Juan Manuel Ramos Santamar a

Lieutenant Colonel of Guardia Civil

PhD student in the European Union Doctoral Programme at UNED1

Master's Degree in Military Sciences in Security and Defence

Jihadist terrorism as a latent threat in the European Union: capability vs. intentionality

[1] Email: jramos606@alumno.uned.es

Jihadist terrorism as a latent threat

in the European Union: capacity vs. intentionality

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION. 2. ABILITY TO ATTACK. 2.1. Attacks in the European Union: lethality vs. modality. 2.2. Attacks thwarted vs. attacks carried out. 2.3. Attacks by country: hotbeds, jihadist networks and military intervention against Daesh. 3. INTENTIONALITY. 3.1. The facts: arrests and suspected radicalisation. 3.2. The cycle of hate. 3.3. Jihadist radicalisation: a kaleidoscope of factors. 3.4. The external threat: ISIS-K. 3.5. Analysis of results. 4. CONCLUSIONS. 5. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES.

Resumen: En los ltimos a os, el n mero de atentados consumados en la Uni n Europea atribuidos al Daesh ha disminuido de forma significativa, lejos de la cantidad y letalidad de los a os 2016 y 2017. No obstante, la cifra de conspiraciones terroristas frustradas por las Fuerzas y Cuerpos de Seguridad, el n mero de radicales presentes en determinados pa ses, unido a las actividades terroristas del ISIS-K en Alemania o Francia, as como en aquellos otros pa ses que el grupo considera apostatas y por tanto enemigos-, tales como Rusia, Ir n, o Turqu a, permiten inferir que la amenaza yihadista es alta y continua latente.

A ra z del presente estudio, se observa c mo las redes yihadistas promueven la radicalizaci n entre los sectores m s vulnerables existentes en las sociedades paralelas que florecen dentro de los denominados hotbeds, aprovechando el contacto personal y la cercan a. Se verifica que los doce pa ses de la Uni n Europa y el Reino unido donde se han sufrido atentados presentan, c mo caracter sticas comunes, adem s de la presencia de las redes, la existencia de combatientes extranjeros europeos, y/o haber participado militarmente contra el Daesh. En dichos territorios, el ciclo de odio fruto de la din mica ataque-xenofobia-reclutamiento posibilita la radicalizaci n.

Si se quiere acabar con la amenaza yihadista, hay que trabajar no solo en la neutralizaci n de la capacidad de atentar, sino especialmente, en una forma efectiva de encarar el ideario terrorista que es capaz de radicalizar y seducir a individuos que se unen a la organizaci n y llegan a matar en su nombre.

Abstract: In recent years, the number of completed terrorist attacks on European Union soil has decreased significantly, far from those committed in 2016 and 2017, in terms of quantity and lethality. However, the number of foiled plots by law enforcement agencies, the quantity of radicals presents in certain countries, coupled with terrorist activities under ISIS-K in France or Germany, and in other countries considered apostates by Daesh, and, consequently, enemies, such as Russia, Iran or Turkey, reveal that jihadist threat is both high and latent.

Resulting from the present research, it is observed how jihadist networks boost radicalization among those more vulnerable in parallel societies , that flourish within the so called hotbeds, taking advantage of face-to-face contact and closeness. In this way, it is verified that the twelve European Union members and the United Kingdom that have suffered terrorist attacks on their soil, have common characteristics, such as existing jihadist networks, having produced European foreign fighters and/or having participated in the military intervention against Daesh. In those territories, the cycle of hatred that stems from the attack-xenophobia-recruitment dynamic, enables radicalization.

If we want to put an end to the jihadist threat, not only has the capacity of attack to be dealt with, but also find an effective way to cope with the ideology, the one that is able to radicalize and seduce people that end up joining the ranks of the organization, killing in its name.

Palabras clave: Radicalizaci n, factores pull, factores push, hotbeds, redes yihadistas.

Keywords: Radicalization, pull factors, push factors, hotbeds, jihadist networks

ABBREVIATIONS

UNGA: United Nations General Assembly

BBC: British Broadcasting Corporation

CC: Central Issue

EUROPOL: European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation

IAEM: Institute for Advanced Military Studies

IRU: Internet Referral Unit

ISIS-K: The Islamic State - Khorasan Province

KTCC: Kurdish Training Coordination Center

NATO: North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

UNDCP: United Nations Development Programme

POOLRE: Pool Reinsurance Company

RAN: Radical Awareness Network

SAPO: S kerhetspolisen

SOUFAN GROUP: GS

TESAT: Terrorism Situation and Trend Report

TDP: The Defense Post

TST: The Strait Times

TRIVALENT: Terrorism prevention via radicalisation

EU: European Union

WC: Wilson Center

1. INTRODUCTION

The self-styled Islamic State, Daesh, rose to the spotlight for taking control of a territory the size of the United Kingdom (The Strait Times [TST], 2019), for its attempt to create a 'state' with governance structures, services and resource management (Bakkour and Stansfield, 2023, p. 126, 127), for its use of social media and propaganda (Tom , 2015, p. 11), and above all, for the wave of terrorist attacks carried out in its name in the West, particularly in Europe, on a scale and with a force that was unprecedented. The attack on the Bataclan hall in Paris and the mass shootings in Nice, Berlin, Stockholm and Barcelona are some examples of the terrorist threat that Europe has experienced in recent years.

The classic rationale in terms of measuring a terrorist threat is to count the number of executed attacks. This is understandable, as the attacks are in the public eye and are a measurable and tangible indicator. However, the approach of using this factor alone gives an incomplete picture, as the attacks carried out constitute just the "tip of the iceberg"; in other words, they are what is left after police forces have done their job, preventing and dismantling terrorist plots (Nesser, 2021, p. 143).

According to EUROPOL's latest Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TESAT) (2023, p. 24), two attacks were carried through to completion in the European Union (EU) in 2022, and three in 2021. Taking into consideration the above, and given that the number of actual attacks in Europe is relatively low, can we conclude that the terrorist threat in the EU is likewise low? This is the central question of this article, which we attempt to answer by analysing the problem of jihadist terrorism in Europe and identifying the factors that contribute to combating it and to its continuity.

Regarding the concept of threat, it can be seen as the product of the capacity to attack, of the conscious will to do harm (Couto, 1980, p. 329). To this effect, a specific situation is capable of creating a threat if the agent has the potential to cause harm, and if they intend to do so (Escorrega, 2009, p. 6). Assessing the threat in terms of accomplished attacks alone ignores the intentionality[1], i.e. the conscious will to do harm.

In the light of the above, several indicators will be analysed[2] that measure the capacity to attack, such as the different modalities of attacks, and the evolution from complex attacks (with weapons or explosives) to more simple or rudimentary ones (bladed weapons). This will be followed by a discussion of the other threat factor, intentionality. We will look at the potential pool of people willing to adhere to the jihadist ideology, and those who end up making the leap from cognitive radicalisation to the materialisation of violence. In the results analysis section, we will comment on the results based on the indicators. And last, in the conclusions, I will answer the central question posed above and comment on the current situation in Europe.

2. ABILITY TO ATTACK

I will begin this section by highlighting the importance of the paradigm shift in jihadist terrorism. The pioneer of this new approach was Al-Qaeda chief Mustafa Setmarian, who advocated individual jihad as a way of avoiding leaking plans and police action (Rojas and Carri n, 2017). It marked a shift from group terrorism, which was more likely to be detected and had a certain hierarchy, to a more fluid terrorism based on the initiative of the individual or small cell.

This individual jihad, together with the simplicity of planning[3] and the execution of low-cost terrorism, makes it extremely difficult to detect and prevent this type of attack, as Ramos (2019, p. 166) rightly points out. Notable too is the fact that Daesh itself claims attacks that have been directed, facilitated or inspired by the group, under the assumption that an attack inspired by Daesh is an attack by Daesh. (Osborne, 2018).

In fact, the probability of detection of a terrorist cell is directly proportional to the number of its members (Woo, 2017, p. 6). Individual attacks are therefore the least likely type of attack to be detected. In this vein, internet contacts, the purchase of suspicious substances and other similar activities may uncover a plot, enabling the attack to be foiled.

An example of the above is the thwarted attack in Cologne by German security services in June 2018 that led to the arrest of a Tunisian suspected of having been inspired by Daesh, revealing the importance of internet monitoring to uncover terrorist plots. It was also the first time a jihadist had managed to produce ricin by themselves following tutorials shared via Telegram (Flade, 2018, p. 1,3). Another similar event had taken place in 2017, when Daesh terrorists planned to detonate a bomb on a plane in Australia and, after that failed attempt, planned a chemical gas attack in Sydney (BBC, 2019).

2.1. ATTACKS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: LETHALITY VS. MODE

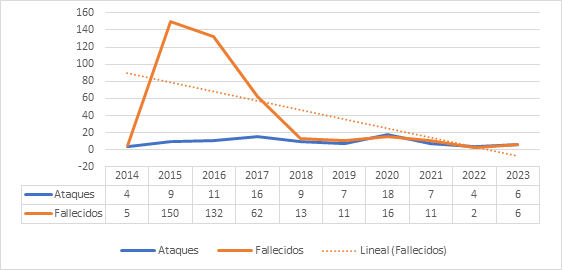

Figure 1 shows clearly how the number of victims increased dramatically as a result of the attacks Daesh began to perpetrate in Europe from 2014 onwards, coinciding with the proclamation of the Caliphate. As Ramos (2020, p. 55) states, the volume of attacks steadily and progressively decreased as the group lost control of territory thanks to military actions[4] and police pressure in Europe.

Indeed, the decrease in attacks and the large number of plots dismantled by the security forces show the importance of international cooperation. In this respect, EU legislative measures have been decisive, as they have made it possible to prevent travel to conflict zones, to control borders, weapons, explosives and their precursors, to monitor the internet, to create the Internet Referral Unit (IRU), and to exchange intelligence, among other activities, thereby optimising the police response to jihadism (Correia and Santamaria, 2021, p. 233). However, the number of attacks perpetrated over the period 2014-2023 has never been below four.

Jihadist propaganda and, in particular, the online instructions in Daesh's Rumiyah magazine, have also influenced the terrorists' chosen mode of attack. These guidelines have been used by small groups or individuals to "industrialise" terrorism (Pool Reinsurance Company [POOLRE], 2017, p. 4, 5, 24, 25).

Figure 1.

|

Evolution of jihadist attacks and number of deaths in Europe, 2014-2023

Note: Based on data from Igualada and Aguilera (2024, pp. 53-55).

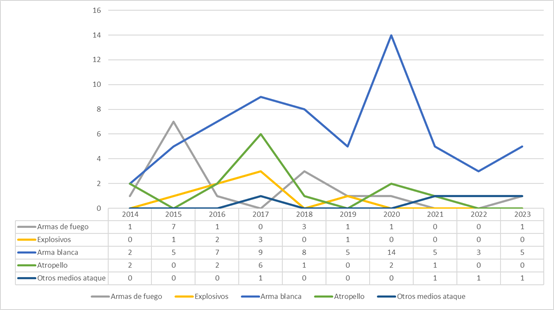

Firearms, a previously popular method chosen by terrorists, and very present in the attacks in Paris in January (Charlie Hebdo) and November 2015 (Bataclan), among others - became less used, and after 2018, there were just one-off attacks using this means[5] in 2019, 2020 and 2023. Similarly, since 2019 there has been no use of explosives in attacks.

The predominant mechanical means in the 1990s and at the beginning of the 21st century was group dynamics within terrorist cells, but now there is a clear trend towards individual perpetrators. Indeed, since the territorial collapse of Daesh, there have been no large-scale group jihadist attacks in Europe (Nesser, 2023, p. 8).

In terms of the means employed, the threat of the use of homemade explosives remains high, as evidenced by the many attacks in the EU, and especially those dismantled by law enforcement agencies that would have involved the use of explosives. EU regulations regarding the restriction of access to explosives precursors and the detection of suspicious transactions have contributed significantly to this new situation[6] (European Commission, 2020, p. 15).

Figures 1 and 2 show that in parallel to the group s loss of strength, territory and means, the attacks changed modality, and the use of weapons and explosives gave way to rudimentary tools[7], with a consequent decrease in lethality.

Figure 2.

Evolution of jihadist attacks by modality, 2014-2023

Note: Based on data from Igualada and Aguilera (2024, pp. 53-55).

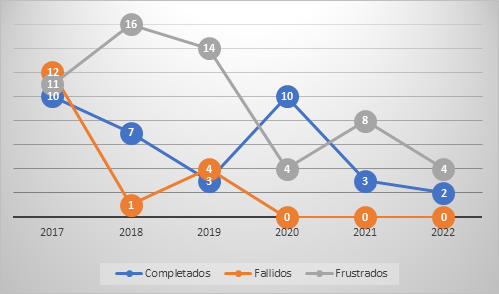

2.2. ATTACKS THWARTED VS. ATTACKS CARRIED OUT

Available data indicate that law enforcement agencies in the counter-terrorism context have been reasonably effective in terms of disrupting and neutralising terrorist plots involving chemical agents and firearms. However, analyses also show the vulnerability of societies to attacks that can be carried out using other tools as means, even if these are not "weapons" in the strict sense, including vehicles (Nesser, 2021, p. 153).

Ramos (2020) highlights the work of the police forces and the effectiveness of the military, which has contributed so much to reducing Daesh's capacity to carry out attacks abroad. Indeed, since the dismantling of Amn al-Kharji (external security) in 2017 thanks to military pressure, the organisation has proved incapable of devising, orchestrating and directing attacks of the calibre of those perpetrated in the period 2015-2017 (Hamming, 2023, p. 25).

However, as will be discussed in the section on external threats, in recent times, The Islamic State - Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) has managed to boost this once diminished capacity for international attacks by means of complex and targeted attacks.

With regard to thwarted and successful attacks, when EUROPOL data are considered (2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023), a comparison of the sum of thwarted and unsuccessful attacks shows that apart from 2020 due to the dynamics of the pandemic, the figure is higher than that of successful attacks (Figure 3). This highlights two extremes: the capacity of European police forces to thwart attacks and intentionality, i.e., despite this police effectiveness, there is still a will to do harm.

Figure 3.

Successful, thwarted and failed jihadist attacks in Europe, 2017-2022

Note: Elaboration based on EUROPOL data (2019, 2021, 2022, 2023)

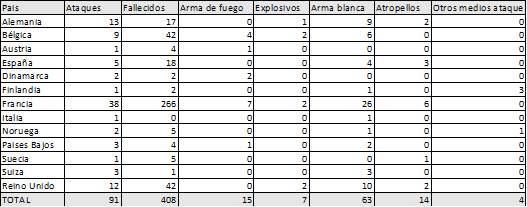

2.3. ATTACKS BY COUNTRY: HOTBEDS, JIHADIST NETWORKS and military intervention against daesh

Table 1 shows how attacks in the EU (including the UK) have occurred in certain countries, using a range of modalities from explosives to bladed weapons, as discussed in section 2.1 above.

Table 1

|

Jihadist attacks in Europe by country of commission 2014-2023

Note: Based on data from Igualada and Aguilera (2024, pp. 53-55).

The attacks have been concentrated in a total of 12 of the 27 EU countries and the UK. Is there a reason for this? Is there a reason why attacks have occurred in these countries and not in others?

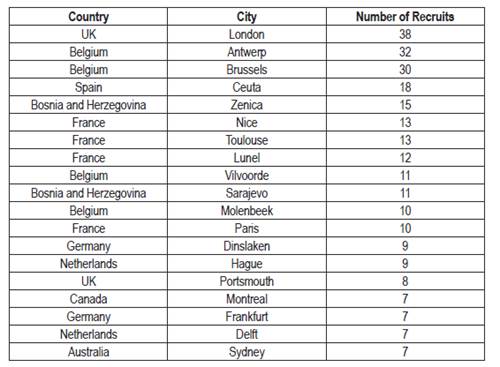

The Soufan Group's hotbed concept is extremely important in this respect. Ali Soufan and Daniel Schoenfel (2016, p. 19) explain how, in certain geographical areas (Table 2) and due to a number of factors, jihadist groups are more successful in their recruitment strategy. Notably, there is no single path that leads to radicalisation (Moccia, 2019, p. 34), but an amalgamation of factors at the macro-medium and micro levels[8], which when combined in different and multiple ways, can lead to violent extremism, as cited by Marcus Ranstorp (Radical Awareness Network [RAN], 2016, p. 1-3).

A clear example of this can be seen in the number of foreign fighters displaced to the conflict in Syria and Iraq, who can be identified as being mainly from certain regions: Saudi Arabia, Belgium, Tunisia, France, Libya, Russia and the UK, among many others. Continuing in this line of reasoning, there are also specific areas in these countries where the flow is located, which are the aforementioned hotbeds (Magri, 2016, p. 9).

To this effect, Perliger and Milton (2016) indicate how jihadist recruitment networks focus on specific areas to identify potential followers among immigrant communities, which are themselves under economic, social and other types of stressors. These authors also pointed to the importance of personal contact in recruitment: of 854 individuals who joined the ranks of jihadist organisations, almost 70% originated from cities where other foreign fighters had been identified (p. 26).

Table 2

|

Recruitment points for foreign fighters by city and country

Note: Perliger and Milton (2016, p. 27)

The Soufan Group (2015, p. 10, 11) states that the existence of these hotbeds is due to the personal nature of recruitment. Joining Daesh is an emotional as opposed to a rational act, with the presence of a close relative or family member in the radicalisation process often determining the outcome.

Research by Garc a Carola, Reinares and Vicente (2017) identifies previous links and personal contacts as essential factors in radicalisation, confirming the Soufan Group's hypothesis. The researchers' study of 178 subjects detained between 2013 and 2016 in Spain highlights two factors as being of paramount importance in understanding their radicalisation: First, personal or online contact with a radicalising agent, and second, the prior existence of social links with other radicalised individuals. This would explain why some individuals are radicalised and others are not, and also why this happens in certain areas and not uniformly among the Muslim population that is targeted for recruitment (p. 1).

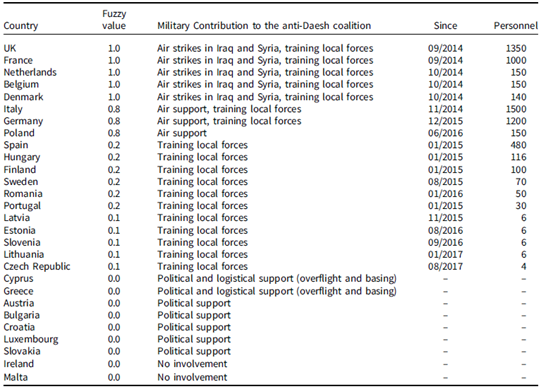

However, according to Nesser (2019, p. 17), aside from personal contacts, there are other factors that contribute to the continued high level of threat in certain European countries. An example of this is France and the UK, two countries with diametrically opposed approaches to integration: for the former, assimilation is essential, and for the latter, the policy of multi-culturalism. Despite these opposing approaches, the two countries have the highest threat levels in Europe. What other factors are at play? The answer is the policy of intervention in armed conflicts in Muslim countries (Table 3) and the dynamics of domestic jihadist networks in both countries that create international cells to represent Daesh or Al-Qaeda.

Table 3

Military contribution of countries in the International Coalition against Daesh

Note: Mello (2022)

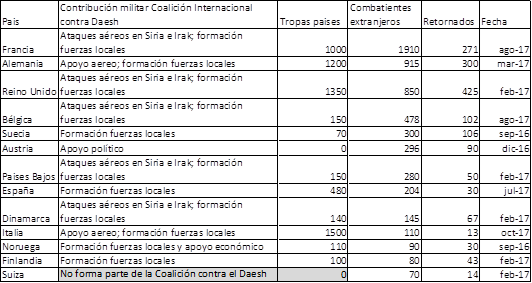

Table 3 shows the degree of commitment and contribution of each country in the International Coalition in its fight against Daesh. The countries that have contributed troops and made airstrikes have suffered the highest number of attacks (Table 1). Other countries that have provided technical assistance (training), such as Spain, Sweden and Finland, and Norway, have also suffered attacks. Switzerland is the only country that has not contributed to the Coalition but has suffered attacks, which is to do with the presence of jihadist networks there.

What about the other countries in Table 1?

Broadly speaking, the contribution by countries to the Global Coalition against Daesh can be classified into three categories (Mello, 2022, p. 233):

The first group contains those who have actively taken part in air strikes, either through direct attack (the UK, France, Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands), or by providing air support or reconnaissance (Germany, Italy and Poland).

The second group of countries is made up of those whose contribution is directed towards training and education of local forces, mostly at the Kurdish Training Coordination Center (KTCC) in Erbil, but also at other locations[9]. These training missions were small, although some countries deployed significant contingents (between 30 and 500), including Spain, Hungary, Finland, Sweden, Romania and Portugal.

Last, making up a third group are the countries whose only material contribution has been logistics (overflights, such as Greece and Cyprus), or simply expressions of political support (Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Luxembourg and Slovakia).

From the above, Romania, Portugal, Hungary, Greece and Cyprus, each contributing to training and logistics, have not suffered attacks on their territory. Switzerland, while not taking part in the Coalition against Daesh, has been the target of attacks, and there is a reason why.

Like other European countries in the 1980s and 1990s, Switzerland has been used by jihadist militants- mostly from North Africa- as a logistical base to raise funds, spread propaganda and provide support to jihadist organisations. Until 2001, jihadist networks were largely able to operate in the country with just a few arrests and deportations. However, 9/11 changed the Swiss approach to terrorism. In 2009, 2010 and 2011, there were several cases linked to Al-Qaeda operating from Swiss soil, providing either logistical support or issuing propaganda (Hofer, 2020, p. 20).

Therefore, aside from the military contribution of each country, the presence of jihadist recruitment networks that have favoured or facilitated the journey to the conflict zone is also crucial. In the case of France, three cases of networks that are said to have facilitated logistics and travel to conflict zones will be cited here: (1) 'Rachid', 'Nasser' and 'Said': Jihad facilitators in France, 1992 to 1994; (2) Abu Turab' and 'Tarek', who mobilised recruits to Fallujah: Iraq 2003 to 2004; (3) the Syrian war via Skype: enablers move to the Web, 2013 to 2014 (Holman, 2016, p. 13).

For its part, the Abu Walaa network in Germany was responsible for the Christmas market attack in Berlin in December 2016, which resulted in the death of 12 people and 56 injured (Bin Sudiman, 2017, p. 10). This attack on German soil was the first Daesh-linked fatal attack in Germany by a Tunisian national, Arnis Amri, linked to the Abu Walaa network. (Heil, 2017, p g. 1). Also in Germany, the Tajik network would attempt to attack a NATO base, with Daesh officials directing the cell's activities from Afghanistan and Syria. (Soliev, 2021).

The UK can be cited as the origin of the main platform for Daesh in Europe, where a network grew that would spread across Europe, based on a movement that initially supported Al-Qaeda and mobilised a generation of jihadists in the 2000s. After being banned, this network reappeared under the name Islam4UK, under the leadership of the radical British Pakistani preacher Anjem Choudary. This network was replicated in Belgium (Sharia4Belgium), the Netherlands (Sharia4Holland), Spain (Sharia4Spain) Denmark (Sharia4Denmark), Finland (Sharia4Finland), Italy (Sharia4Italy), France (Sharia4France, Forsane Alizza), Germany (Millatu Ibrahim) and Norway (The Prophet's Umma) (Nesser, 2019, p. 18).

Belgium is prolific when it comes to recruitment networks, and according to Ostaeyen (2016, p. 7), the ones that have been most active and have managed to send hundreds of radicals to the battlefields of Iraq and Syria are Sharia4Belgium, Resto Tawhid (Jean-Louis Denis), and the so-called Zerkani network.

There are large Muslim communities in the northern regions of Italy, including Lombardia, Veneto and Emilia Romagna, where most cases of radicalisation are found, although there are individuals and networks in other regions of the country, too. Jihadists do not usually live in metropolitan areas, but in small towns and other rural regions. Some of these radicals come from seemingly stable families, others have a troubled past and comprehensive criminal records, and others are radicalised from established jihadist networks (Vidino and Marone, 2017, p. 5).

In this dynamic, Marone (2017, p. 51-55) points to four families that "produced" foreign fighters: the Sergio-Kobuzi family, the Brignoli-Koraichi family, Bencharki-Moutaharrik and Abderrahmane Khachia, and Pil -Sagrari.

In Austria, authorities were able to link Kujtim Fejzulai - responsible for the 2020 Vienna attack - to 21 individuals, and 12 individuals were arrested in this regard. Police in Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Turkey also arrested other people linked to the terrorist. A considerable number of them shared the same ethnicity, with family roots in the Balkans, especially in countries[10] with an Albanian population (Saal and Lippe, 2021, p. 36).

In the case of the attack in Barcelona on 17 August 2017, Garc a Calvo and Reinares (2022, p. 3) explain how an imam named Es Satty acted as a radicaliser of 10 terrorists (9 of them teenagers and second generation, raised or born in Ripoll, descendants of Moroccan immigrants), leading them to violence, and how important the links[11] of kinship and friendship were in the creation of this jihadist cell.

Table 4 shows how all countries in the EU that suffered attacks in the period 2014-2023 (including the UK) produced foreign fighters who went to fight in Iraq and Syria. The 13 countries in Table 4 therefore meet one or both of the conditions set out by Nesser (2019), namely: (1) having maintained a policy of intervention in armed conflicts against Daesh, and/or (2) having domestic and/or international jihadist networks on national territory, the same ones that could have helped the displacement of their foreign fighters.

Table 4

Foreign fighters and the military contribution of EU countries that have suffered attacks

Note: Elaboration based on Soufan Group (2017, p. 12, 13),

Global Coalition (2018)and Mello (2022)

3. INTENTIONALITY

In the previous section, we analysed the ability to attack factor of the concept of threat. In this section, we will look at intentionality. Intentionality has been defined as the conscious will to do harm (Couto, 1980, p. 329). Who are the individuals who will do harm by virtue of their extremist beliefs?

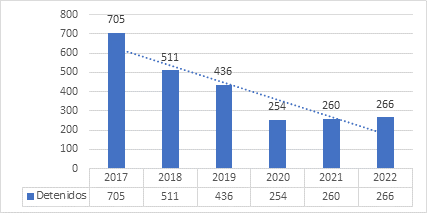

3.1. THE DATA: ARRESTS AND SUSPECTED RADICALISATION

The lists of radicals/extremists held by each member state of the EU are confidential or secret. These records include the situation of each individual, how dangerous they are, the level of need for monitoring and, where necessary, the requests for additional measures.

Nonetheless, open sources provide some references[12] to official figures of individuals considered extremists, as well as estimates made by independent researchers, which allow us to infer some numbers that can be used to assess the terrorist threat.

The mobilisation of the jihadist ranks during the Syrian war has contributed significantly to the growth of the extremist pool in Europe. Paul and Acheson (2019, as cited in the German Federal Ministry of the Interior, n.d.) explain how the number of jihadist extremists in Germany in 2019 was estimated at 26,560, of whom 2,240 would be radical jihadists. The number of extremists was to grow significantly in Germany: 9,700 in 2016, 10,080 in 2017, and 11,300 in 2018. In addition, a number of investigations to this effect are ongoing, with 1,300 suspects linked to jihadist terrorism on German soil (p. 46).

For the UK, estimates have pointed to as many as 25,000 jihadist extremists, of whom 3,000 have been considered a serious threat at some point, with 500 under permanent surveillance. France, for its part, had 20,000 extremists on the February 2018 list of radicals and, of those, 4,000 are monitored as a potential serious threat (Nesser, 2019, p. 19, 20).

Swedish authorities monitored 2,000 subjects identified as potential threats to national security in 2017. Indeed, the then head of the Swedish Security Service, Klas Friberg, noted that in 2019, there were 3,000 individuals in Sweden with the potential to carry out attacks (Paul and Acheson, 2019, p. 88, as cited in the Swedish Security Service [SAPO], 2017).

As for people who have decided to take the "leap" into action, going to conflict zones as foreign fighters, the numbers speak for themselves (Soufan Group [GS], 2017): (1) More than 42,000 foreign fighters travelled to join Daesh from more than 120 countries between 2011 and 2016. (2) Of this number, an estimated 5,000+ were from Europe, mostly Belgium, Germany and the UK, but with significant numbers from Austria, Denmark, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and Spain.

Relevant in this respect is the reasoning of Leuprecht et al (2010), who argue that there is a big gap between belief and action. These authors highlight the contrast between security reports and investigations in the UK, where out of a population of 1 million people, only 50,000 would accept the justification for committing terrorist attacks, and only 200 have been arrested for active participation in terrorist activities (p. 47).

In this regard, Figure 4, showing jihadist arrests in the period 2017-2022 in the EU, illustrates that as the number of attacks has fallen as a result of police pressure, network monitoring and tracking, the number of arrests has likewise fallen. What this indicates, however, is that radicals' leap into action from the world of ideas has been diminished by police action, not by waning intentionality.

Figure 4.

Jihadist

arrests in the European Union 2017-2022

Note: Elaborated from EUROPOL (2017, 2022, 2023)

When viewed through the lens of the Leupechet et al. argument, the above open source examples - which do not contain the confidential lists held by each country - together with the actual numbers of European foreign fighters (Table 4) and those detained in Europe (Figure 4), give an idea of the thousands of jihadist extremists radicalised in ideas and potential perpetrators of attacks in Europe.

3.2. THE CYCLE OF HATE

A terrorist attack provokes an extreme reaction against the entire Muslim community, which in turn leads to vulnerable elements of society being attracted by jihadist siren songs, seeing themselves as likewise legitimised, and presenting themselves as victims and defenders of their community. Such is the xenophobia-recruitment-attack cycle that feeds back on itself, and which Guo warned (2015) of: the cycle of hatred.

Ramos (2020, p. 53) explains this clever Daesh strategy: the group attempts to confront Europeans, creating a climate of suspicion and provoking strong anti-Muslim sentiment, polarising societies.

This dynamic of hatred flushes in so-called "parallel societies", where a set of social and cultural disadvantages converge, transforming them into places where radicalisation can flourish. As Sanz (2018, p. 268) explains, the social organisation of a community or group that presents a certain homogeneity of immigrants, who, disenchanted with the host country, do not accept its rules, adopts a system of values and principles close to their ethno-cultural environment.

Most of the perpetrators of attacks in Europe have been nationals, but two of the terrorists in the Paris attacks in November 2015 carried Syrian passports. Despite one of the documents being a fake, the fingerprints and photos matched those taken in October 2015 at a refugee centre in Greece (Funk and Parkes, 2016, p. 1).

Why would a terrorist carry a passport on a suicide mission? Charlie Winter, a renowned jihadist analyst, puts forward his reasoning: "Why would a jihadist who expressly rejects all aspects of modern citizenship carry a passport to a suicide mission? So that it can be found" (Kingsley, 2015).

In this regard, Funk and Parks (2016, p. 2) note how Daesh may have had a larger political objective for using refugee routes: to provoke social and political reactions, beyond killing Westerners or taking out strategic targets. To trigger fear of Muslim refugees among Europeans. If the Paris attacks were indeed carried out by registered refugees, Daesh's objective had already been achieved, mere suspicion alone having succeeded in provoking social division.

Martin Ramirez (2017) states that no nations of peoples is violent, made up of drug traffickers and criminals, because what some fundamentalists, criminals or madmen may do cannot be blamed on any one group. Fundamentalist, violent or confused individuals can be found everywhere, in all societies and religions, strengthening intolerance, feeding on xenophobia and hatred. There is no such thing as Islamic terrorism, just as there is no such thing as Christian or Jewish terrorism (p. 219).

Criminal law holds that what is important is the attitude of the person, i.e. the intent or recklessness involved in committing a crime. It does not matter what an individual believes, where they belong, or what faith they profess. No one is exempt from scrutiny on the crimes commission, since the inspection exercised by the state is for the safety of all citizens.

3.3. JIHADIST RADICALISATION: KALEIDOSCOPE OF FACTORS

Qualitative research conducted on the motives that lead to violent extremism, based mainly on interviews, suggests two main categories, the so-called push and pull factors. First, we will examine the push factors, i.e. the conditions that lead to violence and the structural environment in which violence emerges. Then we will look at the pull factors, i.e. individual motivations and processes that play a crucial role in transforming ideas and grievances that lead to violent extremism (United Nations General Assembly [UNGA], 2015, p. 7).

The mechanisms of radicalisation are a product of the interaction of these factors, with different speeds of radicalisation. There is no single cause that leads to extremism, but a kaleidoscope of elements and numerous individual combinations (RAN, 2016, p. 1, 3, 4) from which we can construct an overview of social dynamics and mobilisation to terrorism. These factors have proven useful for a better understanding of extremism (Schmid and Tinnes, 2015, p. 37).

One of the most ambitious and comprehensive studies on the subject is the 2019 TRIVALENT (Terrorism pReventIon Via rAdicaLisation) project, sponsored by the European Commission. This research identifies the main causes of violent extremism, which are found at the meso level - social interaction, radical rhetoric and group identity - at the micro level - political grievances, the search for meaning and deprivation - and at the macro level - foreign policy (Moccia, 2019, pp. 3, 24).

The IMPACT Europe project (Innovative Method and Procedure to Assess Counter-violent-radicalisation Techniques in Europe) identifies a number of factors, such as ideology and interpretation of religion, and social exclusion, as the most significant factors reported by the scientific literature in relation to terrorism (Hemert, Berg, Vliet, Roelofs, & Veld, 2014, p. 28).

While the causes are many and varied, one issue is of a fundamental nature: ideology. It is ideology that makes the survival of terrorist groups possible (Habeck, et al, 2015, pp. 10, 11), in line with Dunford's argument, when he notes that "it is the flow of foreign fighters, along with the ability to mobilise resources and ideology, that enables terrorist organisations to function (The Defence Post [TDP], 2018).

Moghadam (2008) explains how jihadism is presented through their ideology as a kind of justification for extremists: (1) it attempts to create an awareness among Muslims that their faith is in military, economic, political, religious and cultural decline, compared to the golden age of the early years of its existence; (2) it identifies the Crusaders, Zionists and apostates, a kind of anti-Muslim coalition, as the source of Muslims' ills and their disgrace and humiliation; (3) it creates an identity among its followers and acolytes, providing a sense of belonging and definition as part of a supranational entity, the Muslim community; (4) last, it provides a plan of action, jihad, that will change history and bring about the redemption they deserve, presenting martyrdom as the supreme way of doing jihad (p. 2).

A popular leitmotif among Daesh followers - believed to be the work of journalist Abdulelah Haider Shaye - illustrates the essential role of the jihadist ideology: "The Islamic State was designed by Sayyid Qutb, taught by Abdullah Azzam, globalised by Osama Bin Laden, made real by Abu Musab al-Zarquwi, and implemented by the al-Baghdadis, Abu Omar and Abu Bakr"(Hassan, 2016, p. 19).

The mantra of al-Bahgdadi's Daesh drew a historical parallel between the Crusaders' occupation of the Holy Land in ancient times and today by their contemporary proxies, led by the US. From here the demonisation of the West, which became a crusader (Elorza, 2020, p. 20).

To justify violence against believers in Islam, jihadists use Takfir, i.e. they label other Muslims as kafir (non-believers or apostates), infidels, thereby legitimising the use of violence against them (Kadivar, 2020, p. 1, 3). This term reveals an important point: Daesh is an enemy of Christians, Jews and even Muslims, i.e. anyone who does not have the group's extremist view of the world.

Indeed, year after year Muslims themselves are Daesh's first targets and its biggest victims, in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. Table 5 shows that, in 2023, most of the victim countries are majority or exclusively Muslim. According to Igualada and Aguilera (2024), the number of jihadist attacks worldwide in 2023 was 2,304, causing 9,572 casualties (pp. 17, 32).

Although not dismantled, the core of the Daesh structure in Iraq, once the centre of jihadist activity, currently has limited capacity to carry out high-impact actions, with West Africa now becoming the epicentre of jihadist violence (Igualada and Aguilera, 2024, p. 33).

Table 5.

|

Number of jihadist terrorism victims by country 2023

Note: Igualada and Aguilera (2024, p. 32)

As already stated, radicalisation is a combination of push and pull factors, which in a non-deterministic way can affect individuals and lead them to radicalisation. That said, the importance in this kaleidoscope of jihadist ideology cannot be underestimated because, according to the Soufan Group (2017), in its name more than 5,000 Europeans have left their lives behind to join Daesh in Syria and Iraq (p. 11), and in its name, attacks are carried out every year in Europe and other parts of the world.

3.4. THE EXTERNAL THREAT: ISIS-K

According to the report[13] sent to the US Congress by the Inspector General of Operation Inherent Resolve, senior Daesh leaders in Iraq and Syria remain committed to enabling attacks abroad. The group's affiliates continue to attack regional targets, most notably ISIS-K, based in Afghanistan (Storch, Lewis, and Martin, 2024, p. 11).

In fact, ISIS-K is undergoing a shift from a regional to a more global approach by implementing a two-pronged strategy. (Zelin, 2023):

Through its al-Azaim Media Foundation, ISIS-K has developed an independent media structure, which produces content in Arabic, English, Farsi, Pashto and other languages and dialects, with content referring to foreign targets from India, Iran and Pakistan to Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, China, Europe, Russia and the US.

The second part consists of planning and executing attacks abroad, whether guided, directed or inspired.

When looking at the scope of international attacks in recent times, ISIS-K has been prolific:

In early January 2024, on its Telegram channels, Daesh (ISIS_K) claimed responsibility for the attack in Iran by individuals who blew themselves up with explosive belts, killing nearly a hundred people. The attack took place during the fourth anniversary memorial for General Qassem Soleimani[14], who was killed by a US drone, in the Iranian city of Kerman (Hafezi, Elwelly, and Tanios, 2024).

On 28 January 2024, hooded assailants attacked a Catholic church in Istanbul, killing one person. Shortly afterwards, through its news agency Amaq News, Daesh (ISIS_K) claimed responsibility for the attack. This attack drew attention to the growing presence of Daesh's Afghan branch, ISIS-K, in Turkey. (Shahbazov, 2024)

The attack on the Crocus concert hall in Krasnogorsk (Russia) on 22 March 2024, which killed 139 people, was the work of ISIS-K. (Strachota, 2024)

Each of these attacks reflects the group's ideological priorities: Iran is a Shia state[15], all the countries attacked have been involved in fighting Daesh in Syria or Afghanistan and/or on their own territory, and all are considered apostates or heretical enemies of the Caliphate. (Strachota, 2024).

Jihadist terrorism specialist Colin Clarke (2023) points out how the international community is failing to adequately assess the threat posed by ISIS-K, which has a presence in almost all of Afghanistan's 34 provinces and a force of between 1,500 and 2,200 men. Since August 2021, ISIS-K has committed more than 400 attacks on Afghan soil. In September 2022, it sent suicide jihadists to the Russian embassy in Kabul and attacked the Pakistani embassy in December, as well as the Kabul Longan hotel, which is frequented by Chinese businesspeople.

In addition, law enforcement agencies in several countries have foiled various terrorist plots in India (3), Iran (4), Germany (3), the Maldives (1), Qatar (1) and Turkey (3). In addition to arrests for links to terrorist plots, on various occasions in several countries, including Britain (2), India (2), Turkey (1), Pakistan (1), and the United States (2), authorities have arrested members linked to ISIS-K for recruitment and fundraising. (Zelin, 2023).

Several ISIS-K plots to attack NATO bases in Germany were broken up in April 2020 by German security forces (Soliev, 2021, p. 30). A number of individuals were arrested in the summer of 2023 in Iran, and others in July, August and December 2023 in Germany, in connection with the preparation of an attack in Cologne. In March 2024, several arrests were made in connection with a plot to attack a synagogue in Moscow on the eve of 22 March. In Turkey, since June 2023, more than 692 individuals linked to ISIS-K have been detained, including 40 individuals linked to the attack in Krasnogorsk in March 2024. (Strachota, 2024)

France foiled several terrorist plots targeting the 2024 Paris Olympics. One such conspiracy was an attack planned on a football match to take place in the city of Saint- tienne, and the perpetrator was in contact with ISIS-K (Clarke and Webber, 2024).

Similarly, two Afghan nationals accused of preparing a shooting attack near the Swedish Parliament were arrested in March this year in Germany (Stern, Pleitgen, and Nicholls, 2024). According to German prosecutors, in the summer of 2023, ISIS-K allegedly ordered the main defendant "to carry out an attack in Europe in reaction to the Koran burnings that were taking place in Sweden and other Scandinavian countries". (DW, 2024)

Although attacks in Europe of a complex nature such as those that took place in Paris in November 2015, led and coordinated by Daesh, had all but been neutralised since the group was defeated and stripped of all territorial control in Syria and Iraq, it appears that ISIS-K once again has the capability to carry out attacks internationally.

In other words, there is a real and serious threat to Europe, the West and all those countries considered apostates according to the jihadist ideology of Daesh.

3.5. ANALYSIS OF RESULTS

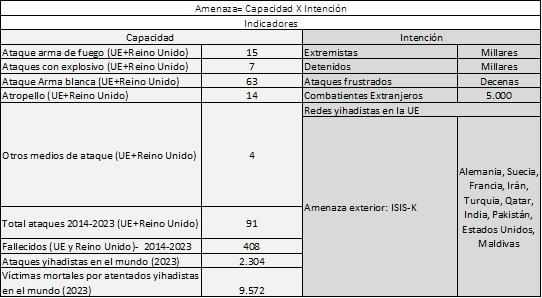

Having overviewed the figures and information on the indicators corresponding to the two variables that make up the concept of threat- capacity and intention- we can now analyse the results, using the summarised data in Table 6, which brings together the figures in Tables 1, 4, 5 and Figures 1, 2, 3, 4.

We agree with Sampieri et al. (2014), when they state that the results of qualitative research should not be generalised, as this is not its purpose, but rather that part of the results or the main ideas derived can be applied to other contexts. As the author of this article, my only aim is to give my own perspective on where and how the results can fit into the field of knowledge of the analysed problem (p. 458).

Table 6

Summary of indicators of the jihadist threat concept

Note: Prepared by the authors, based on the data[16] of Igualada and Aguilera (2024, p. 32, 53-55), Soufan Group (2017, pp. 12, 13), Zelin (2023), DW (2024), Clarke and Webber, (2024), Strachota (2024) and EUROPOL (2017, 2022, 2023).

We began this study by questioning the level of threat in the EU, given that the number of materialised attacks in recent years may seem low. Throughout this work, we have managed to verify that although recent attacks in Europe have been relatively few in number, there is intentionality on the part of both the perpetrators of the attacks and the ideologically radicalised individuals who may make the effective leap to violence, of which there are thousands. The figures for jihadist attacks around the world - which amounted to 2,304 in 2024, with 9,572 fatalities - are an indication of the strength and mobilisation that jihadist ideology is capable of generating at a global level. The military and territorial strength of the group can be taken away, but as long as the ideology that is capable of radicalising and recruiting followers and fighters is not, the threat will remain.

Some may think that what happens abroad is not a European problem, but it does have repercussions in Europe: the thousands of European foreign fighters prove that. Some may think that having ended Daesh's territorial dominance, which is what allowed it to lead/coordinate attacks in Europe, the group has no capacity to attack abroad. The presence of ISIS-K and its terrorist activities in Germany, Sweden and France prove otherwise. And we cannot forget the Daesh-inspired attacks, the lone actors who, wielding a knife or driving a vehicle, can and do kill in the name of the organisation.

The summary figures for the various indicators in Table 6 speak for themselves: hundreds of deaths, dozens of attacks thwarted and hundreds executed, thousands of extremists and detainees in the EU, and thousands of attacks and fatalities worldwide. We can therefore affirm that the jihadist threat in the EU remains high.

4. CONCLUSIONS

This analysis, carried out to answer the question "Is the terrorist threat in Europe low?", focuses on the concept of threat, that is, on the product of the capacity to attack, which includes the conscious will to do harm and intentionality.

The Daesh terrorist group's ability to attack in the EU has evolved from complex, group attacks with weapons and/or explosives to attacks committed by individual actors, without direction or coordination, inspired by their ideology and narrative, and committed with rudimentary tools, bladed weapons or vehicles to cause mass deaths.

Legislation passed within the EU, international cooperation and the police response have helped disrupt numerous plots and made it more difficult for terrorists to gain access to firearms, explosives and other more lethal weapons. In other words, the ability to carry out attacks has been undermined by police action.

In terms of intentionality, the number of radicals in the field of ideas, with extremist world views and faithful to the jihadist ideology, is in the order of thousands. The data on foreign fighters and detainees already indicate the proportion of those who have made the leap to armed action, i.e. to being capable of perpetrating violence.

Given the above, and despite the diminished capacity to carry out attacks, the intentionality that drives individuals to radicalise - as identified in the number of attacks, foiled plots, foreign fighters and extremists present in the EU - remains high, and with it does the threat.

Of great academic and practical interest to governments is why there have been attacks in 13 countries in Europe (including the EU and the UK) and none in others. The presence of social and economic circumstances, among others, among vulnerable populations, coupled with the presence of jihadist networks, which through personal contact have facilitated radicalisation and travel to conflict zones, partly explain this. Countries military action against Daesh, through participation in the Global Coalition against the group, put these states in the crosshairs of the terrorist organisation. According to the analysis carried out, the presence of one or both of these two factors is a determining factor in the commission of attacks in that country by Daesh or its supporters.

Outside the EU, attacks on Russia, Iran and Turkey by ISIS-K confirm this, in line with the group's ideological priorities: Iran is Shiite, and the other targeted countries, considered heretical enemies of the Caliphate, have been involved in fighting Daesh in Syria or Afghanistan and/or on their own territory.

Add to this the ability to attack of Daesh's Afghan affiliate, ISIS-K- which can be identified by analysing attacks in Iran, Turkey and Russia, as well as foiled plots in Germany, France, Sweden, India, the Maldives and Qatar- and we have a real and serious threat, not only to the EU, but to all countries, be they Christian, Muslim or Jewish, that oppose the jihadist creed and are considered apostates by the group.

The possible causes (push and pull factors) that lead to jihadism, including terrorist ideology, verify that certain countries with jihadist networks on their territory are more susceptible to attacks than others. Therefore, in addition to working to neutralise the capacity to carry out attacks, we must work to thwart the cycle of hatred and to neutralise the ideology's capacity for recruitment and attraction. Daesh understands no faith but its own, and considers itself the true defender of Islam, while the rest of the world, be they Christians, Jews or Muslims, are apostates and enemies.

The cycle of hatred is powerful, and it is easy to fall into. No one should be judged for belonging to a certain ethnicity or religion, but they should for their willingness to commit crimes and harm others. No one is above the law and people are judged by their actions, not their beliefs, with the state exercising its functions over all citizens to ensure their safety.

It is therefore a struggle between those who respect the values and attitudes that allow for coexistence between people of different cultures and religions - including Muslims, Christians and Jews - and the jihadists. The enemy is the violent extremist, the rest must learn to live in peace and follow the laws and principles that make coexistence and security possible.

5. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

AGNU. (2015, December 24). Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism. Report of the Secretary-General. Seventieth session. Agenda items 16 and 117. Retrieved from United Nationes: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n15/456/16/pdf/n1545616.pdf

Bakkour, S., & Stansfield, G. (2023). The Significance of ISIS's State Building in Syria. Midde East Policy. Volume 30. Issue 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/mepo.12681, 126-145.

BBC. (2019b, december 20). Australian brothers guilty of IS plane bomb plot. Retrieved from BBC: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-49764450

Bin Sudiman, S. A. (2017). Attacks in Europe: A New Strategy to Influence Hijra to IS Distant Wilayats? Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses , Vol. 9, No. 2 (February 2017), 10-13.

Calvo, J. L. (2016). Military Response: Strategies to Defeat Daesh and Regional Restabilization. Strategy Notebook 180. Instituto Espa ol de Estudios Estrat gicos, 180. Retrieved from http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/cuadernos/CE_180.pdf

Clarke, C. P. (2023, April 29). Islamic State Khorasan Province Is a Growing Threat in Afghanistan and Beyond. Retrieved from The Diplomat: https://thediplomat.com/2023/04/islamic-state-khorasan-province-is-a-growing-threat-in-afghanistan-and-beyond/

Clarke, C., & Webber, L. (2024, August 1). ISIS-K Goes Global. Retrieved from Foreign Affairs: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/afghanistan/isis-k-goes-global

Comisi n Europea. (2020, December 9). A Counter-Terrorism Agenda for the EU: Anticipate, Prevent, Protect, Respond. Retrieved from COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS A Counter-Terrorism Agenda for the EU: Anticipate, Prevent, Protect, Respond: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0795

Correia, J., & Santamaria, J. (2021). Propaganda do Terror: Amea as para a Seguran a da Uni o Europeia. Revista de Ci ncias Militares - Vol. IX, N. 1. Maio, 209-241.

Couto, A. C. (1980). Elementos de Estrat gia- Apontamentos para um curso. Lisboa: IAEM.

Duarte, F. (2017). Os Objectivos Estrat gicos do DAESH na Europa. Janus, 18-19. Retrieved maio 20, 2019, from http://janusonline.pt/images/anuario2017/1.5_FelipePDuarte_DAESH.pdf

DW. (2024, August 21). Germany charges 'IS' supporters with Sweden attack plot. Retrieved from DW: https://www.dw.com/en/germany-charges-is-supporters-with-sweden-attack-plot/a-70009697

Elorza, A. (2020). EL C RCULO DE LA YIHAD GLOBAL. DE LOS OR GENES AL ESTADO ISL MICO. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Escorrega, L. C. (2009). A seguran a e os "novos" riscos e amea as: perspectivas v rias. Revista Militar, Agosto/Setembro(2491-2192). Retrieved Janeiro 7, 2019, from https://www.revistamilitar.pt/artigo/499

Europol. (2017, June 15). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2017. Retrieved from https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/main-reports/eu-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-te-sat-2017

Europol. (2019, June 27). Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2019. Retrieved from https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/main-reports/terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2019-te-sat

Europol. (2020a, June 23). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report (TE-SAT) 2020. Retrieved from https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/main-reports/european-union-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-te-sat-2020

Europol. (2021, June 22). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report 2021 (TE-SAT). Retrieved from https://www.europol.europa.eu/publication-events/main-reports/european-union-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2021-te-sat

Europol. (2022, July 13). European Union Terrorism Situation & Trend Report (TE-SAT) 2022. Retrieved from https://www.europol.europa.eu/publication-events/main-reports/european-union-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2022-te-sat

Europol. (2023, June 14). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report 2023 (TE-SAT). Retrieved from https://www.europol.europa.eu/publication-events/main-reports/european-union-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2023-te-sat

Flade, F. (2018). The June 2018 Cologne Ricin Plot: A new Threshold in Jihadi Bioterror. CTCSentinel, 11(7), 1-3. Retrieved maio 20, 2019, from https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2019/01/CTC-SENTINEL-082018-final.pdf

Funk, M., & Parkes, R. (2016). Refugees versus terrorists. European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS), 1-2.

Garc a-Calvo, C., & Reinares, F. (2022, August 3). Atentados en Barcelona y Cambrils: (I) formaci n de la c lula de Ripoll, radicalizaci n de sus miembros y preparaci n de unos actos de terrorismo a gran escala. Retrieved from https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/documento-de-trabajo/atentados-en-barcelona-y-cambrils-parte1-formacion-de-la-celula-de-ripoll-radicalizacion-de-sus-miembros-y-preparacion-de-unos-actos-de-terrorismo-a-gran-escala/

Global Coalition. (2018, 1 March). Norway to continue military contribution to the fight against Daesh. Retrieved from Global Coalition: https://theglobalcoalition.org/en/norway-continue-military-contribution-against-daesh/

Global Coalition. (2024). Norway s contribution towards the Global Coalition against Daesh. Retrieved from Global Coalition: https://theglobalcoalition.org/en/partner/norway/

Guo, J. (2015). Hating Muslims plays right into the Islamic State s hands. Washington Post. Retrieved Dezembro 11, 2018, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/11/17/isis-wants-you-to-hate-muslims/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.3cdbb0d8c155

HABECK, M., DONNELLY, J. C., HOFFMAN, B., JONES, S., KAGAN, F. W., KAGAN, K., . . . ZIMMERMAN, K. (2015, December 1). A Global Strategy for Combating al Qaeda and the Islamic State. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep03231

Hafezi, P., Elwelly, E., & Tanios, C. (2024, January 4). Islamic State claims responsibility for deadly Iran attack, Tehran vows revenge. Retrieved from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-vows-revenge-after-biggest-attack-since-1979-revolution-2024-01-04/

Hamming, T. R. (2023). The General Directorate of Provinces: Managing the Islamic State s Global Network. CTC Sentinel. July, 20-27.

Hassan, H. (2016, June 13). The Sectarianism of the Islamic State: Ideological Roots and Political Context. Retrieved from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/06/13/sectarianism-of-islamic-state-ideological-roots-and-political-context-pub-63746

Heil, G. (2017). The Berlin Attack and the Abu Walaa Islamic State Recruitment Network. CTC Sentinel. February 2017. Vol 10, issue 2, 1-11.

Hemert, D. v., Berg, H. v., Vliet, T. v., Roelofs, M., & Veld, M. H. (2014, November 12). Innovative Method and Procedure to Assess Counter-violent-radicalisation Techniques in Europe. Synthesis report on the state-of-the-art in evaluating the effectiveness of counter-violent extremism interventions. Retrieved from http://impacteurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/D2.2-Synthesis-Report.pdf

Hofer, M. (2020, October). IRI Report: Switzerland. Retrieved from International Institute of Counter Terrorism (ICT): https://www.ict.org.il/images/Switzerland_IRI.pdf

Holman, T. (2016). Gonna Get Myself Connected :The Role of Facilitation in Foreign Fighter Mobilizations. Perspectives on terrorism. April, 2-23.

Igualada, C., & Aguilera, A. (2024, March 25). Anuario del terrorismo yihadista 2023. Retrieved from Observatorio Internacional de Estudios sobre Terrorismo (OIET): https://observatorioterrorismo.com/actividades/anuario-del-terrorismo-yihadista-2023/

Kadivar, J. (2020a). Exploring Takfir, Its Origins and Contemporary Use: The Case of Takfiri Approach in Daesh s Media. Contemporary Review of the Middle East, , vol. 7(3), 259-285.

Kingsley, P. (2015, November 15). Why Syrian refugee passport found at Paris attack scene must be treated with caution. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/15/why-syrian-refugee-passport-found-at-paris-attack-scene-must-be-treated-with-caution

Leuprecht, C., Hataley, T., Moskalenko, S., & Mccauley, C. (2010). Containing the Narrative: Strategy and Tactics in Countering the Storyline of Global Jihad. Journal of Policing Intelligence and Counter Terrorism. April , 42-57.

Magri, P. (2016). In A. Varvelli, Jihadist hotbeds. Understanding local radicalization processes (pp. 9-14). Mil n: ISPI.

Marone, F. (2017). Ties that Bind: Dynamics of Group Radicalisation in Italy s Jihadists Headed for Syria and Iraq . THE INTERNATIONAL SPECTATOR, L. 52, NO. 3, , 48-63.

Mart n Ramirez, J. (2017). Terrorismo yihadista e Islam . In C. Pay Santos, El terrorismo como desaf o a la seguridad . Pamplona: Aranzadi.

Mello, P. (2022). Incentives and constraints: a configurational account of European involvement in the anti-Daesh coalition. European Political Science Review. 14(2), 226-244. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-political-science-review/article/incentives-and-constraints-a-configurational-account-of-european-involvement-in-the-antidaesh-coalition/8FEB909EA744514EC01E88649A4E0A87

Merrill, J. (2018, mar o 15). Seven years of death from the air: Who's bombing whom in Syria. Middle East Eye. Retrieved junho 1, 2019, from https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/seven-years-death-air-whos-bombing-whom-syria

Moccia, L. (2019). Literature Review on Radicalisation. Retrieved from European Union s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 740934. Proyect TRIVALENT: Terrorism pReventIon Via rAdicaLisation countEr-NarraTive.

Moghadam, A. (2008). The Salafi-Jihad as a Religious Ideology. CTC Sentinel, Vol 1. Issue 3. 1-3.

Nesser, P. (2018). Europe hasn t won the war on terror. Politico. Retrieved julho 13, 2019, from https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-hasnt-won-the-war-on-terror/

Nesser, P. (2019). Military Interventions, Jihadi Networks, and Terrorist Entrepreneurs: How the Islamic State Terror Wave Rose So High in Europe. CTC Sentinel. March, 15-21.

Nesser, P. (2021). Foiled Versus Launched Terror Plots: Some Lessons Learned. In EICTP, KEY DETERMINANTS OF TRANSNATIONAL TERRORISM IN THE ERA OF COVID-19 AND BEYOND. TRAJECTORY, DISRUPTION AND THE WAY FORWARD. Vol II (pp. 143-158). Vienna: European Institute for Counter Terrorism and Conflict Prevention (EICTP). Citypress GmbH.

Nesser, P. (2023, february 21). Introducing the Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED). Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00223433221123360#:~:text=research%20and%20policy.-,Introduction,are%20prevented%20(foiled%20plots).

Osborne, S. (2018, mar o 23). Does Isis really 'claim every terror attack'? How do we know if a claim is true? Independent. Retrieved mar o 28, 2018, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-terror-attack-claim-real-true-legitimate-fake-false-how-to-know-a8270116.html#explainer-question-0

Ostaeyen, P. V. (2016). Belgian Radical Networks and the Road to the Brussels Atacks. CTC Sentinel. June, 7-12.

Paul, A., & Acheson, I. (2019). Guns and glory: Criminality, imprisonment and jihadist extremism in Europe. Retrieved from https://www.epc.eu/content/PDF/2019/CrimeTerror_full_version.pdf

Perliger, A., & Milton, D. (2016, November 11). From Cradle to Grave: The Lifecycle of Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria. Retrieved from Combating Terrorism Center at West Point: https://ctc.westpoint.edu/from-cradle-to-grave-the-lifecycle-of-foreign-fighters-in-iraq-and-syria/

POOLRE. (2017, January-July). Pool Re Terrorism Threat & Mitigation Report January - July 2017. Londres: Pool Re s Terrorism Research and Analysis Centre. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/pool-re-terrorism-threat-mitigation-report-january-july-scrimgeour

Ramos, J. M. (2019). El planeamiento de seguridad en Grandes Eventos: El factor Soft Target y la amenaza terrorista low cost. Cuadernos de la Guardia Civil. Revista de seguridad p blica. N m. 59, 143-175.

Ramos, J. M. (2020). Propaganda do terror: amea as para a seguran a da Uni o Europeia. Mestrado em Ci ncias Militares. Seguran a e Defesa. Instituto Universit rio de Ci ncias Militares.

RAN. (2016, January 4). The Root Causes of Violent Extremism. Retrieved from https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/pages/page/root-causes-violent-extremism-04-january-2016_en

Reinares, F., Garc a-Calvo, C., & Vicente, . (2017, August 9). Dos factores que explican la radicalizaci n yihadista en Espa a. Retrieved from https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/analisis/dos-factores-que-explican-la-radicalizacion-yihadista-en-espana/

Rodr guez, M. (2017, August 20). Una c lula yihadista integrada por hermanos y amigos. Retrieved from El Pais: https://elpais.com/ccaa/2017/08/20/catalunya/1503257642_106241.html

Rojas, A., & Carri n, F. (2017, julho 15). El veh culo como 'arma de guerra', una idea de Al Qaeda ya usada en Francia. El Mundo. Retrieved novembro 13, 2017, from www.elmundo.es/internacional/2016/07/15/578829d8e2704e40088b45e7.html

Saal, J., & Lippe, F. (2021). The Network of the November 2020 Vienna Attacker and the Jihadi Threat to Austria. CTC Sentinel. January , 33-43.

Sampieri et al, R. (2014). Metodolog a de la Investigaci n (6 ed.). M xico: McGRAW HILL.

Sanz, N. (2018). Parallel societies as a breeding ground for jihadism. In M. A. Sanchez, I. B. Torre, A. D. G mez, M. G. Barranco, B. G. Sanch z, and N. S. Mulas, El terrorismo en la actualidad: un nuevo enfoque pol tico criminal (pp. 247-282). Valencia: Tirant lo blanch.

Schmid e Tinnes, A. e. (December 2015). Foreign (Terrorist) Fighters with IS: A European Perspective. https://icct.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ICCT-Schmid-Foreign-Terrorist-Fighters-with-IS-A-European-Perspective-December2015.pdf

Swedish Security Service (SAPO), 2017. Report.

GS. (December 2015). Foreign Fighters: An Updated Assessment of the Flow of Foreign Fighters into Syria and Iraq. Retrieved December 20, 2018, from The Soufan Group: http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/TSG_ForeignFightersUpdate3.pdf

GS. (October 2017). Beyond the Caliphate, Foreign Fighters and the Threats of Returnees. Retrieved December 20, 2018, from The Soufan Group: http://thesoufancenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Beyond-the-Caliphate-Foreign-Fighters-and-the-Threat-of-Returnees-TSC-Report-October-2017-v3.pdf

Shahbazov, F. (14 March 2024). What Does a Recent ISIS-K Terror Attack Mean for Turkey? https://www.stimson.org/2024/what-does-a-recent-isis-k-terror-attack-mean-for-turkey/#:~:text=On%20January%2028%2C%202024%2C%20masked,people%2C%20most%20Central%20Asian%20nationals.

Soliev, N. (2021). The April 2020 Islamic State Terror Plot Against U.S. and NATO Military Bases in Germany: The Tajik Connection. CTC Sentinel. January, 30-38.

Soufan, A., and Schoenfeld, D. (2016). Regional Hotbeds as Drivers of Radicalization. In A. Varvelli, Jihadist hotbeds. Understanding local radicalization processes (pp. 15-36). Milan: ISPI.

Stern, C., Pleitgen, F., and Nicholls, C. (22 March 2024). Germany arrests suspected ISIS supporters accused of planning terror attack on Swedish parliament. Retrieved from CNN: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/03/19/europe/germany-isis-suspects-sweden-intl/index.html

Storch, R., Lewis, S., and Martin, P. (1 January-31 March 2024). Lead Inspector General report to the United States Congress. Operation Inherent and other U.S activities related to Iraq and Syria. Retrieved from the United States government: https://www.stateoig.gov/uploads/report/report_pdf_file/oir_q2_mar2024_final_508.pdf

Strachota, K. (29 March 2024). Islamic State-Khorasan: global jihad's new front. Retrieved from Centre for Eastern Studies: https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2024-03-29/islamic-state-khorasan-global-jihads-new-front

TDP. (16 October 2018). Foreign fighters continue to join ISIS in Syria, US Joint Chiefs chair says. Retrieved from The Defense Post: https://www.thedefensepost.com/2018/10/16/isis-foreign-fighters-travel-syria-dunford/

TST. (9 February 2019). ISIS 'caliphate' down to 1% of original size. Retrieved from The Strait Times: https://www.straitstimes.com/world/isis-caliphate-down-to-1-of-original-size

Vidino, L., and Marone, F. (November 2017). The Jihadist Threat in Italy: a Primer. Retrieved from Analysis No. 318. ISPI. stituto per gli studi di politica internazionale: https://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/analisi318_vidino-marone.pdf

WC. (27 October 2017). Reports: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees. Retrieved from Wilson Center: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/reports-foreign-fighters-and-the-threat-returnees

Woo, G. (2017). Understanding the principles of terrorism risk modelling from the attack in Westminster.http://forms2.rms.com/rs/729-DJX-565/images/Terrorism-Principles-Westminster.pdf

Zelin, A. Y. (11 September 2023). ISKP Goes Global: External Operations from Afghanistan. Retrieved from Washington Institute for Near East Policy: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/iskp-goes-global-external-operations-afghanistan