en la frontera amazónica por lograr la hegemonía de las rutas de la droga” http://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/wps/portal/rielcano_es/contenido?WCM_GLOBAL_CONTEXT=/elcano/elcano_es/zonas_es/ari27-2019-quiros-expansion-primeiro-comando-da-capital-frontera-amazonica-hegemonia-rutas-droga Access 12.03.2024

Rognoni, M. (2024). “Obtenido de Panamá y el lavado de dinero” https://prensaeconomica.com.ar/2017/03/panama-y-el-lavado-de-dinero/ Access 12.03.2024

RTVE. (2023). “Mocro Maffia, la nueva mafia de la droga que opera en el corazón de Europa” https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20230531/mocro-mafia-organizacion-criminal-opera-corazon-europa/2435787.shtml Access 22.03.2024

Sánchez Moreno, e. (2021). “Minerales en conflicto: la guerra del coltán en la República Democrática del Congo”. Universidad Pompeu Fabra. Retrieved from https://www.tecnologialibredeconflicto.org/minerales-congo/ Access 21.04.2024

Sánchez Oliveria, L. (2023). “Estafa Nigeriana” https://nordvpn.com/es/blog/estafa-nigeriana/ Access 21.04.2024

Sanhueza, A. M. (2023). “El Tren de Aragua: cómo la banda se instaló en Chile y las operaciones para desarticularla una y otra vez”. https://elpais.com/chile/2023-09-24/el-tren-de-aragua-como-la-banda-se-instalo-en-chile-y-las-operaciones-para-desarticularla-una-y-otra-vez.html Access 21.04.2024

Serrano, C. (2024). “Estos son los delincuentes más peligrosos del Estrecho” https://www.larazon.es/espana/estos-son-narcotraficantes-mas-peligrosos-estrecho_2024021565cdea07344c980001a1af6e.html Access 24.05.2024

Stroobants, J.-P. (2022). “Dutch crown princess and prime minister threatened by drug mafia”. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2022/10/15/dutch-crown-princess-and-prime-minister-threatened-by-drug-mafia_6000465_4.html Access 24.05.2024

Tomlinson, C. (2023). Sweden’s Crime Rate Now Highest in Northern Europe. https://europeanconservative.com/articles/news/swedens-crime-rate-now-highest-in-northern-europe/ Access 21.05.2024

Torrado, S. (2022). “Colombia sepulta las fumigaciones aéreas con glifosato”. https://elpais.com/america-colombia/2022-11-17/colombia-sepulta-las-fumigaciones-con-glifosato.html Access 21.05.2024

UNODC. (2004). “Guía legislativa de las Convenciones de las Naciones Unidas contra el terrorismo” https://www.unodc.org/pdf/Legislative%20Guide%20Mike%2006-56983_S_Ebook.pdf Access 21.01.2024

UNODC. (2021). Colombia: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos. https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/INFORME_MONITOREO_COL_2021.pdf Access 12.02.2024

UNODC. (2022). Colombia: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos. https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Colombia_Monitoreo_2022.pdf Access 12.02.2024

UNODC. (2022). “El cultivo de coca alcanzó niveles históricos en Colombia” https://www.unodc.org/colombia/es/el-cultivo-de-coca-alcanzo-niveles-historicos-en-colombia-con-204-000-hectareas-registradas-en-2021.html Access 11.01.2024

UNODC. (2023). “Firarms trafficking in the Sahel” https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tocta_sahel/TOCTA_Sahel_firearms_2023.pdf Access 12.02.2024

UNODC. (2023). “Colombia desacelera la siembra de coca: tras un aumento del 43 % en 2021, en 2022 fue del 13 %”. https://www.unodc.org/colombia/es/informe-de-monitoreo-de-territorios-con-presencia-de-cultivos-de-coca-2022.html#:~:text=Bogot%C3%A1%20D.C.%2C%2011%20de%20septiembre,a%20230.000%20ha%20en%202022

UnoTV. (2020). ¿A qué se le conoce en México como “culiacanazo” o “jueves negro”? https://www.unotv.com/nacional/ovidio-guzman-que-es-el-culiacanazo-o-jueves-negro/ Access 22.03.2024

Velázquez, J. (2013). ABC. “Las maras sudafricanas se apoderan del extrarradio de Ciudad del Cabo” https://www.abc.es/internacional/20130919/abci-maras-sudafricanas-ciudad-cabo-201309181057.html Access 10.05.2024

Voss, G. (2024). “Exprimer ministro de las Islas Vírgenes Británicas culpable de caso de narcotráfico” https://insightcrime.org/es/noticias/exprimer-ministro-islas-virgenes-britanicas-culpable-caso-narcotrafico/ Access 10.05.2024

Vozpópuli. (2024). “Nayib Bukele arrasa en las elecciones de El Salvador con más del 80% de los votos”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s7HCFdpB6TQ Access 22.05.2024

Wright, A. (2013). “Organised Crime”. Routledge.

Zupello, M. (2023). “Brasil es la nieva ruta principal del narcotráfico que llega a Europa a través de África” https://www.infobae.com/america/america-latina/2023/09/25/brasil-es-la-nueva-ruta-principal-del-narcotrafico-que-llega-a-europa-a-traves-de-africa/ Access 22.05.2024