Francesco Dotto

Lieutenant Colonel of Carabinieri

II level Master Degree in “International Cooperation and Security Diplomacy”

Graduate in Law

OLD SOUL AND EUROPEAN REGULATORY FRAMEWORK: THE CODE OF CONDUCT OF GENDARMERIE CORPS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

OLD SOUL AND EUROPEAN REGULATORY FRAMEWORK: THE CODE OF CONDUCT OF GENDARMERIE CORPS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE EUROPEAN REGULATORY FRAMEWORK. 3. THE ETHICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE GENDARMERIE NATIONALE 4. THE ETHICAL FRAMEWORK AND THE ETHICS COMMITTEE OF THE CARABINIERI. 5. THE CODE OF CONDUCT FOR CIVIL GUARD PERSONNEL AND THE TEN GOLDEN RULES FOR THE GRUPO DE ACCION RAPIDA 6. AGILITY AND KAIZEN: A VALUABLE REFERENCE FOR CITIZENS? 7. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS AND PERSPECTIVES. 8. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES.

Resumen: El estudio de los códigos éticos de la Gendarmería Nacional francesa, el Arma de Carabinieri italianos y la Guardia Civil española pone de manifiesto que para ser eficaces es necesario que sean ágiles, es decir, fáciles de utilizar y comprender, para permitir que los valores éticos se aprendan e interioricen, con la posibilidad que se conviertan también en un punto de referencia para el público, incentivado a emular comportamientos éticos y virtuosos. La claridad, la sencillez y la facilidad de uso de los códigos éticos consolidan las buenas prácticas internas y favorecen la difusión de los principios éticos al conjunto de la sociedad, reforzando el vínculo de confianza entre los ciudadanos y las fuerzas del orden.

Abstract: The study of the codes of ethics of French Gendarmerie Nationale, the Italian Arma de Carabinieri and Spanish Guardia Civil shows that to be effective they need to be agile, i.e. easy to use and understand, so that ethical values can be learned and internalised, with the possibility that they also become a point of reference for the public, who are encouraged to emulate ethical and virtuous behaviour. The clarity, simplicity and user-friendliness of codes of ethics consolidate good internal practices and promote the dissemination of ethical principles to society as a whole, strengthening the bond of trust between citizens and law enforcement agencies.

Palabras clave: Ética, código deontológico, códico de conducta, Kaizen, ejemplo.

Keywords: Ethics, code of conduct, code of ethics, gendarmerie corps, Kaizen, example.

ABBREVIATIONS

BOE: Official State Gazette

CPT: European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

CSPL: Committee on Standards in Public Life

GAR: Grupo de Acción Rápida (Rapid Action Group)

GRECO: Groupe d'Etats contre la Corruption

UN: United Nations

PC-PO: Committee of Experts on Police Ethics and Problems of Policing

1. INTRODUCTION

In the past, the state exercised its sovereignty and imperium power through the police. This has changed over time, culminating in the concept that police forces, while maintaining their duty to defend the state and its free institutions, must first and foremost defend, protect and serve citizens.

As Cold War divisions disappeared, the idea began to take root in the European Community that the police forces of all Member States should have a common ethical basis, structured around shared principles. This was subsequently reflected in full in the United Nations with autonomous enactments.

The centuries-old history of the French Gendarmerie ( 1791), the Italian Carabinieri ( 1814) and the Spanish Guardia Civil (1844), steeped in values and tradition, has had to evolve further to adapt its principles to a new binding law that is no longer national, but generated by international treaties and supranational institutions.

Starting with the Common European Framework and through a historical excursus, the national legal sources and ethical principles of the three authorities have been defined.

By means of simple anonymous interviews with officers of the Gendarmerie, Carabinieri and Civil Guard, data has been collected on the actual knowledge of the sources of ethics and the assimilation of the founding values and principles: given the limited sample for the interviews, senior officers with proven experience from international organisations, central bodies of the various institutions and national teaching centres were used.

It has become clear that the instrument for relaying codes of ethics, i.e. the documents containing the principles, must be easy to use so that the values can be fully assimilated by police officers.

Reflecting on the value of the ethics of the gendarmes and their ability to influence citizens at a time when community building and community policing are fundamental elements of everyday service, it can be seen that the quintessential principles of the gendarmes have become the cornerstones of a solid reference model for civil society.

2. THE EUROPEAN REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

The 1970s marked the start of a profound process of democratisation across Europe, which was to continue uninterrupted in the following years: the European Community was enlarged for the first time with the accession of new states, a transition to democracy took place with the overthrow of the Estado Novo in Portugal, the fall of the military regime in Greece and the death of General Franco in Spain, and the first direct elections to the European Parliament were held. The 1980s saw the collapse of communism, with the further enlargement of the European Community and the end of the Cold War.

The democratisation process inevitably affected all aspects of society, including the exercise of state power and the concept of control of the population through the police and armed forces.

The role played by police forces in state power has evolved significantly from securing public order and protecting government interests to prioritising service to citizens. Despite maintaining the same duties to protect the integrity of the state and its institutions, their primary responsibility is to protect, serve and protect the rights of citizens, having a better understanding of the relationship between state and society, with power being legitimised by the consent and support of the population: police forces are an integral part of the community and work for the common good.

Police ethics first received international attention in 1979, when the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe started work on the proposal for Recommendation No. 858 and Resolution No. 690, which laid the foundations for common police legislation for Member States: the emphasis at that time was not only on internal organisation and functioning, but also on the ethical principles and ethical standards which should govern the conduct and service of each member.

This vision of the Parliamentary Assembly did not become a legal instrument as the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe did not support the resolution (due to the divisions that still existed among European states).

Interest in the field of policing gained new momentum after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rapprochement of Eastern European states to more democratic principles: to raise the quality of police training, the Council of Europe promoted seminars, learning programmes, reports, exchanges of experience.

A number of actions were also launched, which did not directly target, but had an impact on, the police forces. In fact, the Council of Europe created:

- in 1989, the "European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment" to examine the treatment of imprisoned persons;

- in 1990, the European Commission for Democracy through Law, to facilitate the preparation and adoption of constitutional charters in line with European constitutional standards;

- in 1999, the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), to fight corruption. Worth particular mention is the following:

a. Recommendation No. R(2000)10: enshrines the need for codes of conduct for all public officials;

b. guidelines adopted for assessments, including the adoption of effective codes of conduct for civil servants;

c. promotion of a Criminal Law Convention and a Convention on Corruption.

The Council of Europe encouraged the debate for a common policy in the field of police ethics in a democratic society. In 1998, the "Committee of Experts on Police Ethics and Public Order Problems" (PC-PO) was set up to study a pan-European ethical framework for the police: it was as a result that the scarcity of international instruments applicable to police forces and the ongoing reorganisation in many European states due to the democratic impulses described above became apparent. The PC-PO concluded its work with Recommendation No. R (2001)10 "European Code of Police Ethics", adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 19/09/2001.

The European Code of Police Ethics represents a milestone in police ethics, helping to shape and renew the relationship between the operators of the different institutions and the citizens, for whom it can become a model. Indeed, this Code:

- having been structured around the universal recognition of human rights, it enshrines that the responsibility for policing is elevated to a supranational level, with full participation of each state;

- shifts the main focus of policing from the use of public force for the maintenance of order and security to an instrument at the service of the community;

- establishes the separation of police forces from judicial bodies and the power relations between them;

- expresses the need for police forces to have a code of conduct that defines the legitimacy of their actions, their impartiality and respect for the community of which they are members.

3. THE GENDARMERIE NATIONALE'S ETHICAL FRAMEWORK

The ethos of the Gendarmerie has progressively evolved to adapt to contemporary challenges. As part of a historical excursus, it is possible to understand the current foundations of these ethics, based on the timeless values of loyalty, integrity and service dedication.

The origins of the Gendarmerie date back to the Middle Ages. During the Hundred Years' War, marechaussées were created to discipline soldiers off the battlefield. In 1536, the scope of responsibility was extended to control over the civilian population to maintain order in the countryside and protect the king's lands. In 1778, all the marechaussées were united into a single corps which was given jurisdiction over the entire national territory. Formed over centuries of political instability and conflict, the Gendarmerie has inherited an ethos of dedication to the common good and respect for legitimate authority.

With the advent of the French Revolution, the marechaussée underwent a comprehensive change in its role and mission: in 1791 it became one of the pillars of the Republic, the Gendarmerie Nationale, with responsibility for maintaining public order and defending the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity. These periods were important in establishing its ethics, emphasising political neutrality and impartiality.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Gendarmerie faced the challenges of modernising society and crime, demonstrating courage during the world wars and decolonisation. After the Second World War, it played a key role in the reconstruction and defence of democratic values, being recognised for its discipline, courage and responsibility, as well as for its ethics structured around honesty, impartiality and respect for human rights.

Gendarmerie ethics are based on constitutional principles, laws, regulations and international treaties that outline the national regulatory framework within which gendarmes operate:

1. Constitution: establishes the fundamental principles of the state, including those relating to public security, the protection of fundamental rights and the organisation of police forces.

2. Law 2009-971 of 03/08/2009: dedicated in its entirety to the Gendarmerie, introducing amendments to the Criminal Code, Criminal Procedural Code, Defence Code and Internal Security Code.

3. Defence Code: established in Order 2004-1374 of 20/12/2004, it regulates the organisation and functioning of the Armed Forces (including the Gendarmerie), establishing the duties, powers and responsibilities of the gendarmes, as well as the disciplinary rules to be observed.

4. Internal Security Code: established in Order 2012-351 of 12/03/2012, it regulates the activities of all police forces and bodies; setting out provisions in relation to the prevention and suppression of crime, the maintenance of public order, the protection of persons and property.

5. Professional ethics: the Gendarmerie has its own code of ethics, which came into force on 01/01/2014 on the basis of the provisions of the Internal Security Code: it sets out the ethical and moral principles that gendarmes must follow in their daily work and emphasises the importance of loyalty, integrity, professionalism and humanity in their actions.

6. Laws and regulations: in addition to the above-mentioned codes, there are numerous laws and regulations that specifically regulate the work of the Gendarmerie in various contexts (such as counter-terrorism, road safety, environmental protection, etc.).

Firstly, the legal ethics of the Gendarmerie are rooted in the Constitution, especially in the fundamental principles of the Fifth Republic. In particular, these principles establish the duty of the state to preserve security and ensure the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms. In addition, the Constitution defines the role of the different armed forces, including the Gendarmerie, in providing responsibility for the nation and territorial security for the state. Finally, the Constitution also establishes the framework of legality within which different democratic institutions operate, emphasising the role of the rule of law and the observance of democratic principles. The Charter is therefore the legal pillar of the Gendarmerie's ethics and essentially guides the actions of gendarmes to work in the public interest and protect democracy.

Law 2009-971 of 03/08/2009 legally subjected the Gendarmerie to the Ministry of the Interior, while protecting its military status, keeping it under Defence. Worth mention are a number of its sources:

- Law of 28 Germinal An VI (17/04/1798) on the organisation of the Gendarmerie, which contains the following principles:

a) Title VIII Police and Discipline: Possibility for gendarmes to appear in court and be punished for offences committed in the line of duty, establishment of a disciplinary register concerning the conduct and punishment of military personnel, establishment of a Disciplinary Council, ban on drunkenness, ban on being a trader or holding other employment;

b) Title X Means of protection of the freedom of citizens against unlawful and arbitrary detention;

c) Title XVII General provisions with rules on the use of force and the use of weapons;

- Decree of 20/05/1903 "Regulation on the organisation and service of the Gendarmerie" (repealed by the law of 2009), Title V "General duties and rights of the Gendarmerie in the execution of the service" of which contains articles on prevarication, abuse of power, illegal arrests, detentions, seizures.

The Defence Code provides an essential legal framework for the ethics of the Gendarmerie, setting out the duties, powers and responsibilities of gendarmes within the Armed Forces and defining their role in protecting the nation. The code underlines the need for gendarmes to act in accordance with democratic principles and the fundamental rights of citizens, ensuring the protection of national security and respect for the rule of law. In fact, it defines the internal discipline and standards of conduct for gendarmes, ensuring that the laws and regulations governing their work are complied with. The ethics of the Gendarmerie are based on the moral obligation to defend the nation and its values, respecting the ethical and legal principles governing the actions of the Armed Forces.

The Internal Security Code is an essential legal pillar for the ethics of the Gendarmerie. Regulating the activities of the police forces, it sets out the rules and procedures to ensure the prevention and suppression of crime, the maintenance of public order, the protection of persons and property. It also determines the powers and limits of the gendarmes' actions, ensuring that they act with respect for the fundamental rights of citizens and democratic principles.

The Code of Ethics establishes moral and behavioural principles of the gendarmes' service, with a view to guaranteeing that the fundamental rights of citizens are respected and the corresponding lawfulness of actions: they shall act in all circumstances with loyalty, integrity, professionalism, impartiality and humanity, with respect for the principles of hierarchy, obedience and public service. In addition, the code promotes solidarity, mutual respect and collaboration between gendarmes, based on ethical principles. Its principles are reaffirmed in the twenty-two articles of the Gendarme Charter.

Today, the ethics of the Gendarmerie are structured around four core pillars: Loyalty, Integrity, Professionalism, Humanity.

Loyalty is a deep and unconditional commitment to the Republic and its people. Gendarmes take an oath of allegiance to the nation, pledging to defend its sovereignty and respect its fundamental values, such as liberty, equality and fraternity. This bond is the basis for all the actions of the gendarmes, who are committed to scrupulously respecting the law and defending democratic institutions without exception, acting with determination and dedication to protect citizens and ensure the security of society: their mission is to serve the public interest, renouncing any form of compromise or deviation from their moral obligation. The gendarmes work together as a cohesive team, on the understanding that they are part of a single entity that pursues the stability and well-being of the country.

Integrity represents an unwavering commitment to honesty, transparency and moral consistency. They are expected to maintain exemplary behaviour in all situations, acting with rectitude and respecting the highest ethical standards. This value is crucial for public confidence and the credibility of the institution: it implies the absolute rejection of corruption and embezzlement. Gendarmes must resist the temptations posed by the abuse of power or disloyal conduct, always remaining faithful to justice and fairness. This commitment extends to all professional activities, both operational and in administrative procedures, requiring full transparency: in this way the Gendarmerie maintains its integrity, reinforces community trust and ensures fair and impartial decision-making.

Professionalism is a constant commitment to operational excellence, technical competence and respect for professional standards: the gendarme must demonstrate a high level of readiness and competence in all aspects of their work. This takes the form of ongoing, up-to-date training, thus enabling the acquisition of the knowledge and skills necessary to adapt to the changing demands of the evolving social and criminal context. Professionalism is also demonstrated by efficient resource management, optimisation of operational processes and the ability to change and make timely decisions. It involves respecting ethical standards, care for all people, acting with empathy, respect and understanding.

Humanity reflects a commitment to the humane, respectful treatment of all persons with whom the gendarmes interact. It recognises the need to focus on individual needs and circumstances, both in an ordinary context and in a conflict environment. It manifests itself in non-discriminatory attitudes towards all members of society regardless of their origin, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or social status. It is imperative that gendarmes interact with each individual person with dignity and respect; preserve their fundamental rights, develop relationships with the community by actively listening to needs, problems, empathetic dialogue. These are the foundations of building trust and creating real connections with the community. Linked to this, it is necessary to speak of humanity in the most literal sense: to approach sensitive and emergency situations with compassion and solidarity, especially when communicating with victims and witnesses of crime. The aim is to reduce trauma and generate the widest possible participation in justice.

In conclusion, the ethics of the Gendarmerie are structured around a long tradition of service and sacrifice, enriched by universal values of justice, respect and solidarity. These principles continue to guide the work of the gendarmes in their daily commitment to ensure the security and well-being of society.

4. THE ETHICAL FRAMEWORK AND THE ETHICS COMMITTEE OF THE CARABINIERI.

The ethos of the Carabinieri is built on a solid historical foundation rooted in the principles of justice, legality and service to the community. To understand the current foundations of this ethic, it is necessary to examine the historical journey that has shaped the identity and values of the Corps over the centuries.

At the start of the Restoration in 1814, immediately following the overthrow of Napoleon, King Victor Emmanuel I of Savoy wanted to overturn all the reforms that had resulted from the French revolutionary and then Napoleonic period: however, in response to the significant social instability and the precariousness of public security resulting from the geostrategic upheavals of the time, the King decided to create a police force, expressing his admiration for the French Gendarmerie, known for its efficiency and loyalty in performing the dual role of civil and military police. In the same year, the foundations were laid for a new elite corps, whose function of ensuring internal stability was considered so important that it came after the protection of the Sovereign.

The issue of the Royal Patents on 13/06/1814 saw the birth of the Carabinieri, and the reorganisation of the entire public order and security sector, which would see this Corps as its operational arm: the text contains the fundamental features that continue to characterise the force to this day. The term carabiniere derives from the name of a particularly accurate firearm, which was used by units with a higher level of training, as they were highly mobile and proactive: characteristics that were observed from the outset in the Corps, which often had to operate in isolated services far from command centres.

With the primary task of guaranteeing public order and institutional security, the Carabinieri have experienced many historical stages, faced challenges and social changes, but always remaining faithful to the fundamental values and principles of their mission.

During the Unification of Italy, the Carabinieri played a crucial role in defending national unity and fighting foreign forces of oppression. Its loyalty to its country and its commitment to freedom and independence helped forge a reputation of clear courage and unconditional dedication. The same happened during the Second World War, both during the Fascist period and during the German occupation: proof of this is both the large number of members of the Corps who were deported to Germany precisely because of their total loyalty to the King and the full confidence placed in them by the population, and the number of carabinieri who voluntarily sacrificed themselves as substitutes for citizens who were to be subjected to summary executions.

With the establishment of the Republic, the Carabinieri became an irreplaceable pillar of democratic institutions, vowing to be faithful defenders of equality, justice and human rights. The adoption of the 1948 Constitution guaranteed the Corps the duty to maintain order and security, as well as to uphold the law and respect the rights of citizens. In confronting social challenges, such as organised crime and terrorism, the Carabinieri demonstrated their loyalty to the defence of the community and social stability, guided by the values of integrity, responsibility and duty.

The ethos of the Corps, from its earliest official documents, is based on respect for law and justice to protect citizens' rights and democratic norms. The Carabinieri must act in accordance with the law, avoiding any abuse of power, with impartiality and transparency in their fight against crime. At the heart of its ethics is service to the community, demonstrating empathy, compassion and respect for human dignity. This dedication to the common good underpins the deep trust and relationship of mutual respect and affection with the people they serve.

The Carabinieri's ethical principles are enshrined in a variety of sources, reflecting both the regulatory context and the historical and professional identity of the institution. The main sources that set out its ethical principles include:

1. International treaties: Italy is party to treaties establishing norms and principles relating to human rights, the fight against transnational crime and international security cooperation.

2. Constitution: establishes the inalienable principles on which police action is based. It enshrines respect for human rights, legality and equality before the law, which are also core values for the ethos of the force.

3. Laws and regulations: there are specific laws and regulations which, in regulating the activities of the Carabinieri, reiterate these principles. Worth particular mention are the following:

- Legislative Decree No. 297 of 23/10/2000: reforms the Corps, defines and reiterates its tasks and functions, both in Italy and abroad;

- Code of Military Order, legislative decree No. 66 of 15/03/2010: regulates the organisation, functioning and tasks of the armed and defence forces; Book Four sets out the principles of military discipline;

- Decree of the President of the Republic No. 90 of 15/03/2010, Consolidated Text of the Regulatory Provisions of Military Order, which rationalises the organisation of the Armed Forces: Book Four identifies the principles of military discipline. Article 732 is worth particular note; following four paragraphs that apply to all the Armed Forces, there are two more specific paragraphs dedicated to the Carabinieri, reproduced in full:

In addition to the rules set out in the preceding paragraphs, Carabinieri personnel shall conduct themselves in accordance with the following additional duties:

a) maintain, even in their private life, serious and decent conduct;

b) observing the duties of their status, also in embarking upon relationships or friendships;

c) safeguarding serenity and good harmony within the department, also in the interest of the service;

d) maintain perfect and constant good harmony with other military personnel;

e) use polite manners with any citizen.

For Carabinieri staff, the following constitutes a serious disciplinary offence:

a) negligence and unjustified delay in the performance of duties related to the special powers that members of the Carabinieri Corps perform, in execution of orders, at the request of the authority or on their own initiative;

b) resort to anonymous writings;

c) make immoderate use of alcoholic substances or, in any case, narcotic drugs;

d) failure to repay amounts owed or contracting debts with persons who are morally or criminally unsuitable.

The discipline of the Carabinieri is therefore much stricter and covers not only the service but also the private life of its members.

4. The General Regulations: this internal document sets out the ethical principles, duties and responsibilities of all its members, as well as the rules of conduct of the service. A point of reference since the creation of the Corps, there have been several updates and the latest version, still in force today, dates back to 1963. The Prologue to the General Regulations deserves special mention for its function and specific nature. In fact, it contains the guidance notes of each Commandant General when the Regulations were issued, in which the fundamental features to be taken into the utmost consideration in translating the Regulations into daily practice were underlined. The current Preamble is divided into six paragraphs which, with the exception of the first (which is only an explanation of the Regulation), outline important values for all Carabinieri:

- the second paragraph sets out the levels of competence, identifying freedom of action (commensurate with rank and function) as a fundamental element for the performance of the service;

- the third celebrates the spirit of initiative, which is essential for any carabiniere, especially when isolated;

- the fourth stresses the importance of respect for duties, which must be demanded with "persevering energy and determination";

- the fifth emphasises personal responsibility, which cannot be separated from initiative and respect for duties: even in the absence of direction and control, each carabiniere must be irreproachable in their conduct out of a sense of responsibility;

- the sixth is the culmination of a series of regulations in which we can see ethical, leadership and personnel management principles: this paragraph emphasises that work must be carried out in pleasantly and in a serene climate of mutual understanding, which are indispensable when it comes to not punishing initiative and developing the companionship, comradeship and solidarity that form the cement of the organisation.

5. Tradition and historical identity: the Carabinieri's ethical principles are also influenced by its long history and tradition. Loyalty to the homeland, a sense of duty and dedication to public service are values that have deep roots in the history of the institution and continue to guide its work to this day. A number of books on ethics have been written over the years (some used as texts for study at Carabinieri schools), which have helped to shape the institution's ethical framework. In addition to the aforementioned Royal Patents and the Preamble to the Regulation, the following are worth note:

- "L'Art De Commander”, by André Gavet, published in 1945;

- "Galateo del Carabiniere - con gli avvertimenti per l'allievo Carabiniere", by G.C. Grossardi, published in 1879, reproduced by the Carabinieri Headquarters in 1973;

- "Prolegomeni sull'Etica nell'Arma dei Carabinieri" by Alessandro Gentile, whose second edition of 1995 is still in use;

- "Etica del Carabiniere" edited in 2017 by a working group of Officers at the Carabinieri Headquarters.

Also worth mention is the Commentary to the European Code of Police Ethics, produced in 2023, which makes a comparison with the legal and regulatory framework of the Carabinieri, explaining the content of the Code and showing the institution's adherence to it.

These sources combined constitute the regulatory and value framework that guides the professional ethics and daily work of the Corps, ensuring that it acts in accordance with the law, human rights and democratic principles. These principles are fully integrated in publication D-17 "Carabinieri Training Directive" approved on 03/02/2024 (repealing the previous directive), which regulates the teaching of ethics across all training schools of the Corps, both for initiation and advanced courses.

Thus, the fundamental ethical principles of the force can be identified as follows:

1. Loyalty: the Carabinieri demonstrate absolute loyalty to their oath, as well as a deep sense of loyalty to the Constitution, to democratic institutions and to Italian citizens. This value implies a total commitment to defending the interests and values of the society they serve, even at the risk of their own lives.

2. Initiative: a fundamental principle of the Corps that drives the Corps to be proactive and creative, taking on operational challenges and meeting the needs of the community. It persists in the awareness of competencies and responsibilities, in the desire to serve the public interest and the security of citizens, and in the ability to adjust quickly to new situations.

3. Legality: the Carabinieri are committed to acting within the law, ensuring that their actions comply with legal and constitutional principles. This principle underlines the importance of acting fairly and correctly, avoiding arbitrary behaviour or abuses of power, and obeying the law.

4. Discipline: a key element of the force’s ethos, which translates into strict compliance with established orders, rules and procedures. This principle ensures the effectiveness and efficiency of operational action, as well as respect for authority and hierarchy.

5. Responsibility: implies a sense of duty which is an overall moral and professional commitment that translates into service to the community and the fulfilment of institutional obligations. The Carabinieri are guided by a strong sense of responsibility in the exercise of their duties, constantly placing public interest at the centre of their actions.

With a view to continuous improvement and pursuant to the European legal framework, the force's Judicial Ethics Committee was created in 2022, a fundamental pillar to ensure that institutional work adheres to the highest ethical and legal principles. The establishment of the body demonstrates the commitment to promote an organisational culture characterised by lawfulness, integrity and respect for human rights. Its members, who are qualified experts in legal, ethical and social disciplines, were chosen on the basis of their expertise and impeccable reputation.

The Committee provides opinions and advice on ethical and legal issues related to operational and institutional activities. The body’s duty is to analyse the situations submitted, to examine their impact from different angles and from a multi-disciplinary approach, operating in a collaborative manner. In doing so, it assesses the ethical, legal and social implications.

Moreover, at a time when modern society is changing so rapidly, these issues are of the utmost importance and topicality. The Committee plays a crucial role in ensuring that the institution preserves its reputation and integrity: it promotes an organisational culture characterised by lawfulness and morality, helping to preserve the trust of the community and to strengthen the bond between the force and the citizens it serves.

In short, the Carabinieri ethos is based on a rich history of dedication to public service and the defence of democratic values. As part of its respect for lawfulness, justice and sense of duty, the Force continues to embody the highest professional standards in its daily efforts to ensure the safety and well-being of society. Page 7 of Etica del Carabiniere (details provided above) contains the following statement:

“The Carabiniere's Ethics remains an open work. But the project is clear and its foundations are solid.”

5. THE CODE OF CONDUCT FOR CIVIL GUARD PERSONNEL AND THE TEN GOLDEN RULES FOR THE GRUPO DE ACCION RAPIDA

The Spanish Civil Guard was founded in 1844, during the reign of Isabel II, in a period of profound political instability, internal conflicts (in particular, a number of local rebellions and the Carlist wars) and corruption, which contributed to fomenting discontent and poverty among the population, with the resulting detrimental effects on public order, especially in rural areas, where the phenomenon of banditry constituted a growing threat to the security and well-being of citizens: the force was created with the primary aim of responding to the need for security and public order throughout Spain. Before its creation, policing functions were fragmented amongst different local and regional organisations: excessive fragmentation and lack of coordination and organisation rendered these local organisations ineffective and incapable of effectively managing law and order at a national level.

Francisco Javier Girón y Ezpeleta, Duke of Ahumada, the first director of the Civil Guard, was the driving force behind the project to create a force with military discipline and civil police functions to maintain order throughout the country. Structured around an intelligent strategic conception, the Duke conceived Guardia Civil as an armed military corps, with a hierarchical disciplined structure and a strict ethical code of conduct. The aim was to ensure the stable presence of the Crown, effectively combat crime and protect citizens throughout the territory. The "Cartilla del Guardia Civil" is a manual of moral conduct in which an emphasis is placed on honour, integrity and discipline. The individual actions and the collective identity of the institution were structured around these virtues, which has survived to the present day.

The 20th century was marked by major ethical challenges, such as the Moroccan campaign and the advent of the First World War, which led to increased social and military tensions. These tensions were aggravated by the proclamation of the Spanish Republic, the Civil War and the rise of General Francisco Franco's regime. The aim of Guardia Civil was to maintain internal standards of conduct, despite possible political circumstances that could push them towards their suffocation[1].

Following the death of General Franco in 1975 and Spain's subsequent transition to democracy under a parliamentary monarchy, a process of internal transformation of the Corps began, revitalising its ethical framework in accordance with international laws on human rights and respect for public freedoms: this was a period of important internal reforms, which also affected the courses imparted, with the ethical and legal training updated to align Guardia Civil with the new democratic values, while at the same time the Corps faced new and no less serious problems, including those linked to Basque pro-independence terrorism.

Today, Guardia Civil is an organisation that reflects a full balance between its historical traditions and the needs of a modern, vibrant and plural society, capable of facing modern challenges that also have supranational repercussions, such as immigration management, international security and the fight against confessional terrorism, which require a delicate balance between operational efficiency and respect for public freedoms, with an emphasis on transparency, accountability and respect for human rights.

The ethical principles of Guardia Civil are reflected in a variety of sources, which highlight the dual nature of a military corps fulfilling civilian police functions, reflecting both the regulatory context and the historical and professional identity of the institution. The main sources include:

- International treaties: Spain is party to treaties that form part of the internal order (as indicated in the Constitution, Title III Chapter III Articles 93 to 96) and therefore form part of the legislative and ethical framework of the Corps as well.

- Spanish Constitution (BOE-A-1978-40003 and amendments): Article 104 states that all security forces, including Guardia Civil, must respect fundamental rights and public freedoms.

- Organic Law 2/1986 on Security Forces and Corps: Created under Article 104 of the Constitution, it defines the basic principles and general by-laws of the Spanish security forces, at national, regional and local levels. In its preamble, it mentions the Council of Europe Declaration and the UN Resolution on the code of ethics for members of the police, stressing respect for the Constitution, service to the community, proper use of resources, subordination and accountability in police work. Furthermore, it expresses the mission of protecting rights and guaranteeing citizen security, with specific mentions of the Corps (Articles 13, 14 and 15 of Title II, Chapter III).

- Organic Law 11/2007, regulating the rights and duties of members of Guardia Civil: this legislation was created to maintain the Corps' adherence to an ever-changing society. Title I regulates the fundamental rights of members as citizens with public liberties and Title II recalls the duties of the Corps (respect for the Constitution, principles of hierarchy and discipline, legitimate use of force, neutrality and impartiality, and confidentiality), with it being more important to define rights than duties, as the latter are already well established.

- Law 29/2014, of 28 November, on the Civil Guard Personnel Regime: this regulation addresses in detail all the administrative aspects, as well as personnel management and training, that govern the professional life of a member of the Corps, from their incorporation to their discharge, taking the previous sources and Organic Law 12/2007 on the Disciplinary Regime as a frame of reference.

- Royal Decree 176/2022 establishing the Code of Conduct of Guardia Civil: this decree is a guide for Guardia Civil personnel, updating the ethical principles of the Charter. Its purpose is to formalise and update the principles of conduct, incorporating them into the Spanish legal system, respecting national and international standards and the human rights proclaimed by the Council of Europe and the United Nations.

The code of conduct is divided into three parts: the first six articles define the standard, then there are two titles with two chapters each, and a decalogue which sets out the indispensable elements to be constantly kept in mind. Title I sets out values and ethical standards, while Title II provides details of standards of behaviour and conduct during service.

It underlines the importance of respect for national and international laws, emphasising the personal and professional integrity of each member of the Corps, to uphold a high standard of honesty and morality in service and in their private life, thereby building and maintaining public trust.

Accountability is emphasised as a principle to prevent deviations, ensure transparency and assume the consequences of actions in order to maintain institutional integrity.

Political neutrality and impartiality once again feature as a cardinal principle in the new code of conduct: the need to treat all citizens fairly and impartially, regardless of their beliefs or orientations, including gender equality and respect for diversity.

- Royal Decree 96/2009 approving the Royal Orders for the Armed Forces: given the military nature of the Corps, the Orders are fully applicable in the performance of military duties and include ethical values already established for the Civil Guard and specific to all military personnel.

Considering that the Charter of Guardia Civil is a fundamental historical document which, beyond its legal value, establishes the ethical principles and guidelines of the Corps, setting moral and protocol standards, mention must be made of what appear to be the key fundamental principles, which were then taken up by the entire regulatory framework of the sector and which continue to have a major impact on the culture and ethics of Guardia Civil, still constituting the essence of each of its elements:

1. Honour: The concept of honour is central to the Charter and is considered a civil guard's most valuable asset. Honour, according to the Duke of Ahumada, transcends mere reputation; it is an intrinsic quality that should guide all actions, both in service and in the private sphere. This principle implies an uncompromising adherence to integrity, truthfulness and fairness.

2. Loyalty: The Charter emphasises loyalty to the Crown and to State institutions, which requires members of Guardia Civil to perform their duties with absolute dedication, complying with the law without allowing personal or external interests to influence their judgement or actions.

3. Responsibility: Each member of the Corps is required to exercise their duties with the utmost responsibility and seriousness; this includes the duty to protect citizens and their property, to maintain public order, to ensure that justice is administered fairly and impartially.

4. Respect for the law and human rights: Although the concept of human rights, as we know them today was not fully developed in the 19th century, the importance of respect for the law and the principles of justice was included in the Charter. Each civil guard is instructed to respect the law and to treat all citizens with dignity and respect at all times, avoiding abuses of power and unfair or harassing behaviour.

5. Discipline and sobriety: Discipline is considered essential for maintaining order within the Corps and for the effective performance of assigned tasks. Sobriety, understood both in terms of moderate behaviour and correctness in the use of uniform and personal cleanliness and neatness, is essential, as a good image contributes to public consideration and authority.

6. Benevolent spirit: the indications provided by the Duke of Ahumada convert the Civil Guard into a true benefactor, who is seen by those in need as a divine blessing.

As part of a study on the ten golden rules of Guardia Civil, it is only fair to mention the Ten Golden Rules of the Rapid Action Group, a special anti-terrorist unit created for the fight against ETA, known for its high level of preparation and rapid response capacity: although it has no official character, given its content and roots in the department, it is considered worthy of consideration.

These ten rules outline the basic principles of the unit's professional behaviour and ethics. Analysing them, it is possible to glimpse the same ethical principles of Guardia Civil, revisited in a more operational key, typical of special forces and elite units used to intervene in high-risk situations.

Below, an attempt has been made to identify the essence of each point:

1. Holistic training: The first principle underlines the importance of training that combines moral, intellectual and physical aspects, recognising that the effectiveness of a RAG member depends on holistic training.

2. Operational readiness: Maintaining constant operational efficiency of weapons and equipment reflects the high readiness required of RAG members, ready to respond quickly to any threat at any time.

3. Determination: This point is an invitation to face difficulties with perseverance and calm determination.

4. Resilience: Difficulties are part of service and, as such, should be accepted calmly and in the knowledge that they can be overcome in the line of duty.

5. Surveillance and resilience: While on duty, it is a priority to remain constantly focussed and concentrated on the duty at hand.

6. Solidarity: camaraderie, the knowledge that we can rely on each other no matter what happens, cements unity and allows us to face any situation with determination.

7. Honesty: Moral integrity is paramount, with an explicit call to avoid lying, which is considered despicable.

8. Exemplary conduct: A neat uniform and even-handedness with the public promote authority and a strong public image, echoing some of the Corps' own ethical traits.

9. Courage and sacrifice: Recognises the value of risk and sacrifice, valuing those who strive unreservedly to achieve success.

10. Trust and Expectations: The last point addresses full trust in leaders and the legitimate expectations of professionalism, which are essential and indispensable for the success of the mission and the cohesion of the group.

The Golden Rules, taking up values for which Guardia Civil is already known, complements these by highlighting the importance of an even stricter code of ethics in a context of high tension and danger, establishing ethical and moral pillars that guide the education, training and conduct of GAR operations.

The evolution of the Civil Guard's ethos illustrates its adaptation to the changing needs of society and to fundamental democratic principles. This historical journey has not been without its difficulties, but it demonstrates a constant commitment to improvement and adaptability, with an eye firmly placed on respect for the law and human rights, and offering valuable lessons on how institutions can evolve and respond to change, while maintaining a core of fundamental ethical values, easily assimilated on a day-to-day basis.

6. AGILITY AND KAIZEN: A VALUABLE REFERENCE FOR CITIZENS?

The analysis of the legal and regulatory frameworks of the Gendarmerie, the Carabinieri and Guardia Civil revealed many similarities in the ethical principles and values of the three forces, as set out in various instruments, based on their different historical and cultural legacies, as well as their adherence to the laws in force in each country.

In light of this, the question arose as to whether different ways of preparing the instrument corresponded to different levels of usability and knowledge of its content. A simple anonymous questionnaire was therefore sent to senior officers of the three forces (in the ranks of Colonel, Lieutenant Colonel, Commander), holding positions in central agencies and national educational institutions or departments of an international rank, who were asked to answer the following questions:

1. Where are the ethical principles of the force set out?

2. Are there specific force documents setting out the ethical principles of the force?

3. What are the fundamental principles of the force’s ethics?

The answers highlighted three different situations: strong knowledge of sources and principles, partial knowledge or knowledge with errors, lack of knowledge.

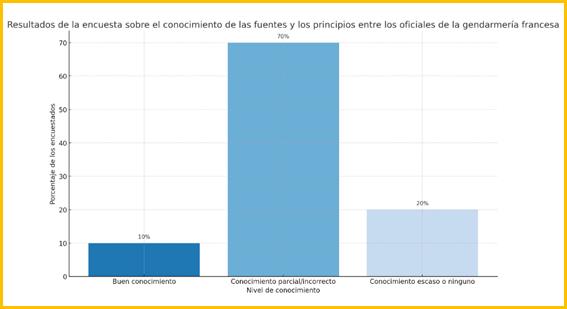

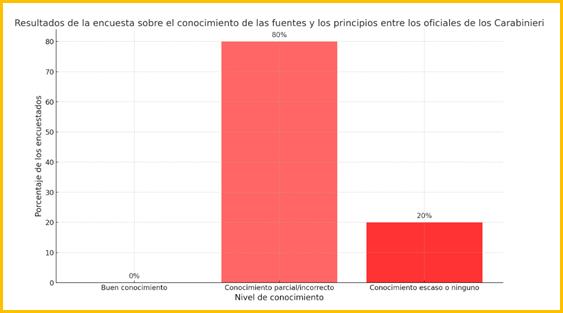

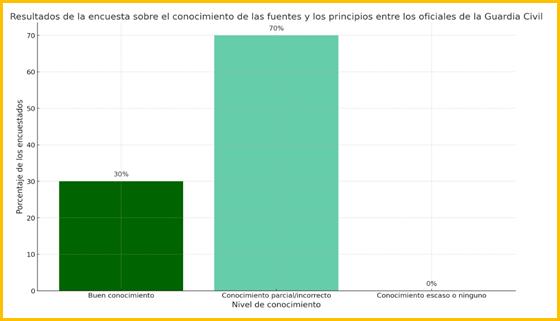

The following figures, one for each of the three forces, attempt to transpose the data collected through the above-mentioned questionnaires in visual form:

Figure

1. Prepared internally.

Figure

1. Prepared internally.

A sample of ten officers of the Gendarmerie Nationale demonstrated that:

- 10% of respondents have a strong knowledge of sources and principles (dark blue bar): all sources (general and Gendarmerie-specific) and most of the ethical principles were cited;

- 70% have partial/incorrect knowledge (medium blue bar): sources were cited generically, or only the main Gendarmerie sources were cited, and only a few fundamental principles were stated.

-

20% have little/no knowledge (light blue

bar): despite the fact that they knew there was an ethical framework, there was

an evident inability to cite sources and ethical principles.

20% have little/no knowledge (light blue

bar): despite the fact that they knew there was an ethical framework, there was

an evident inability to cite sources and ethical principles.

Figure 2. Prepared internally.

From a sample of ten Carabinieri officers, it was found that:

- None of the respondents had a good knowledge of sources and ethical principles;

- 80% have partial/incorrect knowledge (medium red bar): sources were cited generically or only Carabinieri-specific sources were cited or documents that are not sources were cited; few fundamental principles were stated.

-

20% have little/none knowledge (dark red

bar): there was an inability to cite sources and ethical principles.

20% have little/none knowledge (dark red

bar): there was an inability to cite sources and ethical principles.

Figure 3. Prepared internally.

In a sample of ten Civil Guard officers, it was found that:

- 30% of respondents have strong knowledge of sources and principles (dark green bar): all sources (general and Guardia Civil specific) and most of the ethical principles were cited;

- 70% have partial/incorrect knowledge (medium green bar): only those specific to Guardia Civil were mentioned; some fundamental principles were stated.

- None of the interviewees have little knowledge.

Comparing the results of the questionnaires and the ethical framework of the three forces as it is currently configured, it can be seen that where it is structured in the form of ten golden rules, the level of knowledge is higher. It is then considered possible to identify a number of key characteristics that a code of ethics must have in order to be a valid instrument for guiding the professional conduct of those it addresses:

1. Clarity: the required standards and behaviours should be formulated in a simple and straightforward manner to facilitate understanding and avoid ambiguity. It would be advantageous to exemplify this in specific professional situations.

2. Current: the code must be up to date, in the double sense of adhering both to the professional challenges of modernity and to the changing sensitivities of society.

3. Agility: a code of ethics should be an easily consultable instrument and bring together all fundamental principles.

4. Ethical support: the code of ethics should be a valid ethical support, allowing doubts to be dispelled by reading it and acting as a clarifying support for those experiencing ethical dilemmas.

There are immutable values that are already ingrained and definitively acquired, taken for granted in Western society: examples are respect for human dignity and human rights, which is also reflected in the codes of ethics of the forces in question. Other values can be traced to having a clear mission and a well-defined ethical framework that constitutes a secure point of reference and should become an acquired habit.

In this context, it is important to cite the first report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL), active since 1994 in the UK to advise the Prime Minister on ethical issues in public life. Page 17 of the report, known as the Nolan Report - 1995, states:

“Public sector workers cannot be expected to internalise a culture of public service unless they are told what is expected of them and the message is systematically reinforced”.

This passage is symptomatic of two aspects:

- clearly and unequivocally, it is necessary to tell and explain to public employees what is required of them, what they must do, what are the insurmountable ethical stakes that those called upon to perform a public service must know and respect;

- ethical principles and moral values must be repeated systematically, to stratify them and convert them into a staunch conviction.

Codes of conduct should be structured in a streamlined and user-friendly manner, not as convoluted or scattered documents. This not only facilitates teaching and outreach to new recruits, but also facilitates consultation for those with ethical concerns.

Another element to be taken into consideration for a code to be effective is that it should be up to date and in line with evolving cultural and social realities, without forgetting the ethical challenges posed by the pressures of new technologies. It should therefore be reviewed periodically both to reflect changes in the specific field and to incorporate the most up-to-date standards, as well as to promote new ethical understandings and interpretations.

From this perspective, the Japanese concept of Kaizen (continuous improvement), seems appropriate: in essence, it is a philosophy or practice focused on the constant improvement of people, business processes and efficiency. Originally conceived to be applied in the context of craft and industrial manufacturing, Kaizen emphasises a collective approach to improvement, involving all levels of an organisation, from the top down, starting with the improvement of each individual: this concept has been transferred to many other non-economic social spheres, such as education and health, highlighting its almost universal applicability.

The basic principle of Kaizen is that no day should go by without some improvement: starting with small daily incremental changes, significant improvements in quality, efficiency and productivity are eventually achieved in a positive growth movement that involves both the individual and the entire organisation.

Continuous improvement is a habit of mind that serves as a cornerstone for a consistently strong and effective organisation. In the context of a police force, three main pillars can be identified:

- the individual: the fundamental cell of the organisation, it is a priority for each member to be aware of the possibilities for personal development, which involves a thorough understanding of their roles and the ethical context governing their responsibilities. Self-improvement begins with knowledge and continues with the full internalisation of institutional values: this process not only increases the individual's effectiveness in the performance of their duties, but also reinforces fellowship, a sense of belonging and identity within the organisation. In this way, each member of the institution becomes both a guardian of shared values and an active promoter of these principles in the day-to-day performance of the service;

- the Institution: performs a fundamental guiding role and is responsible for providing the basis on which ethical values must be cultivated and maintained. This implies sparing no efforts to disseminate and clarify institutional ethical principles and to establish a fair and rigorous system of sanctions. This serves the dual purpose of discouraging unethical behaviour and reinforcing a culture of integrity and accountability amongst members of the organisation;

- lifelong learning: constant learning, updating and reflection are essential in a rapidly changing world with a wide variety of stimuli. Integrating ethics into training, including promotion courses, emphasises the importance of morality throughout the individual's career. Training should not be an isolated act, rather a leitmotif to promote the highest ethical standards throughout the organisation and in the professional development of each individual.

Continuous improvement is a never-ending virtuous cycle that requires a constant and coordinated commitment between individuals, the institution as a whole and its training structures: only through a holistic approach that places ethics at the centre, through continuous learning, can an organisation aspire to achieve and maintain excellence while safeguarding its value identity.

The ethical codes governing the work of the forces, which must be public and easily understandable, not only facilitate their continuous review and improvement, but also serve as a tangible example to society. The transparency and visibility of ethical principles such as integrity, impartiality and respect for the law and inviolable rights in daily service and in special operations conducted by these forces against any person, encourage citizens to assume these behaviours in their own conduct. This fosters a broader culture of lawfulness and mutual respect, which is vital for the preservation of the social fabric and also for its improvement. By observing these rules in action, citizens can find inspiration to incorporate similar practices into their daily interactions, both private and work-related, thus strengthening the pillars of an equitable, just and caring community.

7. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS AND PERSPECTIVES.

The comparative study of the codes of ethics of three of the most important law enforcement agencies in Europe reveals that the effectiveness of these documents is crucially based on their agility. This feature, defined by the ease of use and clear understanding of the contents, is essential for the ethical values to be not only learned, but deeply internalised by the members of these forces and applied in everyday life.

Codes of ethics, as guiding documents for professional conduct, must be drafted in a way that is directly applicable to the challenges and daily situations faced by these professionals in a very specific public sector. This implies that they should use clear and accessible language, avoiding unnecessary technicalities that may hinder understanding. Simplicity in structure and clarity in concrete examples illustrating appropriate and inappropriate behaviour are also vital for these codes to be truly functional and practical in day-to-day operations.

The agility of codes is also reflected in their ability to constantly adapt and update themselves in the face of social, cultural and, not least, technological change. While maintaining its value essence over time, an effective code of ethics does not remain static, rather it evolves with the society it serves, ensuring that its contents remain relevant and respectful of the rights and freedoms at the time.

In addition, the accessibility of these codes not only benefits those who directly apply them, but also has a powerful impact on the wider society where these forces are at work. When citizens observe that the security forces act consistently within a clear, consistent and respected ethical framework, a higher level of trust and respect for these institutions is generated. This, in turn, fosters greater community collaboration, which is essential for crime prevention and resolution.

Moreover, as they are public, understandable and constantly improving, these codes serve as models of ethical conduct for the general public. The visibility of principles such as integrity, impartiality and respect for the law in the daily actions of the forces encourages citizens to emulate these behaviours in their own lives, thus promoting a culture of lawfulness and mutual respect.

In conclusion, the ethical codes of Gendarmerie Nationale, Carabinieri and Guardia Civil demonstrate that agility (understood as accessibility, clarity and relevance) and continuous improvement are fundamental to their effectiveness. These codes not only guide law enforcement in their daily undertakings, but also act as ethical beacons for society, reinforcing the bond of trust and cooperation between citizens and those tasked with protecting them, with the ultimate goal of achieving a better society.

8. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Charter of the Gendarmerie of the Gendarmerie Nationale 2010 (Francie).

Commentary to the European Code of Police Ethics (internal publication Arma dei Carabinieri) 2023.

Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL) - First Report - Volume 1 - Chairman Lord Nolan (May 1995)

Carabinieri Training Directive (internal publication Arma de Carabinieri) 2024.

Gavet A. (1945). L’Art de Commander

Gentile A. (1995) Laurus Robuffo - second edition. Prolegómenos sobre la Ética en el Arma de Carabinieri.

Grossardi G.C. (1879) Galateo del Carabiniere - con gli avvertimenti per l'allievo Carabiniere, reproduced by the Carabinieri Headquarters in 1973.

Working group of six Carabinieri Headquarters Officers (2017) L'Armadillo Editore. Etica del Carabiniere.

Preston P. (2011), Cles (TN), Oscar. La guerra civile spagnola.

Reglamiento del Arma de Carabinieri (internal publication Arma de Carabinieri) 1963.

9. REGULATION

Code of Ethics of the National Police and the Gendarmerie Nationale. Codified in Book IV, Title 3, Chapter 4 of the Internal Security Code - 12/03/2012 (France).

Internal Security Code. Order 2012-351 of 12/03/2012 (France)

Spanish Constitution (Constitución Española). BOE-A-1978-40003 (Spain).

Constitution of the Italian Republic (Italy).

Constitution of the Fifth French Republic 4 October 1958 (France).

Decision No CDPC/109/120698 of the European Committee on Crime Problems;

Decree of 20 May 1903 regulating the organisation and service of the Gendarmerie Nationale (France).

Legislative Decree No. 297 of 23 October 2000. Reform of the Carabinieri. Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 248 of 23 October 2000 - Supplemento Ordinario No. 173 (Italy).

Legislative Decree No. 66 of 15 March 2010. Code of Military Order (COM).

Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 106 of 8 May 2010 - Supplemento Ordinario No. 84 (Italy).

Decree of the President of the Italian Republic No. 90 of 15 March 2010. Consolidated Text of the Regulatory Provisions of Military Order (TUOM).

Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 140 of 18 June 2010 - Supplemento Ordinario No. 131 (Italy).

Law of 28 Germinal Year VI (17 April 1798) on the organisation of the Gendarmerie Nationale (France).

Law 2009-971 of 3 August 2009 on the Gendarmerie Nationale (France).

Organic Law 2/1986, of 13 March, on the Security Forces. BOE-A-1986-6859 (Spain).

Organic Law 11/2007, of 22 October, regulating the rights and duties of members of Guardia Civil. BOE-A-2007-18391 (Spain).

Law 29/2014, of 28 November, on the Personnel Regime of Guardia Civil.

BOE-A-2014-12408 (Spain).

Organic Law 12/2007, of 22 October, on the Disciplinary Regime. BOE-A-2007-18392 (Spain).

Order 2004-1374 of 20 December 2004. Code of Defence (France).

Royal Patents of 13 June 1814 of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

Royal Decree 96/2009 of 6 February 2009, approving the Royal Ordinances for the armed forces. BOE-A-2009-2074 (Spain).

Royal Decree 176/2022 of 4 March establishing the Code of Conduct of the Civil Guard. BOE-A-2022-3477 (Spain).

Council of Europe Recommendation No R (2000)10: Codes of Conduct for Public Officials - 11 May 2000

Recommendation No R (2001)10 of 19 September 2001 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe;

Resolution No. 690 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe: Statement on the Police - 8 May 1979;

Resolution (97)24 of the Group of States against Corruption: adoption of the Twenty Guiding Principles for the fight against corruption - November 1997.