María Dolores de la Cruz Fresneda

Health and Legal Psychologist

Master's Degree in Legal Psychology

and Forensic Psychological Expertise

Master's Degree in Strategic Consulting

LEADERSHIP IN EMERGENCY AND CRISIS SITUATIONS.

INFLUENCE OF THE PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTOR AND THE ROLE OF LEADERS

LEADERSHIP IN EMERGENCY AND CRISIS SITUATIONS.THE INFLUENCE OF THE PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTOR AND THE ROLE OF LEADERS.

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE PHENOMENON OF LEADERSHIP. 2.1. Theoretical approaches to the leadership process. 2.1.2 Influence of informal groups on the leadership process. 2.2. Leadership challenges 3. EMERGENCY SITUATIONS. A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS. 3.1 Concept. Definition and types 3.2. The importance of context. VUCA and BANI models. 4. THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS UNDER STRESS. THE INFLUENCE OF EMOTIONS AND THE PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTOR. 4.1. The role of emotions in decision-making. 4.2. The decision-making process in emergency and crisis situations. 4.2.1. Uncertainty and risk assessment 4.2.2 The panic phenomenon 5. THE IMPORTANCE OF LEADERSHIP AND LEADERS IN CRISIS AND EMERGENCY SITUATIONS. 6. LEADERSHIP IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS. APPLICABILITY TO THE GUARDIA CIVIL. 7. CONCLUSIONS BIBLIOGRAPHY.

Abstract: Leadership is a complex and broad phenomenon that structures groups, organisations and societies. Leadership, the role of leaders and the decision-making process becomes especially relevant when we are faced with an emergency or crisis situation. One of the most notable issues in this regard is the influence of the psychological factor and emotional impact, as well as the management of the uncertainty and risk that this type of context entails, in decision-making and team leadership. In this text, we aim to analyse these issues and their application in the emergency and law enforcement agencies, with a special focus on the Guardia Civil. Due to its nature and the work it performs, we consider leadership in emergency and crisis situations to be a significant and far-reaching topic.

Resumen: El liderazgo es un fenómeno complejo y amplio, que vertebra los grupos, las organizaciones y las sociedades. El liderazgo, el papel de los líderes y el proceso de toma de decisiones, adquiere especial relevancia, cuando nos encontramos ante una situación de emergencia o crisis. Una de las cuestiones más destacadas en este sentido, es la influencia del factor psicológico y el impacto emocional, así como la gestión de la incertidumbre y el riesgo que conllevan este tipo de contextos, en la toma de decisiones y en el liderazgo de los equipos. En el presente texto, tratamos de analizar estas cuestiones, y su aplicación en los equipos de emergencias y FCSE, haciendo un especial matiz en el cuerpo de la Guardia Civil, dado que, por su naturaleza, así como la labor que desempeña, el liderazgo en situaciones de emergencia y crisis, consideramos que es una temática significativa y de alcance.

Keywords: Leadership, teams, emergencies, decision-making process, emotional impact, challenge.

Palabras clave: Liderazgo, equipos, emergencias, proceso toma de decisiones, impacto emocional, desafío.

1. INTRODUCTION

In this text, we will try to go deeper into the process of leadership in emergency and crisis situations. The literature and research on this phenomenon is mainly focused on areas such as healthcare, but it is also present in many others, and especially in the State Security Forces and Corps (FCSE), due to the nature of their work.

To do so, we will begin by reviewing the phenomenon of leadership, decision-making processes and emergency or crisis situations of different kinds, concluding this analysis and its application in the field of the FCSE.

The FCSE, such as the Guardia Civil, is a type of organisation that has particular characteristics, as do the professionals who work for them, due to the type of institution, the work carried out, the functions derived from it, and the tasks or challenges they face. For this reason, and because of the type of organisation we are dealing with, we consider this analysis to be of interest, as we will address the process of leadership in emergency and crisis situations.

Therefore, all this leads us to try to analyse this process of leadership in critical situations, and to provide a view on the above, with a particular focus on the FCSE. This subject is being applied to this type of organisation due to the fact that one of the FCSE’s main tasks within the public service it performs is to deal with emergency or critical situations. There are other teams or organisations whose main tasks include or focus on dealing with such situations, like fire brigades, health teams, teams prepared for emergencies in civil organisations, such as NGOs, to name but a few.

For all these reasons, we will review the leadership process, with special emphasis on these emergency, critical and/or crisis situations. We will refer to these situations during our analysis, as we consider leadership and the decision-making process itself to be necessary and useful for all organisations of different types and objectives, as well as for professionals who deal with this type of highly uncertain situations. This includes managing the emotional impact of these situations, which is crucial for developing a team and realising the work to be carried out.

2. THE PHENOMENON OF LEADERSHIP.

Leadership is one of the most studied concepts, both as a phenomenon and as a process, due to the implications it has at the individual, group, institutional and social levels. Leadership is a complex phenomenon that has evolved over time. Thus, the study of leadership, its conceptualisation, the definition of “leader” and the development of leadership training materials has generated a large and sometimes ambiguous body of knowledge.

Current trends point towards the study of leadership and leaders in a systemic and comprehensive way, in line with the interests of the society that defines it and the trends of the moment.

We begin with a theoretical overview of leadership to lay the groundwork for the topic at hand, namely leadership in crisis and emergency situations.

2.1. CONCEPT AND OBJECTIVES.

Firstly, we will delve into the theory about the phenomenon of leadership. Blanco, Caballero and De La Corte (2005) indicate that “the central characteristic of leadership is the capacity to exert influence over a group of people [...] Through the process of leadership, changes are achieved in the attitudes and behaviours of followers, and even changes in their beliefs can be induced”. Thus, in order to be able to speak of a leadership process or leaders, there must be a group of people who are influenced or become influenced by the leaders. (Blanco, Caballero and De La Corte, 2005).

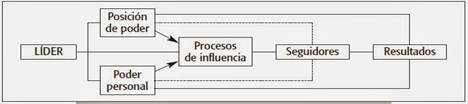

In this sense, we find that when we speak of leadership, we talk about two processes implemented by leaders. On the one hand, there is holding a position of power and, on the other, the possibility of exerting influence (Blanco, Caballero, De La Corte, 2005). The following table summarises the leadership process in graphic form.

|

Figure 1. Jesuino's leadership model (1996). Taken from Blanco, Caballero and De La Corte (2005). |

This graph shows the leadership process, based on the assumption that leaders have a position of power with respect to the other members of the group, exert influence on them, pursue the achievement of the objectives set and the effectiveness of their group in achieving these.

This social power is based on the various types of power described by the authors Blanco, Caballero and De La Corte (2005), which are described below:

- The power of reward. This is power whose basis is the ability to grant benefits, rewards and accolades to a person. It is the power attributed to those who influence others, because they have the ability to reward them for their actions. For example, salary compensation or employee congratulations, among other rewards.

- Coercive power. This is based on the possibility of penalising behaviour that is considered inappropriate, does not conform to group norms or is considered contrary to them. In general, it is based on a reluctance to be penalised.

- Referent power. With referent power, influence is manifested through leaders’ personal aspects, based on personality, identification with others, the values they represent or the prestige they are recognised for. In this case, leaders act as a reference point for the group and give group members’ identity. Most leaders of informal groups, such as groups of friends, emerge from this kind of power.

- Legitimate power. This is based on position, and represents “formal” power, which group members accept according to a structure (military, academic, organisational hierarchy) or procedure that is shared according to context, e.g. majority choice.

- Expert power. This is power given to those we consider to have the most experience or judgement to resolve certain issues. It is power based on the trust we place in people due to their competencies, skills and knowledge.

- The power of information. This is based on possession of or access to data or information, which places the person or group in a position of privilege.

- The power of connection. This refers to the power that arises from the relationship with “influential” people, with whom one wants to be associated for some purpose.

Following this analysis of the types of power that can contribute to the social power granted to leaders, we will continue by analysing the process of leadership and its other component, which we pointed out earlier: influence.

In the leadership process, as reflected in Figure 1, synergies occur between followers and leaders. However, leaders are considered to have greater capacity to influence their followers than they themselves can be influenced, even if there are synergies in both directions, leaders-followers, followers-leaders.

For this to happen, it is necessary to have some decisive components, an adequate planning strategy, supervision, evaluation of the development of the task and achievement of the objectives, and continuous improvement processes, in accordance with the objectives that are set. However, if there is a lack of optimal and effective leaders for this, who provide direction, it is difficult for the organisation to be maintained over time (Noriega, 2008).

The importance of leaders and their role in groups, organisations and, ultimately, the society in which they operate, stems from the fact that they are the driving force behind these entities, but they also generate added value for them, with which they are both identified.

Figure 2. Identification synergy. Source: Prepared internally

Therefore, and as mentioned above, we can consider leaders to be key people in the group, team or organisation, and therefore the axis of the group, team or organisation. In addition, they are the most visible or best known members outside that entity, as well as advocates of the entity's interests vis-à-vis other groups. (Blanco, Caballero, De La Corte, 2005)

Leaders are known to be omnipresent, i.e. regardless of whether they are physically present, and they do not need to constantly give instructions, as they are recognised and taken into account by all members of the group, as well as their indications or objectives. Similarly, leaders are extremely knowledgeable about the group and its members, and also about the functioning of the group, its strengths and needs.

Leaders are expected to act when the situation requires it, mainly by making decisions or giving direction, so that the group, team or organisation follows the direction or objectives set, even when the leader does not intervene directly, as mentioned above. All of this starts from the main foundation that leaders have the necessary skills and knowledge to ensure that the team achieves its objectives, as well as the capacity to influence parties both inside and outside the group.

Accordingly, making decisions, setting goals or objectives and assigning tasks is carried out from the privileged position leaders hold within the group, the team or the organisation, taking into account the influence and status that the group itself grants to the leaders for this purpose. In other words, leaders are given this specific and differential role, based on a series of qualities and capacities, strategic vision and know-how, recognised by the other members of the group or the followers, always in line with the organisation's objectives, with which they identify.

This vision must be realistic and shared with the members of the group, as well as ensuring the commitment and participation of the members, in order to achieve the objectives set. Without these characteristics, it is difficult for the members of the group to identify with the aims and with the group itself and, therefore, for the process of influence and guidance that we have been talking about to take place.

In addition to this vision, we must take into account another issue that is no less important, which is for leaders to be immersed in a process of constant evaluation and improvement, both by the members of their own group and by groups outside their own.

In other words, leaders are constantly evaluated on their delivery, performance and achievement of objectives, as well as on the effectiveness of their group in achieving the goals set. If the group considers that the leader is not exercising this role correctly, or is not achieving the objectives that are set or assumed, and no plausible explanation is found to support this non-achievement of objectives, especially if it is repeated, or if there is no maintenance or improvement of those already achieved, the role of authority granted to the leaders dissipates and a process of replacement or substitution and reorganisation of the same would be considered.

Reorganisation processes are complex and informal groups are particularly relevant, as we will see below. The following is an overview of theoretical approaches to leadership.

2.1 THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO THE LEADERSHIP PROCESS

The phenomenon of leadership is complex and wide-ranging. We will delve into the theory of leadership, starting from three main theoretical approaches throughout history (Blanco, Caballero and De La Corte, 2005):

- Trait approach: leadership as a result of a set of personality traits and characteristics (Great Man Model).

- Behavioural approach: approaches leadership as behaviours more oriented towards task effectiveness or towards group relationships and people. Examples are the Ohio State University Leadership Studies or Blake and Mouton's Leadership Grid model.

- Situational approach: considers the leadership process as the synergies of traits and behaviours in a given context or situation, with the ability of these traits and behaviours of leaders to adapt to situations. Examples are Fielder's Leadership Effectiveness model, or Hersey and Blanchard's Situational Leadership theory.

Currently, the approach used is the one proposed by Bass in 1985, in which two types of leadership are indicated, which we will discuss below. However, this approach gives greater importance to transformational leadership, as it is considered more socially appropriate (Rozo and Abaunza, 2010).

- Transactional leadership. We are talking about a type of leadership based on more traditional models. It is based on exchange or transaction, i.e. the leadership relationship involves an exchange between followers and leaders. Leaders who can be considered transactional base their leadership on support, motivation, contingent reward, sanction or administration by exception, i.e., they intervene when it is necessary to correct an issue, the group or its members, to the extent that the group's objectives are achieved or contributed to, depending on their performance or fulfilment of tasks. It is a type of leadership that concentrates more on performing tasks and achieving objectives.

- Transformational leadership is more focused on leaders as agents of change, who promote commitment and motivate the team; they take into account qualities, seek to build relationships based on trust, commitment, cooperation and activities with shared meaning. It is a type of leadership that takes into account the values, beliefs and personal qualities of both leaders and followers, in which social and personal skills are developed, increasing the self-esteem of both leaders and followers, thus leading to better results, as well as satisfaction and benefits for them and the organisation (Varela, 2010).

It considers team members on a more individual level as a person, rather than as a tool to achieve objectives, which fosters the integration of the team member into the team, identification with the team and greater commitment of the team member to the task, objectives, team and leaders. Transformational leaders stimulate and motivate followers, also intellectually, by taking their ideas into account, consulting them or involving them in the decision-making process and, especially, in the results obtained. This type of event strengthens relationships of trust, cooperation and respect, and ensures that the team remains cohesive and continues to share values, ideas and objectives, with added value and meaning. In addition to this, their autonomy, innovation and creativity are encouraged, as well as individual and group motivation, all of which is necessary and beneficial both for being assigned tasks and for the group, the organisation or the ultimate beneficiary of objectives being achieved, which sometimes benefits the society in which it operates, as is the case, for example, with the FCSE.

Followers have a personal regard for leaders. We could say that they see them as role models, sharing ideas or ways of thinking, which facilitates identification with them, as well as motivation and cohesion among the group’s members. In addition to this, they generate concerns or intellectual curiosity among their followers, which favours this influence, either because they identify with or are close to their interests, or because they already had this concern, and become attached to the group.

An important point to highlight in leadership is the possibility of situations in which the task is achieved by the team or group thanks to loyalty and commitment to the leaders. Tasks also achieved through consideration, appreciation and identification with leaders, since they are considered to be role models. The cohesion of the team, rather than the organisation itself or other motivations if the team belongs to a larger entity or organisation, is also instrumental in this.

Also fundamental for leadership is the projection of the leaders' image. In order to maintain this role and continue to be a person that members of the group look up to, leaders’ technical capacity and ability to build social relationships is key. This not only involves intra-group relations, based on trust, honesty and mutual respect between leaders and followers, but also inter-group relations, representation, negotiation and defence, i.e. setting limits with other groups, if necessary.

In relation to the leadership process, it is important to highlight that the effectiveness of leadership is a matter of style and the ability of leaders to adapt their style according to the nature of the task and objective, as well as to the team members and potential team members, the context, means and resources. By doing so, they can guide the group in an adequate way for effective performance of the task to be carried out.

To conclude, it is important to bear in mind some concepts, such as the importance of followers and the context in which leadership is exercised, the relevance of leaders’ power and influence with respect to group members and their perception of how effective leaders are, in order to continue reinforcing this link and role within the group. If not, the leader will lose this appreciation, even if they do not lose their position of leadership, which hinders group development and prevents tasks from being completed. In the case of formal organisations, under these circumstance, informal groups may develop within formal ones. We will examine a case in point below.

2.1.2 Influence of informal groups on the leadership process.

Here we will discuss the influence of informal groups on the organisation and its development, as well as on the performance of the group or organisation. We start from the premise that “people associate, collaborate and interact for the achievement of their goals and the achievements of the organisation” (Cequea and Rodríguez, 2012).

There are also social dynamics within organisations. Individuals tend to group together, as “team members are not simply individuals, but members of a certain group, within which their rules of mutual relations are formed” (Hernández, 1995; Aktouf, 2001; Cruz, Aktouf and Carvajal, 2003; Hodge, Anthony and Gales, 2003; Murillo et al., 2007).

When we talk about the organisational level, there are two types of groups. On the one hand, we start from the groups formed on the basis of carrying out a task and organisational objectives set by the organisation, its structure, its members, hierarchical ranks and the task to be carried out. We could say that this comprises the organic structure of the work teams. On the other hand, we also have the informal groups. These informal groups originate from the organisation, as their components are derived from work teams, but their development is often parallel to the formal group. They originate around interactions, shared interests and emotions, and friendships may be formed (Robbins and Coulter, 2010).

This influence of informal groups is marked by the state of the groups, i.e. if there is a high degree of cohesion, collaboration, commitment and sense of belonging, no major conflicts arise, or if these disagreements are able to be resolved, they have a favourable influence on the individuals who form part of the group. As a result, they support the performance of their members and the group itself, both in terms of achieving objectives and group performance.

Otherwise, informal groups would become a source of inconvenience rather than a system that supports organisational goals. If any disagreements that may arise are not resolved, they will affect the rest of the formal group, and may even have repercussions on the performance of the working team.

The emergence of informal groups within formal groups or organisations is inevitable. The alignment of the group becomes evident when the behaviour of the informal group starts to have an impact on the performance or development of the formal group, work team, or the organisation as such. From this point of view, there can be a positive, collaborative and supportive influence and impact that has a facilitating effect on the development of the formal group and the achievement of objectives.

However, negative influence may occur. In this sense, the informal group will hinder the functions and performance of the formal group, with possible consequences for both the group and, probably, the organisation. This support may even be lost at the individual level among group members or create different group identities, which could directly affect the working team and, in line with this, the team or group leaders.

The organisational climate and the dynamics of formal and informal groups are greatly influenced by communication and the communication process, as there are two possible scenarios in this respect. On the one hand, this has a facilitating role in which there is a positive impact that helps to streamline communication processes. On the other hand, there could be a negative aspect, leading to rumours and misunderstandings, and damaging the proper functioning of the organisation and the working environment. (Viloria, Daza and Pérez, 2016).

There is positive influence when the formal and informal group have the same perspective and feel identified with and integrated within the group and work towards achieving the same goals. However, it may happen that an informal group emerges, based on disagreements with the way of doing things, or due to the emergence of new leaders, who perhaps do not work contrary to the existing ones, but who put forward proposals that are more widely accepted. In this case, they would not work in the same direction, and situations of conflict may arise in the team dynamics and in the performance of the task, making it difficult to achieve, which would have repercussions for the organisational climate.

The functioning of the group, the figurehead and the role of leaders are closely related. Therefore, leaders must be attentive to these group dynamics, detect and try to resolve any difficulties that may arise in the group, whether these are formal or informal, if there is a possibility that they may affect the team, since as we can see, this can have repercussions at all levels for the rest of the group, and even the organisation.

If leaders remain inactive, do not know how the group works, do not detect its difficulties, and do not give direction or support to their team, they will not be perceived as decisive or competent in their functions, i.e. they will cease to be effective and will lose their role as leaders, and consequently, cease to be role models.

Under these circumstances, it is very possible that other leaders may emerge within the group who tend to become leaders on their own initiative or because the group dynamics give them that position. This would generate a conflict that, most probably, would call for a formal solution to give the group harmony again and restore its functions and development of tasks or duties in an effective way.

2.2. LEADERSHIP CHALLENGES.

In this review of the leadership process, it is also necessary to talk about the new challenges of leadership, since the objective of leadership is not only to perform its functions and what is expected of leaders in their position, but also involves other challenges.

Leadership must be strategic, i.e. it must set out a plan of action, integrating mission, vision and values, taking into account a perspective of the context, the team and its potentials, as well as the strategy or vision to set these objectives and lead the team over time.

The importance of values in the leadership process needs to be taken into account, as the values of the organisation and those of its members are often aligned. Organisational values frame the activity of the organisation and, therefore, those who form part of it, guiding their professional practice and decision-making on this basis. Leaders act as representatives and guardians of these values, and in turn project them to all stakeholders.

Leadership is also knowledge transfer, since, as we said, leaders are role models. From this role that the group gives them, leaders carry out their functions, but at the same time, there is an implicit or explicit act of teaching their team members, regardless of whether this is their primary objective, as would be the case of people whose main focus is teaching. This transfer of knowledge occurs in the sense that they are considered to be “masters”, as they have greater technical knowledge or experience in the task, which does not imply that there cannot be learning in reverse, i.e. from teams to leaders.

Leadership is transformational, as we could say that leaders are architects and agents of change, to the extent that they manage to carry their perspective forward with the support and conviction of team members, as well as the impact it generates for the audience or society in which they operate.

Leadership implies example, and as such exemplary behaviour, on the part of leaders. They lay the foundations for future leaders, as well as a shared vision, and a creation of meanings that influence each of the individuals that make up the group, both upwards and downwards in the organisation, as well as at a personal level, so that learning and teachings have an impact far beyond the mere fulfilment of objectives.

Leadership entails innovation, insofar as it brings about new challenges or proposes different alternatives to those already known at the time of resolving situations that arise, from a comprehensive point of view.

Leadership involves intermediation, understanding that the role of leader is also based on integrating all the alternatives, information or points of view and also the leader’s emotions in order to plan the activity, and in addition to this, intermediation requires negotiation capacity, both inside and outside the group.

Finally, we see a challenge for the leadership function itself in being able to give direction and meaning to the group's action in order to achieve effective goal attainment. This is a great challenge, given that new realities and contexts are being added that make it necessary to adapt to new situations in order to be able to give this direction.

Following this theoretical analysis of various aspects relating to leadership, we are now going to analyse the next point addressed by this text: emergency situations.

3. EMERGENCY SITUATIONS. A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS.

Emergency, critical or crisis situations can occur in any circumstance or context, whether individual, organisational or societal.

3.1 CONCEPT. DEFINITION AND TYPES.

Firstly, let us begin by defining what is meant by an emergency situation. According to the Spanish National Institute of Social Security (INSS), “an emergency is a situation or accident that occurs unexpectedly and may affect the physical integrity of people, property and/or the environment, either individually or collectively, and may sometimes constitute a situation of serious collective risk, catastrophe or public calamity”.(INSS, 2024).

It is important to highlight the unforeseen nature of emergencies, the probability and possibility of causing damage to people, facilities, processes and/or procedures, which in most cases merits immediate and priority action to prevent, mitigate or neutralise the consequences that could be caused. This rapid intervention requires a high level of preparation for this type of situation, both technical, mental and, in many cases, physical, as well as adequate management of stress and the emotional impact that may occur in these situations.

Mordechai Benyakar in his article, “Mental health and disasters. New challenges” indicates that emergency situations can be classified into two categories: those caused by an individual on the one hand, and those caused by nature on the other. (Benyakar, 2002)

With this classification in mind, let's take a closer look. Those provoked by an individual can be intentional, such as an individual or collective, physical or psychological aggression, in which the aggressor or aggressors are identified. However, it is also possible that the aggressor or aggressors who inflict this harm are not identified, at least initially. This differentiation is made because the two situations are handled differently, both for those affected individually, in terms of physical and mental health, as well as for their environments, health and safety services, and ultimately for society as a whole.

On the other hand, there are disasters and catastrophes that occur due to natural causes. In this case, Benyakar (2002) indicates that they can be foreseeable or unforeseeable. Being foreseeable means that it is possible to anticipate some kind of preparation and measures, but it does not guarantee that predictions will be able to control these situations or that it will be possible to resolve them with the means available, for example, in the case of meteorological phenomena. (Benyakar, 2002)

We would like to make a distinction here that adds a point of complexity to the concept of an emergency situation, namely that of organisational crises. This is due to the context in which we currently live, in which organisations play a major role in social development and stability, in an interconnected and globalised context.

ISO 22301 defines crisis as “a situation with a high level of uncertainty that affects the core business and/or credibility of the organisation and requires urgent action”.

In this sense, crises can affect personal, material or economic resources, infrastructures or operations that are essential and indispensable for the organisation's activity, and can even have repercussions on its reputation. The level of impact of the crisis triggered could make it difficult to deal with it, generating serious damage and potentially jeopardising the continuity of the organisation or its reputation.

There are many potential events or circumstances that can lead to a crisis. Being able to identify them, as well as the synergy between them, helps us to plan and develop an adjusted approach, facilitates their management, and allows us to develop action plans.

The complexity of organisations themselves, as well as of their stakeholders and contexts, is increasing exponentially. Scenarios and environments are becoming increasingly complex and dynamic, whereby they are defined by uncertainty and volatility, which are therefore also the hallmarks of the crises that arise. As a result, managing them is extremely complex due to the factors to be taken into account and greater technical and mental preparation, in terms of the knowledge and specialisation of the teams and professionals responsible for dealing with them.

It is important to highlight the duration of emergency situations or crises over time, their magnitude, potential damage and consequences, because planning and designing intervention measures depends on this. We could say that they can be one-off situations, understood as being isolated circumstances that can be dealt with. In principle, their impact does not have major consequences and would not be long-lasting.

On the other hand, there are those whose cause is isolated but whose repercussions are prolonged over time and even irreversible, and affect several areas at the individual, family, organisational or social level, such as the death of a person. Furthermore, circumstances also arise in which the situation that causes them and their consequences are prolonged over time and require a complex approach, such as humanitarian crises, chronic illnesses or armed conflicts.

One of the most important and defining characteristics of emergency and crisis situations, which should not be overlooked, is that they present both danger and opportunity. Generally, these situations have negative connotations, as they represent “loss” or threat to some extent of the initial situation or context. However, a well-managed crisis or emergency situation can lead to a resolution of the situation, with a correction of the initial situation and a learning process that lays the foundations for the future. In addition, from a leadership point of view, optimal and effective crisis management can reinforce leadership.

All of the above situations, as well as crisis and emergency situations, occur in context. Context is a major factor in planning an approach to addressing such situations. For this reason, we will take a look at the types of context.

3.2. THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTEXT. VUCA AND BANI MODELS.

Knowledge of the context, the scenario or the reality in which we act is necessary in order to plan the approach to the task, action or intervention to be carried out. At this point, it is important to point out two models of context that are currently being proposed, because knowledge of some basic characteristics helps us to define this plan of action, since we start from a high level of uncertainty, when we are dealing, as we are talking about here, with sudden situations that reflect this uncertainty and immediacy. We are talking about the VUCA and BANI environments.

The scenario in which we are currently operating has recently been classified as a VUCA environment. An environment characterised, moreover, by immediacy, the need for adaptation and constant learning. The VUCA concept has military origin, a term devised at the US Army War College during the 1990s. The VUCA model is based, on the one hand, on the knowledge of the context and, on the other hand, on the predictive capacity that we can have before it occurs when planning an action plan to develop a task or carry out an activity.

In addition to all this, we must mention the added impact and uncertainty due to globalisation, the influence of new technologies and social networks, which bring an aspect of urgency, if that is even possible, due to real-time feedback. The characteristics of the VUCA environment are:

- V: Volatility: due to the high speed at which events occur and changes happen.

- U: Uncertainty: this refers to the difficulty or impossibility of being able to predict effects, and is derived in part from the volatility referred to in the previous point.

- C: Complexity: refers to the number of variables and factors that can be identified, as well as the synergies between them and the results that can be consequently obtained.

- A: Ambiguity: in relation to the lack of clarity of a scenario or the lack of knowledge or information we may have about the context, situation, precedents or predictability of the scenario. Moreover, we must remember the importance of synergies.

However, a new scenario appears in the current panorama, the BANI environment, which arises from the presence of variables or factors within the current framework, and to which VUCA does not refer.

Although defined in 2016 by Jamais Cascio, in “Facing the Age of Chaos”, the BANI environment came about to explain these variables or factors that are present and to better understand the scenario that was beginning to emerge, but especially acquires greater importance at the moment in which we find ourselves at a global level, with the latest events that have occurred, especially since the pandemic. In this sense, the BANI environment has its own identity, marked by chaos and confusion.

- B: Brittle: refers to the weakness that most systems, organisations or societies may present, taking into account the volatility indicated by the VUCA model, i.e. they are less strong than they appear to be, because they can collapse if an unforeseen event arises that they do not know how to deal with or the response is late. In this respect, most organisations generally appear to be more consistent than they are in reality, so we can become overconfident and fail to come up with timely solutions.

- A: Anxious: refers to the fact that facing new situations with which we are not familiar generates anxiety and fear. To minimise these feelings, we constantly seek feedback and information that can give us certainty, making it an ideal breeding ground for chaotic situations to occur if the feedback is absent or incorrect. A crucial factor is introduced here, one that involves current paradigms of greatest relevance and greatest management challenges, which are the emotional factor and mental health, its influence and repercussions.

- N: Non-linear: refers to the probability that there is no direct relationship between cause and effect. It tells us that there may not be proportionality or balance between cause and consequence.

- I: Incomprehensible: refers to the fact that we find ourselves in an environment that we cannot explain with the knowledge we have, we can consider it illogical, because it does not respond to known patterns on many occasions. This therefore makes it difficult to understand what is happening.

Such scenarios make it necessary for us to adapt as quickly and efficiently as possible to changes. One of the main indications that we find in the face of this is the need to deepen our knowledge of the initial situation, and to have as much information as possible about the situations we have to deal with, the capacity to adapt to change, flexibility and continuous learning, as well as a clear strategic vision and leadership, which provide stability and the capacity to react to the circumstances described, as they affect all levels: individual, organisational and societal.

However, a change is taking place in which not only learning and adaptive capacity are taken into account, but the definition of BANI environments also puts the focus on concepts like anxiety. This reflects a point of view hitherto little emphasised: people at a more individual level, which is crucial and of great importance for facing these types of scenarios. All the systems, organisations and teams that we can identify are made up of people, but also the entities themselves may respond with anxiety to certain circumstances, such as, for example, the behaviour of the financial market.

Defining the new scenarios and the new concepts that arise helps us to better understand the environment in which we find ourselves, and to develop the necessary strategies or capacities at the individual, organisational and social levels in all areas (health, employment, social aspects, education, security, among other factors), in order to effectively face new challenges that arise, such as new leaders, the importance of mental health or the influence of the psychological factor.

4. THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS UNDER STRESS. THE INFLUENCE OF EMOTIONS AND THE PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTOR.

Critical incidents, emergency situations or crises are events that have a great emotional impact, capable of affecting the usual coping mechanisms of individuals or groups, including the professionals in charge of dealing with these emergency situations, who behave effectively in the face of such events. Effective in this case is understood to mean carrying out their work in a way that manages the emotional impact.

Most professionals facing emergency situations are likely to experience emotional reactions to these circumstances, especially if their profession implies that they may face them on a recurrent basis, as is the case of health teams, FCSE professionals, firefighters, and other emergency teams, risk departments or teams or professionals dedicated to solving emergencies or organisational crises.

Prieto-Callejero et als (2020) point out that “every disaster represents a traumatic event in the lives of individuals and communities. Psychological trauma following an unpleasant event not previously experienced provokes a psychological crisis that is expressed through multiple feelings and is related to the characteristics of the individual (sensitivity, perceived support, previous experiences, among others), the type of phenomenon and its characteristics, as well as the social and cultural context”.

This is why psychological preparation of this type of professionals is fundamental, as it is not only about managing the emotional impact, risk assessment and high stress for effective performance, but also the recovery after this emotional impact and the minimisation of the possible consequences at a psychological level.

At this point, it is important to point out that preparation of this type of professionals must be constant, updated and in accordance with the nature of their work, the context and the organisation of which they form part. In this sense, we can find differences in the preparation required by, for example, a financial consultant, the FCSE, or emergency teams, such as health workers, to give just a few examples.

According to the model presented by Espinosa (1981), the basic areas on which preparation of a professional intervening in emergencies is based form a whole, in which one is supported by the other for comprehensive preparation. These areas are:

- Technical-tactical training: Theoretical and technical knowledge of specific professional aspects relating to the performance of their work.

- Physical training: Healthy and optimal physical development and maintenance. In particular, those professionals assigned to emergencies require physical training, due to the nature of the situations they face.

- Psychological preparation: Knowledge and training of coping strategies in professional situations or actions and prevention of possible psychological consequences derived from them.

Next, we will briefly discuss the emotional reaction to emergency situations in order to highlight their complexity.

4.1. THE ROLE OF EMOTIONS IN DECISION-MAKING.

Reaction to the emergency or crisis begins as soon as the situation, the context and its characteristics are known. At that point, at the individual level, an assessment of the situation and the threat it poses a priori is already made.

The emergency alert itself may cause the activity that was being carried out to come to a standstill and have to be adapted to the new situation and its requirements in order to deal with it. It is at this point that the greatest emotional triggering takes place, and the individual cognitive, psychological and physical resources available to cope with the situation are brought into play.

An assessment is made of self-efficacy, i.e. whether the resources available to the individual in the first instance, and collectively in the second instance, are sufficient to cope with the situation. Here, prior experience or training and preparation are crucial for coping strategies and resolution of the situation. Learning therefore plays an important role, as the subject's previous experiences, whether real, simulated through training, education or information, the expectations of others or the pressure to perform well due to the nature of the job, all influence the perception of threat, and ultimately, reaction to it.

Here, the role of leader is crucial. Faced with this type of situation and, specifically, the point we are describing at here, leaders not only have to deal with this individual evaluation and perception, but also with the group, the team and the resources available to deal with it, bearing in mind that the aim is to resolve it effectively. In other words, the level of stress they face is higher since the leadership of the group, the burden of decision-making, the decisions themselves and the outcome of those decisions, falls on them.

Fidalgo Vega points out that, during this process of perception and evaluation, the subject's emotional experience of the situation occurs in parallel. In these situations, a degree of emotional arousal may be reached that renders people unable to make decisions and perform behaviours appropriately. (Fidalgo, 1999)

If there is no perception of self-efficacy and effectiveness in the situation, and the management framework that we propose, i.e., decision-making and team management across all the aspects that we have discussed so far, since at this point, the team and its functioning, as well as the recognition of the figure of the leader, must have a remarkable maturity.

This feeling of effectiveness and self-efficacy in the face of the situation must be felt both by the leaders and by each of the team members. We are talking about the fact that, for the team to function effectively and to be able to resolve the situation that arises, it is necessary for each of the members to carry out their work properly, since they are all necessary and, in most cases, their functions are interdependent and connected, in such a way that they lead to the fulfilment of the objectives. The same applies not only to the members of the team, but also to the different teams or entities, which must work in cooperation to achieve this objective. Each one must do its work so that the work can be completed and the purposes for which they are called upon can be achieved.

If this is not the case, there must be space for group management, organisation and direction in which the objectives and guidelines to be followed are set, and the group can begin its work. At this point, the leader as role model, and the members of the group or team, seen as reference points, mainly because of their experience or technical capacity, become more meaningful and relevant for less experienced members, either in their work or in the team.

4.2. THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS IN EMERGENCY AND CRISIS SITUATIONS.

Decision-making in emergency or crisis situations, due to the nature of these situations, as already mentioned, takes place in an extraordinary way in a framework of uncertainty and high stress, which gives them special importance.

When it comes to emergency or crisis situations, there may be an emotional impact, which must be managed appropriately, and for this, technical, mental and physical preparation is key. If this management is insufficient or inadequate, it may lead to reactions of anxiety, fear and panic, which can inhibit the individual's ability to respond.

The emotions triggered by an unexpected emergency situation may lead to a response of anxiety, fear or panic, which, if not well managed in terms of its emergence, intensity and duration, can lead to behaviours or conducts in response to this alarm, such as avoidance of the situation, panic reactions, aggression, blocking, the “tunnel vision” effect, and other negative reactions. These types of attitudes and emotions are produced by the occurrence of an emergency, and what it may entail, whether at the individual, group or societal level.

Cognitive appraisal of the situation occurs when a person has the capacity to manage the emotional impact, and to control the emotional reaction and arousal that the situation produces at all the levels indicated. It is at this point that an assessment of the situation, as well as the context and the resources available to us, is made, and the situation is considered by the teams and the leaders in order to plan an approach to addressing it, and the defined action plan is initiated.

This is one of the main functions of the leader, if not the main function, since decision-making and the exercise of leadership and what it entails, discussed in previous sections, could be considered as the definition of the leader's work.

“Stress focuses attention on the present moment, inhibiting long-term response systems” (Alvarez Maestre, 2016). In addition to achieving adequate concentration and attention in the short term, it is also necessary to have a strategic vision and foresight in the medium to long term, for which adequate emotional management is crucial.

It is important to emphasise in this respect that, in this type of circumstance, we are talking precisely about assessing the consequences and taking into account all the factors and variables involved in this type of situation, so that the sum of all this indicates once again the need for the preparation and training of professionals who are faced with this type of situation.

Decision-making in such circumstances is under extraordinary stress and pressure; however, all decisions made under stress in an emergency situation cannot be considered of the same nature or equal in terms of pressure, emotional demand or responsibility.

In addition, decisions may affect one or several individuals, be quick to resolve or involve a lengthy process, involve few resources or extensive deployment, and have individual, organisational or societal impact. In this sense, Alvarez Maestre points out that “not all work environments and scenarios are the same; some are more complex whereby stress is continuous and decision-making is not synonymous with profit or loss but with life and death, such as medical, military, security and judicial contexts”. (Álvarez Maestre, 2016)

We should point out that, when decisions have an impact on people's lives or living conditions, they place responsibility on others in some sense, and/or depending on the time available to make the decision, the information about the decision or the certainty of the consequence, influence the stress involved. Examples include the negotiation of individual or collective dismissals, or the deployment to carry out a rescue operation in the event of a natural disaster or to search for a missing person, although we could mention many more examples.

In this training on the decision-making process, the functioning of teams, processes and procedures, psychological coping strategies at the individual level, for each member, as well as at the group or organisational/institutional level, must be present, as this favours effective performance of each of the levels in this type of situation.

It is important to note that everyone involved in the emergency experiences the emotional impact and physiological, cognitive and behavioural reactions of the emergency, including the professionals involved, but it is assumed that they are professionals who are trained to deal with the emergency and have appropriate coping strategies. This is not to say that they do not suffer the emotional impact, but that they are prepared to manage it effectively and to be able to carry out their work.

Alvarez Maestre refers to studies such as that of Salgado and Megía, who in 2008 indicated that “prolonged exposure to stressful situations can affect individuals’ work performance” (Álvarez Maestre, 2016). In this sense, an intervention and subsequent intervention is necessary, such as debriefing and emotional defusing, to recover the emotional balance and adequate management of the experience both immediately and afterwards, to protect and prevent mental health and to avoid the appearance of PTSD or burnout, among other consequences, as well as part of training for a future intervention.

We will now take a brief look at some examples involving emotional management in emergency situations.

4.2.1. Uncertainty and risk assessment

Risk is the probability that certain loss will occur under a certain condition. (Fidalgo Vega, 1999). Risk refers to situations for which we start with certain information or precedents, meaning that it is possible to identify alternatives. We can therefore assess them, as well as possible outcomes and their consequences, irrespective of whether they ultimately occur.

Uncertainty, on the other hand, refers to situations for which we have ambiguous information, which makes it difficult to establish hypotheses and identify alternatives, so that we cannot measure the impact (Fidalgo Vega, 1999). This scenario affects the decision-making process and the capacity to act. This uncertainty influences not only the ability to make decisions or take action, but also human behaviour.

In people, the perception of this loss, which we discussed, is assessed on the basis of the idea of risk that is held and how it is perceived, i.e. the degree of threat experienced, and not the result of an objective assessment of the level of risk. If the person has information, preparation or is able to cope with the risk, this has a direct impact on the person's response.

Fidalgo Vega points out that “the individual makes an immediate assessment, considering their own health and that of others, whether the threat is known or unknown, and their confidence in their control and ability to cope with it or not.” (Fidalgo Vega, 199)

It is necessary to establish a starting consensus on the criteria, objectives, or key points with which one starts and what one wants to achieve. This lays the foundations to start organising the strategy to be followed. Consensus around this is crucial, as without a framework for decision-making, it is very difficult to ensure that teams, team members, and even coordination between them is possible, and effective work can be carried out.

In this sense, the work carried out by leaders is fundamental. It is here where the leadership process and the figure of the leader allow the framework to be given to decision-making and establish the bases on which the team will be guided in its performance. They also determine the direction given in terms of its objectives and functioning, and with respect to others, in the event that there are more participants. This is also crucial, since at the level of emotional impact, the perception of risk and uncertainty contribute to the responsiveness of both teams and the individuals that make them up. Managing this impact by leaders is the basis for both team members and the team to function as a whole, and to be able to develop the task they are entrusted with.

When the sensation of perceived risk appears in a context of uncertainty, even if there is information, it is very likely that the response given by individuals at an individual level will not be the most appropriate way to deal with the situation. This is due to the fact that the perception of risk for the subjects is mainly subjective, and spontaneous behaviours aimed at overcoming these risks may appear, such as anxiety, blocking, panic or flight, among other types of conduct.

When this set of behaviours occurs in the presence of more people, the tendency is to imitate the behaviour of others. The phenomenon of imitation occurs because there is an already constructed response. It is not necessary to evaluate this, but only to execute it, which in those moments when there is no time to make a cognitive evaluation, facilitates an alternative response to the situation. There may also be phenomena of social inhibition or dilution of responsibility.

In such circumstances, it is possible that panic could occur, which would be the catalyst for a situation that would overwhelm the reaction capacity of the teams. This applies whether we consider the team itself, affecting its own performance, or whether this panic phenomenon occurs outside the team, for example among those affected, which could limit or overwhelm the response capacity of the emergency teams.

4.2.2 The panic phenomenon

Panic is a consequence of assessing a situation in which we feel helpless and overwhelmed. According to Fidalgo Vega, it can be defined as a “group of people who react with feelings of alarm, whether the danger is real or supposed, and with fearful, spontaneous and uncoordinated behaviour”. (Fidalgo Vega,1999)

It is a factor that aggravates individual risk, due to the loss of the feeling of self-efficacy, i.e. of being able to face the situation. It also adds danger to the situation, because panic is a phenomenon that is “contagious”, which can lead to situations of greater danger, added to the already existing one. Generally, when faced with a situation of real or imagined danger, we respond with anxiety and even fear. This is an adaptive response, as it allows us to assess the danger we face and our ability to respond to it.

In general terms, we can say that feeling anxious or afraid can be positive in the sense that it is adaptive. However, when fear is disproportionate, it does not allow us to cognitively evaluate the danger or possible alternatives, so it can lead to maladaptive behaviours that can worsen the situation, pose a risk to ourselves or to others, as in the case of flight. From that point on, it can become “contagious” so that it is no longer an individual response but a collective response. (Fidalgo Vega,1999)

Collective behaviour is spontaneous and generally subject to self-created rules that emerge at the time. Fidalgo Vega points out that people conform to norms that define, in a variety of situations, the expected behaviour at any given moment. However, if an emergency were declared, the rules that governed the previous situation would be suspended and behaviour would no longer be orderly and predictable. (Fidalgo, 1999)

The phenomenon of panic is generated by a precipitating factor, whereby people feel intense fear. Social expectations and norms do not fit or explain the situation, so each individual, acting just for their own benefit, seeks to avoid or get out of the dangerous situation, and thus the situation may involve greater risk. If not managed in its early stages, panic can result in a chaotic situation.

The phenomenon of panic becomes collective behaviour, mainly due to the phenomenon of “contagion” and response imitation. This contagion is a process in which one person influences another, and they in turn influence another, and so on, in rapid succession, whereby there is often emotional escalation in a context of uncertainty. It involves the diffusion of emotion and imitation of behaviour from one individual to another.

This can lead to an increase in the intensity of the behaviour, which can aggravate the emergency or crisis situation from which we started. When we find ourselves in scenarios of pain and there is also uncertainty, if we are in a group, paralysing emotions or behaviours of escape, flight, pain or anger can occur, especially in situations of death or the possibility of life-threatening situations. In these situations, it is crucial to manage the emotional impact in order to prevent the situation from getting out of hand.

In these initial phases, the appropriate management of the emotional impact of the situation, the role of leaders and reference professionals is fundamental. They are figures who contribute through their actions and example to reducing uncertainty and, especially in the initial phases, favouring the control of emotions, the reduction of anxiety and fear and therefore panic. This helps to control the situation and enable it to be dealt with in the terms set out at the outset.

In this sense, the role of leaders and team leaders or those affected is fundamental, not only so that panic does not become “contagious”. It is also essential so that there is no emotional contagion, whether of positive or negative emotions, since this emotional connection can occur and affect the performance of the task. It is important to manage emotions appropriately, since positive emotions can be counterproductive if they are euphoric, just as poor management of negative emotions can also affect the development of the situation.

5. THE IMPORTANCE OF LEADERSHIP AND LEADERS IN CRISIS AND EMERGENCY SITUATIONS.

As we have been analysing throughout the text, leadership and the role played by leaders in teams and organisations is fundamental. This role is even more relevant when it comes to crisis or emergency situations.

Leadership in emergency, crisis and even critical situations has a significant impact on how they are approached, and thus on how the team, each of its members, the organisation or community, and the affected people and their stakeholders deal with and recover from the situation.

In this sense, the aim is for leaders to direct and guide their team in these moments of ambiguity and uncertainty, and exceptional situations. They seek the best solution to the situation, minimise the negative impact it may have or the consequences, and establish the basis for recovery or search for the best possible balance or adaptation to the situation. It is about leaders being able to adequately manage the given situation and the stress generated by it, based on their experience, skills, abilities, preparation and previous training.

Adequate management of the situation and achievement of the objectives set or correct management of adapting objectives, in the event that the first approaches cannot be achieved, contributes to strengthening leadership. This also strengthens the organisation due to the learning that is obtained from managing the situation, and provides a solidity for the future that allows it to focus on and better manage possible similar situations that may occur. Leaders also reinforce the image and reputation of the organisation they represent.

They have a key role to play here, as they are in principle responsible for implementing this learning or contributing their findings to it, as well as implementing new strategies to mitigate future risks and building an adaptive and resilient organisational culture.

Different scenarios and risks can be considered, allowing for adequate training and information of those involved. It is also necessary to evaluate the intervention carried out in order to establish learning, recovery strategies and balance, both of the situation and of the intervention, as well as adequate management of the emotional impact of the intervening professionals, before, during and after the given situation. Developing a good crisis management plan can be the difference between an effective crisis response and an ineffective one.

It is also essential to highlight the role of leaders in managing the emotional impact of emergency and crisis situations, not only by managing uncertainty, but also through the guidance and direction they give to the team in moments when uncertainty is one of the most important issues for both the teams and their individual members. This is true especially if these are situations with a high emotional impact, even if they occur for a longer or shorter time period, or they are situations that may seem “minor” a priori, but which, if prolonged over time, may also affect and have consequences at the psychological level, and therefore on the performance of both the team and its members.

In view of this issue, stress management and emotional impact, it is important to highlight the communication of bad news and its management, such as the fact of not achieving objectives or the possibility of not achieving them, and to continue reinforcing and leading the team, despite not receiving good news or dramatic news. This is a point at which communication and management of the team's emotions, from a realistic approach, is fundamental. Ex-post management, evaluation of the situation and areas for improvement and learning are also key.

One of the hardest realities that teams can face is grief management. This mourning can be both in the face of the loss of partners and in the face of the reality that we may encounter, for example, in natural disasters, violent deaths or other such situations. In this sense, the leader has a crucial and prominent role, as they are the point of reference. In this type of situation, managing the situation starts from the moment the situation becomes known, the communication, the clarification of what happened, the feeling of injustice, and the emotional management of this grief. This occurs both at the moment the news is discovered or the reality is being experienced, and afterwards, when addressing the team and those affected or the community or society in which the team operates.

In crisis situations, leaders are the driving force and support for the team, the organisation and also for those affected. They play a crucial role in how the situation and the team evolves, as well as in recovering equilibrium or adapting to the new situation in the aftermath. This highlights the importance of optimal preparation, experience and the role of leaders in the sense that they are role models, they lead by example, and they are considered to be “teachers”. In addition, they act as supports and “screens” when it comes to the emotional impact of the situation on their teams, which gives them a special role in the team. One of the great challenges of exercising their leadership is to make timely decisions, to give direction and objectives to the team, in order to tackle the situation. This is in addition to constantly evaluating how the situation is developing.

6. LEADERSHIP IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS. APPLICABILITY TO THE GUARDIA CIVIL.

The Guardia Civil is a public security force that is military in nature and national in scope. It forms part of the Spanish State Security Forces and Corps (FCSE). According to data from the Armed Forces, a total of 46,000 agents are dedicated to the tasks known under the Corps' Special Service, which is practically 62% of all personnel, and 25,000 specialists (34%) are dedicated to the specialities, while the rest of the members of the corps are dedicated to command and management tasks. (Guardia Civil, 2024)

The Guardia Civil is a hierarchical entity, clearly defined by its organisation and organisational chart, i,e., both for professional careers and for organisational and territorial distribution, since the Guardia Civil has a presence throughout the national territory.

Although it is a hierarchical entity, and its functions include some of those mentioned above, it is important to bear in mind that it is a dynamic organisation whose functioning and management also responds to issues relating to the organisation itself, such as appropriate management of personnel. At this point, leadership processes take on special relevance, taking into account both the characteristics of the organisation and its functions.

In this sense, and as the data shown above indicate, some of its professionals have command and management responsibilities and functions. At this point, the leadership process, the style and role of the leaders in their teams, whether they have more or fewer members, the values of the organisation, as well as the vision and mission of the organisation, of which they form part and which they represent, become especially relevant, since the members use this basis to guide their professional performance.

We can classify the likelihood of the Guardia Civil facing emergency situations, uncertainty and risk, both for others and for themselves, as being quite high, given the nature of their work. Team leaders in this case are often confronted with such situations, making decisions under stress in critical situations, as this is implicit in their work.

An important point to highlight in dealing with emergencies in terms of the FCSE and the emergency teams, in this case, the Guardia Civil, is that they are usually the first to arrive on the scene of the emergency or crisis. Therefore, their intervention in those first moments is crucial for how the specific situation evolves, due to the high uncertainty at the time, the necessary assessment of the situation and the risk in order to propose appropriate intervention, as well as emotional management of individuals, the team and even those affected.

Following this vein, we emphasise the importance and urgency of addressing the psychological factor and the mental health of the professionals who form part of the corps, in terms of prevention, early detection and intervention, in those cases or dynamics, in which it is considered necessary. As part of this approach, the role of leaders and of the institution as such is fundamental.

In addition to this, it is a profession that also has psychosocial risks associated with it, such as responsibility for the lives of others and oneself, shift work, night work, difficulties in reconciling work and family life, continuous exposure to high stress, risk to one's own and others' lives, recurrent exposure to situations of high emotional impact, among other consequences. As we have previously indicated, this makes a mental health approach both necessary and decisive.

Due to all of the above, it is important to continue reinforcing the preparation and training of Guardia Civil members on leadership issues, so that the teams and their leaders reach a maturity that leads to their own management as teams, as well as to face these types of situations in an effective manner. These circumstances can be approached as opportunities for growth and improvement, both for leaders and their teams.

As we can see, the leadership process and the role of leaders in the case of the members and professionals who make up the Armed Forces is not only reduced to the responsibility for their teams, whatever the scale, or the number of work team members, but also to coordination with other teams. This applies whether the other teams also belong to the Guardia Civil or other entities, such as health and emergency teams, firefighters or others, as in the case of emergency response, or work with other national, international or supranational FCSE.

But above all, the Guardia Civil and its members have a more far-reaching commitment, since this organisation represents institutional leadership in society, and this role is inherent for each of its members, regardless of their rank and scale, in terms of their responsibility.

The professionals and members of the Guardia Civil not only carry out the duties of their post, but also have social value and function due to their proximity and accessibility to the public. The Guardia Civil’s members, leaders and representatives are all subject to this institutional leadership, as they not only contribute to leading the organisation but also to its building reputation in the society or community in which it operates. Institutional leadership addresses the role and meaning of the institution in society. In the case of the Guardia Civil, its role in society is relevant due to the different tasks it performs, its vocation of service and its close and accessible service to citizens.

Emergency situations, crises, moments of uncertainty are times when decision-making, leadership and the figure of leaders and their role are most relevant. Along these lines, they can be understood as critical moments for the leaders of FCSE teams, in this case the Guardia Civil, in which they are subjected to added pressure, consciously or unconsciously. This means that they are also “evaluated” to a certain extent, in these circumstances. In the case of the Armed Forces, this evaluation comes from the team, from the institution itself and, ultimately, from the community or society in which it operates, which adds an extra component of pressure on the leadership, derived from institutional leadership.

7. CONCLUSIONS

Leadership in crisis situations is undoubtedly one of the most complex challenges leaders face in their role. It also requires them to inspire, motivate, support and understand others in difficult and even critical moments. Leadership in crisis situations requires them to manage the situation appropriately, so that the decision-making process and the guidance they give to the team, as well as their own emotional management and that of the group, allow for the best approach to the situation and its resolution.

Prior to this emergency or crisis situation, there is a previous evolution and development of the team and therefore of the leadership. Let us remember that leadership processes cannot happen without followers, just as teams are dynamic and present continuous challenges, which must be managed for their correct functioning, cohesion and commitment. It is important to highlight that there is no one style that is better than another. Rather, in order to achieve effective leadership, it is necessary to adapt the leadership style to the task, the team and the context, in order to guide it appropriately to achieve the objectives set.

In dealing with all kinds of challenges, but especially in dealing with crisis and emergency situations, it is important to know the context in which we find ourselves, in order to be able to propose appropriate strategies for managing the situation, as well as the resources necessary and available to do so. Leaders must maintain a long-term strategic perspective, looking not only at the immediate needs of the given situation but also at the short-, medium- and long-term development of the situation, as well as a holistic and strategic view of the situation, identifying dangers and opportunities.

One of the characteristics of emergency and crisis situations, and even more so in today's times characterised by a global village approach and interconnectedness, is that they involve unpredictable and sudden changes. As such, leaders must be able to adapt to new demands. Adaptability allows leaders to adjust both their perspective and strategy, if necessary, according to how the situation evolves and its nature, and the characteristics of the team and its components, as well as the direction and objectives set.

These issues are accentuated in emergency and crisis contexts because of the added factor brought by the role of emotions and the psychological factor in managing risk and uncertainty, which directly affect decision-making.

An adequate leadership process in crisis situations implies a constant process of learning and training. A crisis leadership process should anticipate situations that we may face in order to begin to develop a strategy or emergency plan that allows for an effective and adequate response by all those involved, and allows us to avoid it or, if this is not possible, to minimise the consequences.

Adequate communication is key throughout the leadership process. However, in a critical situation, this becomes crucial and decisive. In this sense, communication during a crisis must be action-oriented, i.e. focused on giving direction and guidance on how to respond to the challenge that has arisen. Leaders should provide concise instructions and guidelines to all stakeholders involved in the situation to address it and coordinate the response to the emergency. The information and guidelines provided can have a significant impact on how a crisis is managed, including at the emotional level, and can help to alleviate the uncertainty, anxiety and fear that are associated with such situations.

Effective leadership in crisis and emergency situations involves not only making decisions and guiding teams and team members appropriately to achieve goals, but also managing the emotional impact, communicating bad news or the possibility of not achieving objectives, and especially managing grief, if necessary.

During an emergency or crisis situation, one of the most important facets of leaders is their own and others' emotional management, i.e. they must manage the emotional impact that the situation has on them and on their team members and on those affected, issuing appropriate guidelines and instructions, communicating effectively and filtering information in an optimal way.

In this sense, leaders act as a “screen”, a kind of filter, between the feedback from the situation and the emotions it provokes in the team. This allows the team to focus on its task, but at the same time, leaders must provide support in this sense, attending to both the emotions and the needs they may have to carry out their work, in terms of measures, resources or possible alternatives for resolution.

Understanding their teams and even sharing emotions strengthens cohesion and identity, and gives shared meaning and commitment to the task for both teams and leaders, which strengthens them in their roles. Let us remember that leadership has no place if there are no people who believe and trust in those leaders.